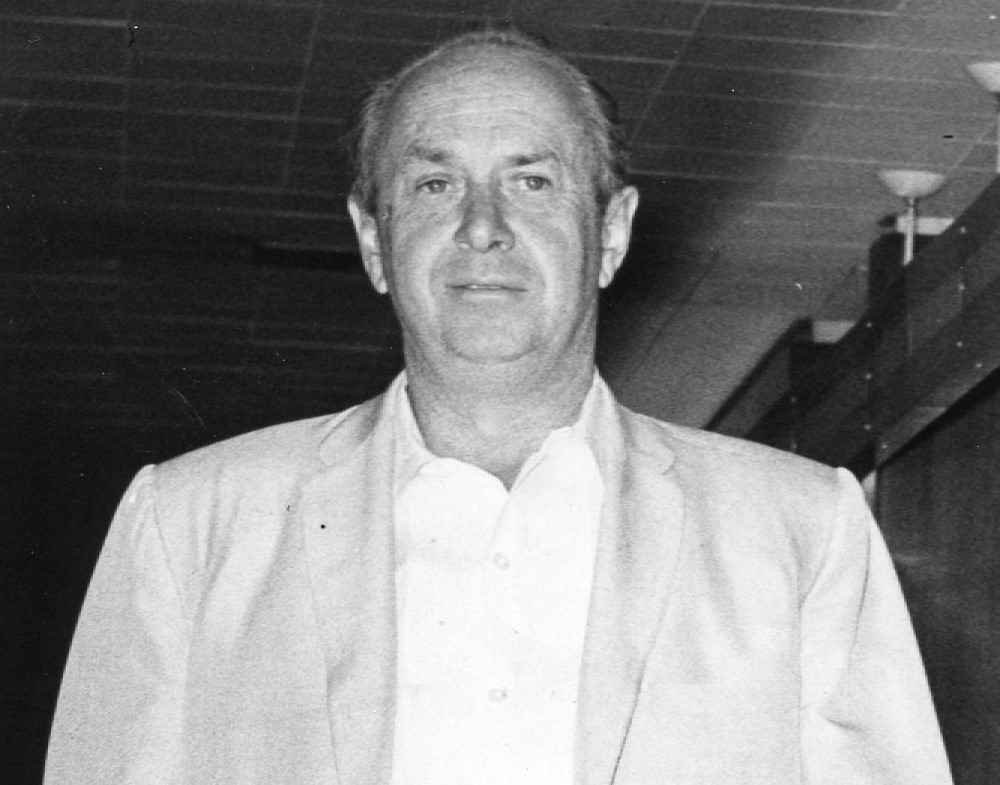

Labor corruption was centerpiece of Tom Hanley’s criminal aims

Part 2: Bold plan for casino workers union almost happened

Listen to this article.

Read the series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Second of four parts.

In 1955, the national AFL union (months before merging with the CIO) formally expelled Tom Hanley, Troy Nance and Ralph Alsup from the organization. Full of resentment, Hanley decided to start a new “independent” union of sheet metal workers, with him and Nance at the helm, to displace Las Vegas Local 88 for labor contracts. Contractors, however, rejected his overtures.

In July and August, despite his expulsion, Hanley again injected himself into Local 88’s affairs. He resumed verbal and physical intimidation of members, but with little effect. Clem Vaughn, business agent and Hanley’s front man at Local 88, called for a general strike. But it didn’t happen. Vaughn set up a picket line at the Stardust Hotel project on the Strip but withdrew it after about 10 minutes when workers walked right through it.

Deputies arrested Nance in the severe beating of Walter Vickers, a plumbing worker elected unanimously as the 100-member Local 88’s new business agent to replace Vaughn. The August 31, 1955, election followed a loud and violent union meeting attended by 15 sheriff’s deputies in plain clothes. Hanley stormed in and got into a fight in a hallway. Deputies booked him on disorderly conduct. Vickers immediately complained that Vaughn failed to return ledgers showing how the local spent its funds.

