Father-son crime team tormented Las Vegas over four decades

Part 1: Tom and Gramby Hanley were linked to murders, labor scandals and bombings

Listen to this article.

Editor’s note: Las Vegas outlaws Tom and Gramby Hanley were never members of a traditional organized crime group, but the menacing tactics they used to corrupt labor unions, and the murders and bombings they planned and executed, drew heavily from the Mob handbook. For more than 30 years, the Hanleys made as many headlines in Las Vegas as Bugsy Siegel or Tony Spilotro ever did. This four-part series marks the first time an extensive history of the Hanleys has been compiled. And yet one has the uneasy feeling we have only scratched the surface . . .

Read the series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

First of four parts.

Two murdered men found buried in the desert outside Las Vegas – nearly a quarter-century apart – had a grisly connection. Thanks to poor burial jobs by their killers, passers-by discovered each body after seeing a hand emerging eerily from the grave. Both men were labor union officials, shot execution style.

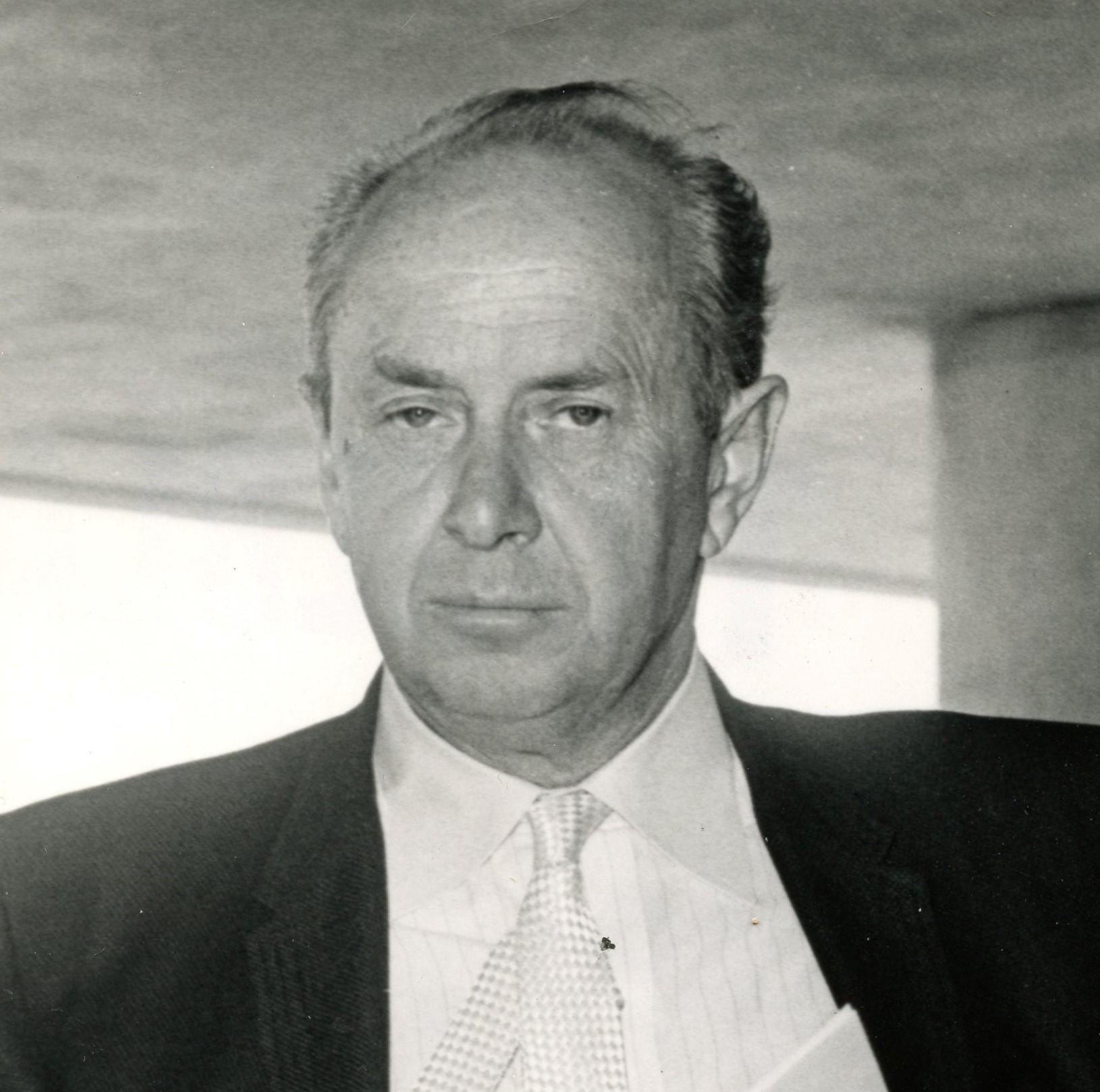

The victims, James Hartley and Elmer “Al” Bramlet, shared another connection – to a veteran labor figure with a violent past named Tom Hanley, a suspect in both killings. Hanley would escape justice on the first murder and receive a life sentence without parole for the second. In the interim, Hanley had enlisted his son, Andrew “Gramby” Hanley, as a fire bomber for hire and sociopathic partner in murder.

Tom and Gramby, an almost Teflon-coated, two-man crime group, brought calamity and disruption to Las Vegas for decades.

From 1975 to 1977, Gramby, with Tom as a co-conspirator, successfully bombed two non-union supper clubs in Las Vegas and a non-union casino at South Lake Tahoe, then tried and failed to bomb a second Tahoe casino and two other restaurants. Bramlet, as head of Culinary Union Local 226 and in control of Local 86 in Reno, paid Gramby, through Tom, to blast the businesses to scare them into signing union contracts.

But Bramlet angered the Hanleys when he declined to pay for the two bombs that didn’t go off. That led to the sensational kidnap-murder of Bramlet in 1977 and an investigation into the Chicago Mob’s infiltration of the Culinary, its parent the International Hotel and Restaurant Employees union (HERE) and HERE locals nationwide by the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in the early 1980s.

Gramby would tell subcommittee staff that in 1975, HERE sent money to pay for the Tahoe-area bombing to a Local 86 picket fund controlled by Bramlet. The subcommittee later reported that HERE wanted Bramlet to merge the Culinary’s huge health and welfare fund with the parent union’s so HERE could channel kickbacks to the Chicago Outfit. When Bramlet refused, Mob enforcers beat him up but didn’t kill him. The Senate panel heard testimony that HERE President Edward T. Hanley (no relation to Tom) and Chicago Outfit figures pressured Bramlet to give in before his death.

