The law finally catches up with Tom and Gramby Hanley after murder of Culinary boss

Part 4: Tom’s confessions and Gramby’s Senate testimony fill some gaps in father-son crime saga

Listen to this article.

Read the series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Last of four parts.

Authorities located Tom and Gramby Hanley on the lam in a Phoenix apartment. In late March 1977, both agreed to give up once police issued warrants for their arrest. The state warrants came in mid-April, followed by federal warrants, on kidnapping and murder charges. However, the Hanleys reneged and failed to surrender.

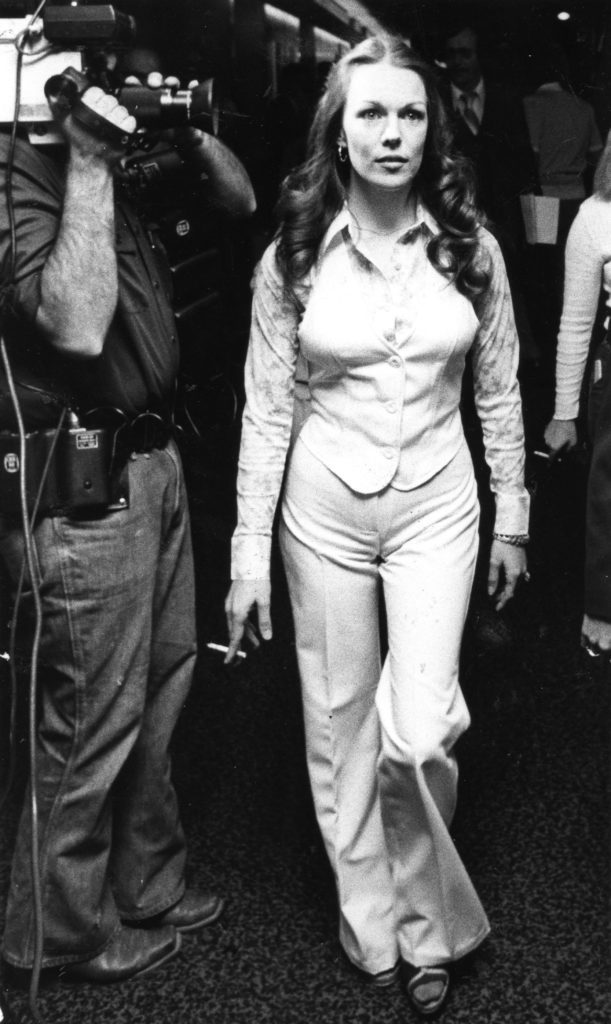

A grand jury in Las Vegas indicted Tom and his 21-year-old presumed wife, Wendy, on charges of receiving stolen property. Robert Peoples, a paroled convicted murderer and former prison cellmate of Gramby’s who became a family friend, informed police that Wendy unknowingly led him to places, including next to Tom’s mobile home in Pahrump, 60 miles west of Las Vegas, where Bramlet’s stolen jewelry, boots, underwear and socks were buried.

Peoples was working as an investigator for Hanley’s legal defense team. He contacted police when he suspected the Hanleys wanted him to commit a crime by disposing of evidence, likely sending him back to prison. Wendy, if she were Hanley’s wife, might not be able to testify against him. However, while Tom and Wendy obtained a marriage license, there was no record of an actual wedding ceremony. She never did testify. That summer, police arrested her on a murder charge. She had some of Bramlet’s jewelry in her possession. The D.A.’s office later reduced the charge to being an accessory to murder.

On April 29, 1977, FBI agents nabbed Tom and Gramby after spotting them sitting in a car next to a residential building in Phoenix. A federal judge in Arizona set their bail at $1 million each and ordered them held until Nevada authorities could take them in. Tom waived extradition. Gramby fought it.