Hanley later phoned Vickers to meet him at a plumbing contractor’s office. When Vickers arrived, Hanley and Vaughn forced him against a doorway where Nance emerged and knocked Vickers unconscious. Amid reports of the fighting, county authorities placed Hanley’s two sons into temporary protective custody. A few weeks later, Edward Ralls, a Local 88 member who voted for Vickers, reported that Nance, in a car with several men, tailed him to a grocery store where Nance beat him up in the parking lot. A photo of Ralls with his bloodied face appeared in the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

Hanley’s proposal for a new sheet metal workers group went belly up. He shifted to his fallback plan of creating a union representing Las Vegas casino employees. He also filed multiple big-money lawsuits, essentially a form of shakedown. He lost a $300,000 suit against the International union, a $100,000 suit against a law firm in state court and a $300,000 defamation case in federal court. In 1958, with Vaughn as a co-plaintiff, he at first suffered defeat in a $225,000 wrongful termination suit against Byron and Carlough in Utah. On appeal, incredibly, a judge there found in their favor, ordering the union to pay them $20,000 each and restore their memberships. The International refused to settle and won on appeal in the Utah Supreme Court.

Hanley’s family problems

Meanwhile, members of Hanley’s dysfunctional family ran afoul of the law. In 1957, deputies booked 18-year-old Gramby in the assault of a 15-year-old boy, trespassing, kicking kids at a party and threatening them not to report it. In 1958, narcotics officers busted Gramby and five other youths on marijuana possession. Two weeks later, deputies arrested the teen for failing to appear in court on a driving without a license citation.

Things got worse for the Hanleys in the summer of 1960. Deputies arrived at the family’s Ogden Avenue home with a search warrant to look for jewelry stolen in early July from the Strip bungalow of singer Pearl Bailey while she performed at the Flamingo Hotel. Hanley punched a deputy, resisted arrest with the other and suffered a deep cut to his head. His family joined in the fracas. Deputies arrested his wife, Mary Lou, and sons, Gramby and Ned, on suspicion of resisting. Tom’s attorney, Harry Claiborne, helped all four beat the charges in December.

As it turned out, deputies came by the house to question Ralph Alsup’s 19-year-old son, Donald, about Bailey’s missing jewelry. Days earlier, Donald, who had been living at the Hanley residence, was arrested and bailed out with two other youths in the $15,000 theft.

Hanley’s other son, Ned Wayne, aged 18 in 1958, fared far worse. He was taken into custody in Las Vegas on a narcotics charge and contributing to the delinquency of a minor and arrested in New Mexico on suspicion of breaking and entering and possessing narcotics. In Las Vegas in May 1961, cops arrested him on another narcotics rap. Then in June, the 20-year-old Ned died at a hospital in San Diego of a drug overdose. U.S. Customs agents found him lying unconscious in a car with two young men, including Donald Alsup. The three had been to Mexico to buy heroin and Ned had used too much, agents suspected.

Hanley launches casino workers union

Tom Hanley began to chart a strategy to organize Las Vegas’ casino game dealers, change workers, slot machine technicians and other employees not covered by the Culinary and Bartenders unions. A casino union might interest thousands of dues-paying workers. Casino managers were typically strict in treating craps, roulette and blackjack dealers, who were closely monitored and verbally abused for dealing errors and if their tables lost to customers. The casinos often frowned on older dealers and punished their tip-seeking employees with shift assignments during slow times. Efforts to unionize casino employees in the late ’40s and ’50s failed. Dealers feared swift termination from their exacting supervisors.

Hanley, then 46 years old, unveiled his gaming union drive in 1963. He called it the American Federation of Casino and Gaming Employees (AFCGE).

Years later, in the 1980s, U.S. Senate investigators would contend that Hanley’s casino union movement was bogus and merely a ruse to extort thousands of dollars from Las Vegas casinos. Hanley’s reputed scam was to take aim at a casino, assign pickets to walk outside, demand a payment and, once received, remove the pickets.

On the surface at least, his pitch for the AFCGE in the 1960s hit a nerve with casino workers. Gaming employees were notoriously underpaid, made to work uncompensated overtime and subject to impulsive dismissal by managers. Hanley took over a dormant local of the Operating Engineers union, signed up as a nonprofit with the state of Nevada and began to recruit members. As self-appointed union chief, he said he would seek to represent the estimated 2,600 casino workers in Las Vegas and 2,400 in Reno.