However, the subcommittee believed the Hanleys did away with Bramlet for their own reasons, despite Gramby’s opinion that someone paid Tom to kill him.

Legacy of labor violence, shakedowns

For nearly a quarter-century, Tom Hanley was a leading suspect in numerous slayings that remain unsolved today – Hartley, prosecution witness Alphonse Bass, potential witness Marvin Shumate, union officer Ralph Alsup and others, including former Las Vegas FBI agent William Coulthard.

Time after time, with prominent attorneys on his side, he beat charges of murder, attempted murder, kidnapping, robbery, conspiracy to commit robbery, extortion and assault. Tom also generated an extraordinary number of well-publicized controversies – arrests, jail stays, shootings, beatings, fights, alleged shakedowns, labor complaints, lost elections, picket lines, terminations and revenge-seeking lawsuits. His name made the headlines of hundreds of news stories in Nevada and California in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, sometimes several per week in Las Vegas, conceivably more than anyone else in town during that period.

Gramby, certainly his father’s son, also had many arrests to his name. Tom had coached Gramby, at times desperate for money to feed his heroin addiction, in pathological criminal acts for hire from inside their modest single-family home at 1621 Ogden Avenue, about 15 blocks east of downtown Las Vegas. They maintained a close relationship with Horseshoe casino man, ex-con and hoodlum Benny Binion, who wielded considerable political influence over the Clark County Sheriff’s Department.

Thomas Burke Hanley’s infamy in Las Vegas began in the late 1940s. Born in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1916, he moved to Las Vegas around 1940 and found work at the Basic Magnesium plant that manufactured magnesium metal into an alloy of aluminum for war munitions and airplane parts, vital to the U.S. military during World War II. After the plant closed in 1944, he helped found and rose to lead the American Federation of Labor Sheet Metal Workers Union, Las Vegas Local 88.

His proclivity for brazen violence materialized in 1948, when he was charged in the assault of a sheet metal worker at the union office downtown. In court, Hanley professed self-defense against the victim, and he was backed by two union-connected witnesses, including Local 88 business agent Hartley. Coulthard, former assistant city attorney and ex-FBI agent, testified that Hanley admitted in open court to beating the victim. The case attracted a lot of local newspaper coverage, but the judge ruled Hanley innocent, one of many times he would beat the legal system.