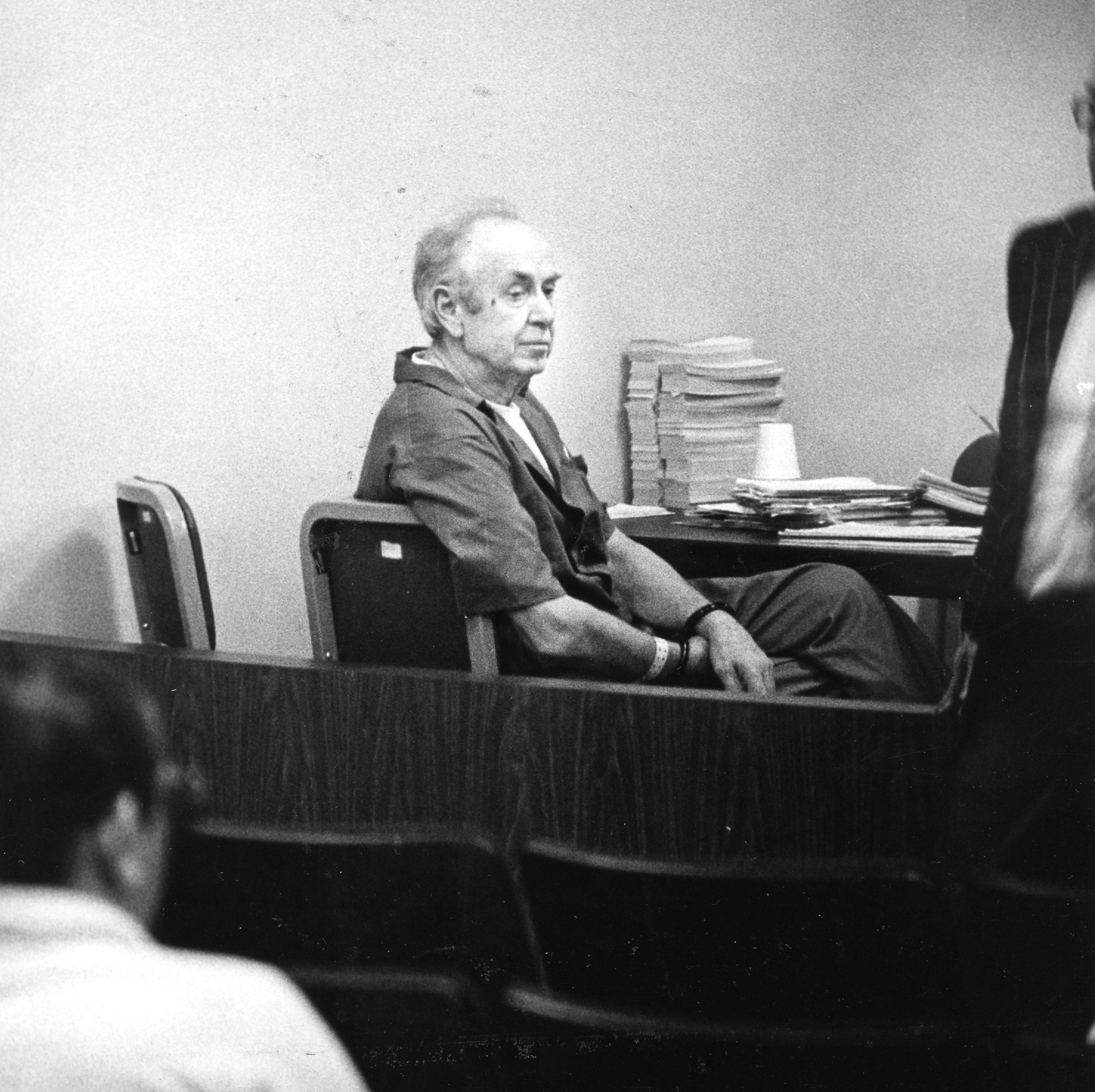

In May, back from a flight to Las Vegas, Tom spoke to reporters. In handcuffs, he said he remained in Phoenix for two months “trying to transact real estate deals” and build his criminal defense. Tom felt persecuted by the press and police, naming the same reasons when charged with murdering Alsup in 1966 – to kill his campaign for the casino dealers union. He took a firm stance, insisting on his innocence, not only in Bramlet’s homicide, but in the restaurant and casino bombings and conspiracies.

“I never had any animosity towards Al Bramlet,” he said. “He was one of the best friends I ever had.”