Back then, most casino employees, depending on the property, collected an average wage of $22.50 per shift, with tips on top of that for experienced game dealers. Change providers, cashiers, slot technicians and new “break in” dealers received as low as $12 a day. Table game supervisors and box men got from $30 to $50. The casino industry, Hanley contended, had not raised gaming employee earnings since the early 1950s. Even into the 1960s, paternal (and sexist) Las Vegas and Clark County – by law – banned women as both casino dealers and bartenders. Hanley said he wanted to represent female dealers and pledged to support qualified Blacks, who faced discrimination in recently desegregated Las Vegas.

Hanley knew he would face stiff competition from the established, 10,000-member Culinary Local 226, the bargaining representative for non-gaming hotel and beverage workers. Headed by Bramlet, Local 226 opted to hold a drive of its own for casino employees. In June 1964, Hanley announced he had signed up about 800 game dealers to his AFCGE. Dealers liked his wage demand of $30 a day and protection from arbitrary firings. Hanley called for $47.50 a shift for supervisors and box men. He boasted that more than 51 percent of casino workers had signed pledge cards for his union, enough to be eligible for certification by the National Labor Relations Board to negotiate contracts with casino management.

Casino owners, well aware of Hanley’s expulsion from the Sheet Metal Workers Union, past arrests, intimidation tactics and reputation as a shakedown “hoodlum,” opposed his campaign. A casino union, they insisted, would subject their employees to federal labor laws and make it too hard to fire dishonest dealers.

The local press also groused about Hanley. Hanley’s widow, Wendy Mazaros, in her book, maintains that Hanley set the late 1963 fire that destroyed the offices of the Las Vegas Sun newspaper, published by Hank Greenspun, whom Tom hated for criticizing him. The official investigation concluded that overheating in the air-conditioning system triggered the fire.

Tom spared the Sun’s larger rival, the Review-Journal, which was no less disapproving. Its editorial board wrote in 1964 that “if the truth be known Mr. Hanley is far more interested in setting himself up with a plush job than he is in helping the casino dealers. … But it is our guess that in the end, Hanley will wind up sleeping with the hotel owners to an ever greater extent than Bramlet, if that’s possible.”

Predictably, Hanley responded aggressively to Local 226. In meetings attended by about 100 dealers, he charged casino management and the Culinary with conspiring to hinder his drive, and filed unfair labor practice complaints with the NLRB against four casinos and Bramlet. He sent telegrams to 12 casinos trumpeting his success in recruiting their workers. Owners of the Thunderbird and Dunes on the Strip denied his accusation that they had asked the Culinary to organize there without contacting his union.

Hanley seeks union elections at casinos

Hanley filed for organizing elections at the downtown Mint, Horseshoe, Pioneer, El Cortez, Golden Gate, California Club and Showboat casinos and later the New Frontier, Castaways, Hacienda and Tropicana on the Strip. The Mint would make history as the site of the first successful union election for gaming employees – seven slot mechanics voted 6-1 for Hanley’s union (it would be a rare victory). The Culinary arranged to be on the ballot with the AFCGE in future elections. Hanley then buried the hatchet. On June 22, at a mass meeting, he announced he would end his attacks on the union. “I have no personal fight with Bramlet or the Culinary workers,” he said.

In late July 1964, Hanley, the AFCGE’s newly elected business manager, declared that more than 1,600 casino dealers had signed authorization cards. The NLRB sent officers to Las Vegas to consider whether the U.S. government agency had jurisdiction in casinos and if the AFCGE or the Culinary should represent casino employees. The NLRB gave the AFCGE a boost by allowing it to bargain for dealers, change people, slot mechanics, cage cashiers and other casino staff at the Hacienda. This despite the fact that the NLRB said it would take about two months to decide whether to officially sanction the AFCGE.