Tom’s labor career took off in the late 1940s. While with Local 88, he was elevated to secretary of the Clark County Building and Construction Trades Council. He advanced even further in 1951, when the Sheet Metal Workers Union parent, the AFL International, appointed him regional manager of its locals in Southern California, Nevada and Arizona. He moved to the International’s Los Angeles office, frequently traveling back to Las Vegas. At one point, some labor leaders viewed Hanley as a good candidate for International president.

However, Hanley’s criminal impulses made him unfit to be a legitimate labor leader. His newfound power emboldened his ambition, greed and willingness to resort to threats and beatings.

From 1952 to 1953, sheet metal workers were crucial to Cold War-era defense contractors fulfilling profitable guided missile, aircraft and other government projects in Southern California and Nevada. The workers also were important for builders of sprawling new subdivisions in the Southwest. But some sheet metal and plumbing contractors reported that Hanley and his union agents engaged in “shakedowns,” extorting them to pay cash to avoid work stoppages and picket lines at construction sites. Those sites included Las Vegas Strip hotels, Nellis Air Force Base and the Lake Mead military ammunition dump. Hanley’s handpicked motley crew of union officials included ex-cons willing to strong-arm and commit violence. News reports claimed demands from his extortion ring might have amounted to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In one case in 1953, four building contractors fought back. They sued Hanley’s Local 88 for $1.6 million in lost revenue, saying the union illegally halted contracted work on housing projects in Clark County. The local, they said, sent nine sheet metal workers to a construction firm’s office, where they threatened to harm its employees and destroy its property. Local 88 business agent Hartley, a close Hanley crony, warned he would “bankrupt” the company, they alleged. Weeks later, Local 88 agreed to halt the wildcat strike and return to work.

Hanley’s arrogance continued to swell in his International job. In Los Angeles, he ordered his favored union pals – such as a recent Nevada prison parolee named Ralph Alsup – to assist in a forced takeover of the large Southern California AFL Sheet Metal Workers Local 108. This plan, incredibly, even included an interstate contract murder (never completed) of a recalcitrant top union executive in Washington, D.C.

The murder of James Hartley

Tom’s controlling personality reached a breaking point amid some bizarre events in Las Vegas and L.A. in early 1954. On March 13, a youth walking his dog in a semi-rural area southwest of Las Vegas noticed a human hand protruding from a shallow grave in the desert soil. Sheriff’s deputies identified the corpse as Hartley, the missing 32-year-old Local 88 business agent, shot in the forehead, his body poorly buried and exposed, possibly after high winds and digging by coyotes.

Hartley’s wife, Ruth, said her husband seemed distraught for weeks before his death. She last saw him February 19, and he phoned her from Los Angeles on February 23. Hanley had reportedly tried to remove Hartley as business agent. A few days before Hartley left Las Vegas, a neighbor saw two men attempting to force their way into his apartment. Hartley’s makeshift gravesite was close to a farm owned by Local 88 official Alsup, the former president of the Clark County Federation of Labor and vice president of the Nevada State Federation. Alsup was on parole after serving one year in the Carson City state prison for the 1949 shooting of an unarmed union painter in a labor dispute. Alsup was also appealing a six-month federal prison sentence for scheming with contractors to rig bids on a government project. For months, deputies could not locate Alsup for questioning about the Hartley murder.

Police in Los Angeles, not yet knowing the significance, on February 26 seized an abandoned briefcase found at the city’s international airport. It contained several thousand dollars in government bonds and a Beretta handgun. Meanwhile, on March 9, four days before Hartley’s body was found, L.A. cops impounded Hartley’s disabled 1953 Chrysler New Yorker from the parking lot of Local 108 at 208 W. Seventh Street. Someone apparently drove Hartley’s car hundreds of miles and left it there after the murder. Detectives lifted a palm print from the car’s body. Deputies in Las Vegas estimated Hartley died between February 26 and March 4.