In jail, unable to raise a $250,000 bond, he consented to an interview with the North Las Vegas Valley Times. Tom declared he had an airtight alibi and could call a bunch of witnesses to back him. He suggested Vaughn made false statements in bitterness over a wage quarrel at Tom’s air conditioning company. He swore he had no motive to kill Bramlet, who he said sought his advice during the 1976 Strip hotel strike.

Bramlet murder case

In June 1977, at a preliminary hearing, prosecutors argued they had enough evidence to bind Tom and Gramby over for trial. Vaughn, granted immunity for testifying, described the two defendants’ complicity in the kidnap-murder and how he helped them bury the body. He said he watched Tom Hanley shoot Bramlet.

Peoples then took the stand and went further, providing an alleged motive for Tom to kill Bramlet – because he would not support Tom’s second try at organizing casino employees. In a conversation, Hanley told the ex-con that he needed the Culinary’s participation in the union drive and Bramlet had to be eliminated in favor of someone who would support it. Tom told him he wanted Bramlet’s jewelry transferred to Reno or Lake Tahoe, where once located it would discredit statements by police and Vaughn about the murder.

Beyond the jewelry, Peoples said Hanley also intended to transfer Bramlet’s body to the Reno-Tahoe area and induce a news reporter to write about its discovery there. As a rationale, he testified, Tom said unnamed union officials “back East” were unhappy with Bramlet and would support Tom eliminating him. Tom also stated that Bramlet had turned soft after the supper club bombings and might blab to police about them, Peoples said.

“Bramlet would have to go because Bramlet was weak and Bramlet had been shaky because of the bombing situations,” Peoples said. “Bramlet was weak and giving in to the clubs.”

Prosecutors produced damaging physical evidence from a cardboard box found in Phoenix containing a sports jacket and plaid pants. Barbara Bramlet, the victim’s widow, testified the clothes were indeed Al’s. Prosecution witness U.E. Wilson, a longtime friend of Tom’s, stated that Hanley asked him in April, while he and Gramby lived at Wilson’s residence, to stow the box for him.

The court ruled that Tom be tried for murder. In late September, a judge ordered Gramby bound as well. Gramby appealed to the Nevada Supreme Court. He said prosecutors violated his constitutional rights by illegally admitting evidence acquired after intimidating Peoples into becoming a secret informant and furnishing testimony against Gramby. The high court turned him down. Gramby’s lawyer should have filed the case earlier in the lower district court, the justices ruled.

In January 1978, prosecutors tried to consolidate the two defendants’ cases into one to save tax dollars, but a judge decided legal complexities would be too much for a single jury to handle. Tom’s lawyers filed motions for a change of venue outside of Nevada and to dismiss the charges. Evidence Peoples helped collect, they said, was illegally obtained, such as the jewelry and clothes Bramlet had on when he vanished that February. Turning Peoples, their former investigator, into a prosecution witness was enough to have the case dismissed, the lawyers said. Their motions failed to move the court.

At the end of April, Tom and Gramby went to the news media again, this time promising “bombshell” revelations that top-level Culinary officials in Chicago hired them to kill Bramlet, and they would name names. Behind the scenes, the Hanleys and their lawyers spoke to state prosecutors about a plea deal – agreeing to life sentences without parole – as long they did their time in a federal prison, not Nevada’s state system, where they believed they might be killed. Prosecutors allowed them to do their time in U.S. custody and join the federal Witness Protection Program in prison for extra security.

Tom and Gramby confess

Whatever the pair hoped to accomplish, there was no “bombshell.” On March 2, 1978, they changed their not guilty pleas in the kidnap-murder to guilty, confessed to the dirty deeds and admitted there was no additional suspect. They also pledged to aid federal law enforcement in the prosecution of unsolved criminal cases, i.e., the supper club bombings. Investigators brought up the Coulthard bombing, but Tom and Gramby, likely weary of yet more turmoil, declined to go there. The government consented to drop some charges that might have led to additional life sentences.

“There was nobody that discussed any killing of Mr. Bramlet at any time,” Tom told the judge as part of the plea agreement. “There was no such contract on Mr. Bramlet whatsoever.”

“I shot Mr. Bramlet,” he said. “I was drunk, but I did shoot him … I shot him three times … I may have shot him four.”