When Hanley was suddenly hospitalized with a slipped disc, his momentum slowed and members lost energy as the NLRB’s process continued and casino owners stalled. Still, Hanley opened an office in Reno to organize elections at casinos there. Nevada Governor Grant Sawyer expressed overall support for collective bargaining by casino workers. But he angered Hanley by also saying that the NLRB should not take over the state’s role in controlling gaming by blocking licensed casinos from firing casino workers, or else the state might have to license all gaming employees. Hanley later conceded to owners, permitting automatic firing of cheating dealers within 24 hours after a fair hearing.

That September, Hanley ordered picket lines set up outside the New Frontier, Hacienda and California Club casinos due to contract impasses. With no progress, pickets were withdrawn except for at the California Club, where they remained for almost a year until the casino agreed to hold an employee election.

In November 1964, Gramby had more legal problems. He was charged with burglarizing a motorcycle shop and attempted grand larceny in the theft of trees from a nursery. Gramby bolted for Colorado – where he was born in 1939 – but was convicted of burglary anyway and extradited back to Las Vegas. In 1966, a judge sentenced him to one to 15 years in state prison. Freed for a while on appeal, he survived a drug overdose. He eventually served two years of his term.

In early January 1965, Hanley, still in pain from his aching back, was arrested after shooting two men in the leg when they came to his home and allegedly threatened him with a bayonet in a money dispute with a drug dealer. He was booked on possessing an unlicensed firearm. That March, deputies cuffed him after he recklessly fired his shotgun at a car parked in front of his house.

Days later, the NLRB formally recognized the AFCGE as a labor organization to represent casino workers, known as AFCGE Local 54. The NLRB ruled it had jurisdiction based on the federal interstate commerce act. Hanley laid ambitious plans to file about 50 unfair labor charges with the NLRB on behalf of about 150 workers and request a hearing about his $2 million civil suit against 16 casinos in Clark County, saying they had blacklisted him. In April, he filed for worker balloting at five casinos in Northern Nevada.

While accepted by the NLRB, Hanley’s AFCGE not only remained unaffiliated with the AFL-CIO and other major unions, it had yet to make it to the bargaining table to sign contracts. Interest in the AFCGE continued to wane, as working membership declined to less than 400. The NLRB permitted a vote at the Showboat and El Dorado casinos, giving about 200 employees the choice of the AFCGE, Culinary or no union representation. Hanley assigned long picket lines at the Mint and Golden Nugget hotels and insisted that the New Frontier and Hacienda had fired employees for union activities.

Finally, in early 1966, the AFCGE won three elections and prepared to sign contracts at the Bonanza Club and Jerry’s Nugget casinos in North Las Vegas and the Golden Gate in downtown Las Vegas. Hanley took aim at the Stardust, Sahara and Desert Inn on the Strip. But management at the Bonanza Club and Jerry’s Nugget later refused to sign deals. Hanley ordered a sit-down strike at Jerry’s Nugget. The casino hired non-union dealers to replace them. He then lost elections at the Mint, Lucky and Thunderbird casinos.

Alsup murdered, Hanley assaults IRS agent

Also that January, Ralph Alsup, the longtime Hanley associate and business agent for the plumber and pipefitters union local, was murdered, killed by a shotgun blast outside his home in southwest Las Vegas, not far from where Hartley’s body was found. Reporters speculated the homicide was part of a violent struggle against unionizing gaming employees.

Hanley’s antics still made front-page news unrelentingly in Las Vegas. His longtime predisposition to violence got him into hot water again in November 1966. Two agents of the Internal Revenue Service arrived at the AFCGE office on Seventh Street one afternoon to serve a summons to Glen Herron, Hanley’s main organizer. The IRS was investigating tax returns Herron prepared for Tom and Mary Lou Hanley from 1963 to 1965. Herron refused service outside, and an enraged Hanley pushed and later slugged an agent, who drew his gun and told Hanley he was under arrest. The agent also arrested Herron. Hanley’s labor lawyer, Albert Dreyer, was injured trying to arbitrate. Federal authorities charged Hanley and Herron with felony assault and interfering with the IRS, and another organizer, Vivian Brooks, with interfering.