Hanley, almost immediately eyed as a suspect, denied any part in the murder. Then on April 1, sheriff’s deputies took in Sheldon DeWitt Rich, 52, a veteran labor figure in Las Vegas whom Hanley had just appointed as a union trustee. Rich was an ex-felon who served terms in California’s San Quentin and Folsom prisons for armed robbery. Deputies soon considered Rich the main suspect in the homicide, but with a lack of hard evidence, could only hold him on a morals charge – cohabitating with a woman not his wife. Rich revealed little under questioning, telling deputies, “They took care of me, so I’ll take care of them.” His lawyer, Harry Claiborne, won his release on bail. Rich would soon loom large in the Hartley case.

Clark County sheriff’s and Los Angeles police detectives conducted a joint investigation into the killing. In L.A., police found some witnesses uncooperative, fearing they might end up like Hartley.

The ongoing mystery evolved into a national story and regularly made the front pages of Los Angeles and Las Vegas newspapers. The Las Vegas Review-Journal published features on Hartley’s funeral at Woodlawn cemetery, grieving pregnant wife and infant son. Police speculated that Hartley was slain to prevent him from revealing the extortion ring. The investigation also discovered shortages of funds at Local 88 – from $5,000 to $30,000 – and many business records were missing.

Hanley admitted to L.A. cops that the briefcase was his, that he meant to deliver the bonds to sheet metal union locals in Southern California, carried the gun for protection and misplaced the bag at the airport.

News of the Hartley murder, the contents of Hanley’s briefcase, and alleged financial improprieties at Local 88 soon reached Robert Byron, head of the Sheet Metal Workers International in Washington. Byron also heard about possible intimidation and shakedowns by Hanley’s people. The labor chief summoned Hanley to his office in D.C. At the end of March 1954, Byron fired Hanley and revoked his union membership, citing, vaguely, “improper handling of union matters in this area.” The International also axed the ex-con Alsup and a few of Hanley’s cohorts. Hanley appealed his firing, and the union set up a trial board to hold hearings on Byron’s charges. His termination didn’t stop him from hanging out at the Local 88 office. Members complained that he browbeat and pressured them to see things his way despite losing his membership.

In June, a three-member board of the International opened the trial in a meeting room of the Statler Hotel in Los Angeles. Defendants included Hanley and his appointees C.A. Nichols, John Fuller and Troy Nance. The union contended Hanley brought disrepute to the labor movement, failed to report extortion attempts by Locals 108 and 88, had associates with criminal records, discredited the union through the publicity of the Hartley murder case, caused more than $150,000 in litigation against the union, took $12,000 in excessive expenses that pushed the Sheet Metal Workers Local 371 into insolvency and conspired to force a contractor to hire Alsup on salary as a “labor relations man” to resolve disputes with Local 108. Hanley’s union sidekick Clem E. Vaughn served as his counsel.

The trial quickly turned into a circus, with Hanley constantly disrupting the hearings and loudly raising the same objections to the point that the board’s chairman, Moe Rosen, adjourned days later, intending to try the defendants in absentia. The board later found Hanley and his buddies guilty, formally expelling all of them from the union in July. Hanley and Fuller lost their appeals in court.

Hartley murder mystery deepens

Meanwhile, a strange event revived the Hartley murder case that month, all the way out in the nation’s capital. Rich, the ex-felon and Hanley-appointed union trustee, met with Byron in the labor leader’s D.C. office. The apparently slow-witted Rich admitted to being part of a scheme to assassinate Edward Carlough, secretary-treasurer of the International. Rich said that a union person from the West Coast had paid him $600 to “find a trigger man” to kill Carlough. But Rich offered to cancel the hit for a payment of $15,000 and a decent union job. Putting him off, Byron reported Rich to the D.C. police.

Officers stopped Rich in his car. In the trunk, they recovered a .22-caliber rifle. Police arrested him and his companion, John Georgacakis, a Las Vegas race book operator, on suspicion of murder conspiracy, and Rich for possessing a gun while an ex-felon. Prosecutors failed to convince a D.C. grand jury to indict Rich and Georgacakis for conspiracy to kill Carlough. But jurors did haul up Rich on the gun charge. While Rich served 90 days in jail, D.C. officers sent the rifle to Los Angeles police. Ballistics experts there soon identified it as a match to the partial slug taken from Hartley’s head.

Rich started talking, telling D.C. police that Hartley’s murder may have involved “an ousted Las Vegas union official.” Almost everyone knew that could mean Hanley or Alsup. Hanley had put the convicted armed robber Rich to work at the Lake Mead ammunition dump, a U.S. armed forces project east of Las Vegas, where contractors reported alleged shakedowns.