Hanley said after he, Gramby and Vaughn kidnapped Bramlet from the airport, they gagged him and put him in handcuffs. Once they reached the remote area, they had him exit the vehicle. Hanley said he wanted to bring Bramlet back to Las Vegas and that Gramby offered to drive. However, he claimed Vaughn objected, saying they would “all be in jail” if they released Bramlet. Hanley said that’s when he shot Bramlet. Tom also offered to take a lie detector test to deny his personal involvement in the 1960s murders of Alsup and Bass.

In the interim, Wendy, bailed out of jail, pleaded guilty to a gross misdemeanor count of conspiracy to pervert justice and received one year of probation.

Tom was sentenced first, on April 25, 1978, and then Gramby, in a separate courtroom. They both received sentences of life in prison without the possibility of parole. But before the pronouncement, father and son tried to pull another maneuver. They asked to withdraw their guilty pleas. Tom alleged the government bribed witnesses and suborned perjury. The judge refused.

District Judge Michael Wendell described Tom as “a shrewd, calculating and dangerous man. I think you are a danger to society.”

Tom testifies in bombing trial

Next was the trial in federal court. The Hanleys’ confessions in the supper club bombings in Las Vegas resulted in their indictments, handed down by a federal grand jury in April 1979. The co-defendants included Ben Schmoutey, Bramlet’s elected successor as secretary-treasurer of the Culinary Union, and Gramby’s men Howard Wilch, J.D. Northrup and brothers Rick and Harry Blasey. Tom and Gramby latched onto agreements with prosecutors to plead guilty in exchange for five-year concurrent prison terms and testimony before the grand jury about the bombings. Gramby admitted his responsibility in the David’s Place and two Alpine Village bombings and the unsuccessful ones at Starboard Tack and Village Pub.

Grand jurors, after considering the case secretly for two years, charged Schmoutey with racketeering, conspiracy, embezzling Culinary funds, arson and attempted arson of buildings and perjury in grand jury testimony.

Most significantly, the jury also charged Schmoutey with conspiring with Bramlet to allocate Culinary money to purchase bomb materials and to hire Gramby and other people to plant the explosives.

The federal trial produced some new information, and surprises. Bramlet’s first labor-intimidation conspiracy took place earlier, in 1975 at the non-union Harvey’s Wagon Wheel. The jury panel alleged that Bramlet hired defendant Wilch to set a fire at the casino. Schmoutey and Wilch were charged with providing explosives used by Gramby to bomb David’s Place in 1976.

Before the federal trial in October 1979, in Las Vegas, U.S. District Judge Harry Claiborne, Tom’s former longtime lawyer, ruled that based on a psychiatric evaluation, Tom was competent enough to understand questions and testify under oath against Schmoutey and the co-defendants. Claiborne also turned back a defense motion to dismiss the indictments. Federal prosecutors touted Tom and Gramby as star witnesses in the case against the five defendants accused in the successful and unsuccessful bombings from 1975 to 1977.

On the witness stand in U.S. court, Tom threw yet another legal curve, stating that he did not tell the federal grand jury the right story – the one that resulted in the indictments. He had told the closed-door grand jury that Schmoutey agreed to pay Tom $10,000 to blow up David’s Place. But now at the trial, Hanley claimed to have misspoken; that he really meant only Bramlet conspired with him and made the payment. Then Tom and Gramby insisted that federal prosecutors broke their promises to them and so moved to retract their guilty pleas to conspiracy allegations. The judge declined the request.

Prosecutors had presumed Hanley would detail in court what he told the grand jury, implicating Schmoutey in Bramlet’s murder. Schmoutey, Hanley had said, told him that Bramlet must be “snuffed out” because he might agree to expose Schmoutey and others in the bombings.

Something was wrong with Tom this time. He testified over several days, but in a rambling, contradictory and confused manner. He claimed deafness and asked lawyers to repeat many questions. He looked haggard, as if he had aged years in only months. In reality, he was suffering from hepatitis.

Oscar Goodman, Schmoutey’s lawyer, objected, saying that it would be too difficult to cross-examine in light of Tom’s mental condition. Relying on Hanley’s testimony to build its case against the defendants was a “clever, diabolical scheme on the government’s part,” Goodman said.

Judge Claiborne replied that Tom and Gramby, in order to avoid Nevada prison, appeared “ready to trade anything to get into a federal system, truthfully or not. And the government bought the wares they were peddling. As I said earlier, in the final analysis of the case I think we will all find that the government was a victim, a patsy, of the Hanleys.”

Claiborne ultimately agreed that Tom’s testimony was too flawed and incompetent because of his hearing and other physical problems for defense attorneys to interpret – so much so that he ordered his entire trial testimony stricken from the court record. The prosecution had lost a star witness.

“The question now before the court is, is Hanley capable of understanding the questions and relating accurately the events?” the judge said. “I have come to the conclusion he was not. He testified he answered many questions he did not hear.”

Former Mafia boss Fratianno appears as witnesses

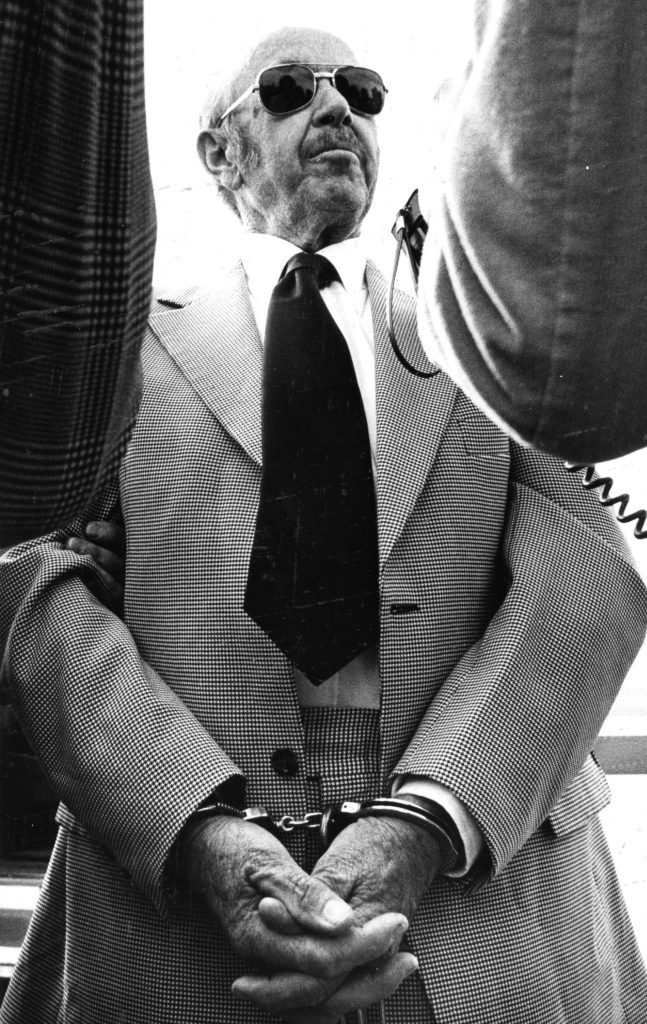

On November 8, it was not only Gramby’s turn, but a surprise prosecution witness – former Los Angeles crime boss and Mafia hit man turned federal informant and witness Aladena James “Jimmy the Weasel” Fratianno.

Gramby’s testimony, in another disappointment for the government, did not directly connect Schmoutey to the bombing conspiracies. He did finger defendants Wilch, Northrup and the Blasey brothers for being present or assisting him with the explosives. Rick Blasey, he said, was with him in 1975 while preparing the bomb that blew up at Harvey’s, and Rick and Wilch joined him later when Gramby went back to Alpine Village to check the fuse on the first bomb.

Fratianno, a paroled ex-con, in witness protection and complicit in multiple gangland murders since the 1940s, was the celebrity witness for the prosecution. However, his testimony made little impact. The former Mafia leader said he never knew Tom Hanley. He said that in 1976, at Fratianno’s seaside Northern California home, he met bombing defendant Harry Blasey, who told him “he was working for (Tom) Hanley and they bombed Harvey’s Wagon Wheel for the Culinary Union.” Then, in 1977, he spoke with bombing defendant Rick Blasey, who mentioned that police were after Gramby in the Bramlet slaying.