Las Vegas deputies linked the palm print on Hartley’s car to Rich. He confessed to switching the license plate of his car onto Hartley’s Chrysler before driving on the Los Angeles highway toward L.A. through the Yermo, California, agricultural checkpoint. Rich told the spot check attendant that his name was “DeWitt S. DeWitt,” Rich’s middle name repeated.

In September 1954, a U.S. House subcommittee meeting in Los Angeles heard testimony that Tom Hanley began mismanaging a $2 million union welfare fund back in 1950 and overcharged the fund for office administration by about $40,000 a year. Hanley also put in Fuller, with no experience in insurance, as welfare fund administrator for Local 108 in Los Angeles, overseeing an employer-paid account with reserves of $400,000. The panel heard testimony that employer trustees of the fund had no ability to vote on the spending of it, and Hanley, not a trustee, exercised total control of the fund during board meetings before his ouster.

In October, in yet another weird twist, Fuller, the expelled former union member, informed L.A. police about a letter he placed in a bank deposit box, detailing the plan by several Local 108 officers to take over the entire International. Fuller was scared stiff he’d be killed for knowing too much. He told his wife he received death threats and asked her to deliver the letter to police if he ended up missing.

Fuller admitted to going with Hanley to a Las Vegas sporting goods store where they traded Hanley’s .38-caliber pistol for the suspected murder weapon and Fuller signed the sales receipt. He then gave the rifle to Hanley. Left unexplained was how Rich got the gun. Fuller added he attended clandestine meetings that year with union members in Tucson and Barstow. In Tucson, they discussed “ways to take over the International and get Byron and Carlough,” but Fuller declined to take part. In Barstow, they told him Hartley was missing and tried to get him to call the dead man’s wife and lie that Hartley was fine and in Los Angeles. He declined to make the call.

Fuller also detailed Hanley’s four-year shakedown scheme and named suspects in a paid plot to “get Hartley out of town, but I didn’t know then he would wind up dead.” It was Rich, Fuller stated, who drove Hartley’s car to the Local 108 lot and came into the office to ask Fuller to help push it there when the battery died.

“Two different times I was supposed to be killed (but) I was able to find out about it in advance,” Fuller wrote in the letter, as reported in the Los Angeles Times. “And I have been told three different times that if I was ever arrested that I would get out on bond and then would be killed and the case would be solved. I am no angel, but I believe anything can be settled without murder. … Please don’t let my wife and daughter get hurt – that is all I ask!”

Fuller accepted 24-hour police protection in his L.A. area home before his testimony after someone made telephoned threats, including “the next guy will be buried hands down” and “we’ll use a post hole digger next time.”

A county grand jury in Las Vegas compelled Hanley, Rich, Alsup, Nance, Nichols and Georgacakis to appear for questioning in Hartley’s murder. All six were suspected of being part of the aborted drive to take over Local 108. Other witnesses included members of the L.A. police racket squad and a pair of sheet metal contractors. The jury heard the makings of a murder conspiracy and allegations of extortion and financial wrongdoings. Rich remained the chief murder suspect. The L.A. police probe uncovered a suspected plot to compel Byron to resign from the International and give the conspirators high-level positions in the parent union. Nichols, appealing a six-month jail sentence for assault, told a judge in L.A. of getting a note claiming a risk of death “if he talked.”

In November, the grand jury recalled Hanley and Alsup for further testimony. Word leaked to the media about links to at least three murder suspects. Investigators heard stories of disputes within Hanley’s union and a possible conspiracy to kill Hartley because of his knowledge of the shakedowns and money missing from union coffers.

Newspaper accounts told of sources claiming Fuller would “finger” Hartley’s killers and that Rich, Hanley and Alsup all faced indictment.

However, the Las Vegas grand jury, evidently working under a high bar for proof, determined there was not enough evidence to indict anyone in the murder. One factor may have been that the panel at the same time investigated and indicted Clark County Sheriff Glen Jones and a county commissioner on corruption charges.

Deputies resumed the Hartley investigation in early 1955, but did not find new evidence to file a winnable case. Hartley’s murder was never solved, at least by a court of law. Hanley’s likely co-conspirators in the crime, Alsup and Nance, kept quiet. It was the first of several murder plots that Hanley got away with – including that of Alsup himself more than a decade later.

Tom’s one-time wife, Wendy Mazaros, in her 2011 memoir Vegas Rag Doll, claimed Tom admitted he killed Hartley with Alsup’s help.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org