Claiborne’s ruling striking Tom Hanley’s testimony sent the prosecution’s case into a tailspin. Goodman and lawyers for the co-defendants filed for directed verdicts of acquittals by the judge. On November 20, 1979, in a 20-page ruling, Claiborne did just that, dismissing charges against Schmoutey and all but one lesser defendant, J.D. Northrup, because Claiborne believed the key witness against him – Northrup’s ex-wife.

About the main defendant, Claiborne said the prosecution failed to provide evidence “which would tend to show that Schmoutey was aware of or involved in the bombing or burning of any establishments named in the indictment,” nor did they prove the labor leader guilty of embezzlement.

Tom Hanley dies, U.S. Senate probes Culinary’s parent union

Just three days later, on November 23, Tom Hanley died at age 62. He passed from natural causes in a sequestered section of a local hospital, where he stayed under an assumed name after his transfer from a federal prison in the Midwest while testifying in the Schmoutey case. At his death, he was still in witness protection. About 30 people attended his funeral. His family buried him in an unmarked grave at Woodlawn Cemetery in Las Vegas.

Gramby kept up his fight to withdraw his guilty plea. In March 1981, the Nevada Supreme Court rejected his argument that he did not understand what the legal penalties of his plea to first-degree murder would mean. One judge noted that Gramby admitted to the court that the victim Bramlet “was not going to be allowed to return to town” and then helped bury the corpse.

Nevada’s tremulous and violent labor climate attracted added interest in summer 1982, when the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations held hearings in Washington on allegations of financial corruption and ties to organized crime within parent union HERE and its locals in Atlantic City, Honolulu, Reno, San Diego, Oakland and San Jose. As for Las Vegas, the subcommittee focused on Bramlet and Schmoutey. After Bramlet’s death, Schmoutey allowed the administration of the Culinary’s health and welfare fund to merge with HERE, which Bramlet had blocked.

A subcommittee informant reported that Schmoutey had been “controlled” by Las Vegas-based Chicago Outfit enforcer Anthony Spilotro through Culinary president Mike Pisanello, and had hired as a Culinary organizer Steve Bluestein, a notorious Spilotro associate. In 1981, during Schmoutey’s run for reelection as secretary-treasurer, the Review-Journal took a photo of Spilotro associates Joseph Blasko, Joey Cusumano and Herbert Blitzstein smiling outside union headquarters, there to aid Schmoutey’s election campaign with rank and file members. Schmoutey nevertheless lost the contest to Jeff McColl. The Senate panel learned in 1984 that HERE head Edward Hanley maintained secret ties to Chicago Outfit leaders Joey Aiuppa and Tony Accardo and that HERE charged “outrageously excessive” costs to administer dental plans in Las Vegas and Atlantic City locals to furnish payments to organized crime.

Gramby tells his story to Senate investigators

The subcommittee brought Gramby to Washington to testify on the coordinated assaults on non-union businesses in Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe in the 1970s. Committee staffers interviewed him seven times previously.

Gramby told Senate investigators beforehand that this father Tom helped form Local 88 in the 1940s with the assistance of the Teamsters Union. Tom, he said, had been framed in the murder of James Hartley in a power struggle with the Sheet Metal Workers International and expelled. Tom brought him at a very young age to Los Angeles as an apprentice in union activities with Local 108. Gramby learned how to organize, form picket lines and invest union funds.

Upon his release from a two-year stretch in state prison for burglary in 1974, Gramby said his father had him meet Bramlet, who was organizing properties in Reno and Lake Tahoe. Bramlet gave him $1,500 and sent him to the Tahoe area to scout casinos to see if any were “feasible” as sites to use smoke and stink bombs to influence labor disputes. Gramby chose Harvey’s as an easy choice and Sahara-Tahoe as “feasible,” meaning of lower cost and less chance of getting caught.

Bramlet, he said, was “eager” to start and hired him to bomb Alpine Village in Las Vegas, Harvey’s and Sahara-Tahoe as soon as he could. Gramby’s approach was to do three bombings at once. In 1975, he “wired” the bombs at Alpine Village and Harvey’s and aborted the job at Sahara-Tahoe when security guards spotted him. After the bomb blew up at Harvey’s, he drove to Las Vegas to detonate the one at Alpine Village.

Bramlet had offered him $25,000 for each explosion. The labor leader only gave him $6,000 to $8,000 for the first and $8,000 to $9,000 for the second. He accepted the cash through his father, Tom, who told him the money for the Tahoe jobs came via a picketing fund in Reno controlled by Bramlet. The Culinary head also offered him $25,000 to bomb David’s Place, but Bramlet himself paid Gramby only $10,000, which Gramby claimed came from someone in New York.

Gramby collected $50,000 total for the Nevada bombings from 1975 to 1977, about half of it passing through Tom’s Oasis Air Conditioning Company, which had an $80,000 contract for work at the Culinary headquarters. Further, he said, Bramlet made illegal payments to Tom of up to $60,000.

In 1977, Bramlet hired him to bomb the Starboard Tack and Village Pub to panic the management into signing with the Culinary Union. Gramby stated the firebombs were not designed to blow up, only startle the club owners.

Gramby further stated he came up with the idea to confront Bramlet on February 24, 1977. With Tom and Vaughn, they abducted Bramlet in a vehicle, asked him about the $10,000 he owed and about providing another $25,000 Bramlet promised for bail if Gramby got arrested. Bramlet agreed and made some phone calls in a desert area outside Las Vegas.

While driving, Gramby said Tom also questioned Bramlet about the possibility that union vice president Ben Schmoutey had recorded phone conversations in Bramlet’s office without Bramlet’s knowledge in which Bramlet informed law enforcement officers about alleged loans by the Culinary to people at the Dunes Hotel.

Bramlet, Gramby stated, as a union pension fund trustee, loaned Dunes owner Morris Shenker $28 million to $30 million, from which Shenker kicked back $1 million to $1.5 million to Bramlet. Gramby heard that from Tom, who claimed to have seen $500,000 of it in cash at a ranch Bramlet owned in Needles, California, and that Bramlet was also awarded a “chalet” in Switzerland.

At the time of his death, Bramlet, according to Gramby, was liquidating his assets and planning to leave the United States out of concern over being caught in the bombings and a federal law enforcement investigation of the Shenker loans. Gramby, likely from Tom, also claimed Bramlet wanted to “sell out” the Culinary to Frank Fitzsimmons, head of the Teamsters Union.

Once transferred from prison to speak before the Senate subcommittee, Gramby sat behind an opaque glass wall with federal marshals at his side. But the paranoid personality trait he shared with his father reared its head. Gramby informed the committee he would not testify without assurances that none of it would be used against him in future parole or pardon hearings in Nevada. The senators told Gramby they had no legal jurisdiction to offer an immunity agreement, and so Gramby declined to testify further.

Gramby dies in prison, served 43 years

What exactly happened to Gramby Hanley? He became one of the many inmates in witness protection, with extra security measures, while serving their state sentences in a federal prison. In the 1980s, he described for a reporter for United Press International the artwork – pencil drawings, paintings and sculptures – and poetry he created to pass the lonely times. Some of his works received considerable attention – one of his poems was read at Stanford University and at the World Congress of Poets in Europe in 1982. One of Gramby’s sculptures was on display for several years in The Mob Museum. For his security, he never joined the general prison population, and the U.S. government periodically moved him to different facilities.

“Why did I do the bombing? For the money. I had just gone through a divorce. My life was in disarray. My dad came to me and told me if I wanted to make some money, someone needed some bombings done,” Gramby told the Chicago Tribune by telephone in 1984.

The Nevada Department of Corrections website lists Gramby, inmate number 13552, among those convicted in Nevada, transferred to “out of state confinement,” but now deceased. It does not say exactly when he died. The department lists his age as 83, although he turned 82 on September 15, 2021. The location of his body has not been released. He served 43 years.

If what is known publicly about the crimes committed by Tom and Gramby Hanley over four decades is bad enough, what remains hidden – perhaps forever – may be much worse.

Former Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department homicide detective David Hatch, in an interview for the 2012 KLAS Channel 8 documentary In the Company of Killers, said the Hanleys likely were responsible for a lot more than the seven murders police believe they committed, including some done at the request of organized crime figures.

“I think between here and Phoenix, Arizona, especially in the Phoenix area – they did stuff down there,” Hatch said. “I don’t think this is a third of the killings they did. I really don’t.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org