The next day, IRS agents, U.S. marshals and sheriff’s deputies raided the office with a warrant to search for a pistol Hanley kept in a desk drawer. One agent said the day before, Brooks opened the drawer, revealing the gun to the agent. Hanley, the agent said, ordered her to close and lock it. Hanley, Herron and Brooks won release on bail. Hanley professed his innocence.

A federal judge sent the case to a grand jury, which indicted all three defendants on the accusations. Meanwhile, owners of the Pioneer, California Club and Bonanza casinos filed actions in state court and with the NLRB to force the AFCGE to stop picketing their properties. The AFCGE lost to the California Club and Bonanza but continued to picket the Pioneer.

Casino unions in election showdown

While Hanley awaited trial in the assault of the IRS agent in 1967, a new opponent, the Office and Technical Workers Union Local 29, announced its intent to pursue authorization by the AFL-CIO for a gaming workers union, having signed about 800 casino employees seeking insurance plans and better wages. Local 29’s leader, in an allusion to Hanley’s tactics, stated that he would not engage in “wildcat picketing, power plays and legal maneuvers” that have “done untold harm to the Nevada image, the gaming industry and the cause of respectable and responsible unionism.” Unlike Hanley, Local 29 would charge no dues or fees without signed contracts.

Another proposed union, the Seafarers International’s United Casino Employees, entered the fray, as did Bramlet, whose Culinary started Casino Employees Local 7. Bramlet obtained contracts at two casinos to represent change people and cashiers. Hanley tried and failed to merge AFCGE with Bramlet’s Local 7. Then the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers expressed interest in representing slot machine mechanics.

The showdown for Hanley, Bramlet and Paul Hill, president of the 85,000-member Seafarers International, came to an election at the Dunes Hotel. Hill appeared in town, held rallies and called Hanley’s non-affiliated AFCGE a “paper local,” its people “a bunch of finks” and added that he was “not particularly impressed with Mr. Bramlet.”

In September, the AFCGE, Seafarers, Culinary and Machinist unions entered NLRB elections at Jerry’s Nugget and Silver Nugget in North Las Vegas and the Desert Inn on the Strip, while holding off at the Dunes. The Seafarers and Mechanics, charging unfair labor acts and firings of employees for union activities, picketed outside the Dunes and Silver Nugget while the AFCGE picketed the Carousel Club.

The election results from the three casinos shocked the unions – 77 Desert Inn gaming workers voted for no union representation, with the Seafarers garnering 42 ballots, the AFCGE and Culinary only one vote each. Jerry’s Nugget voted 38 to 14 against any unionization. All four lost at the Silver Nugget as well, the AFCGE garnering only four votes out of 72 employees. Just 76 casino workers voted for any one of the four unions.

Hanley, whose union succeeded only in tentative representation of dealers at the downtown Golden Gate casino, had now entered his fourth year trying to build his organization. His defeat in the 1967 votes proved devastating for the prospects of the underfunded AFCGE.

Hanley arrested in kidnap, attempted murder

The wheels started to fall off for Hanley in 1968 when he found himself in yet more dire legal straits linked to violent acts. That May, he landed in county jail on attempted murder, attempted robbery and kidnapping charges in the abduction and beating of his one-time bodyguard and union organizer Michael Marathon. Undaunted and out on bail, Hanley lodged allegations of unfair labor practices against the Silver Nugget with the NLRB. Then he was arrested again, for allegedly hiring three men to pound a metal shop owner with a pipe and robbing him of $526. Deputies claimed the victim’s ex-wife hired Hanley to beat the man up.

Hanley’s trial in his alleged 1966 attack on the IRS agent was set for August 29. Meanwhile, deputies sought him on charges of extorting money from the owner of the Nevada Club casino, who claimed Hanley demanded a cash payment to call off a picket line.

The kidnapping and beating brought Marathon to the table as a witness in the two-year-old Alsup shotgun murder case. Sheriff Ralph Lamb hinted that Marathon might provide evidence in the murder, which Las Vegas authorities suspected had ties to contemporaneous shotgun slayings of two labor officials in San Francisco – painter’s union leaders Don Wilson of Local 4, killed on April 5, 1966, and Lloyd Green of Local 1178, shot on May 5, 1966.

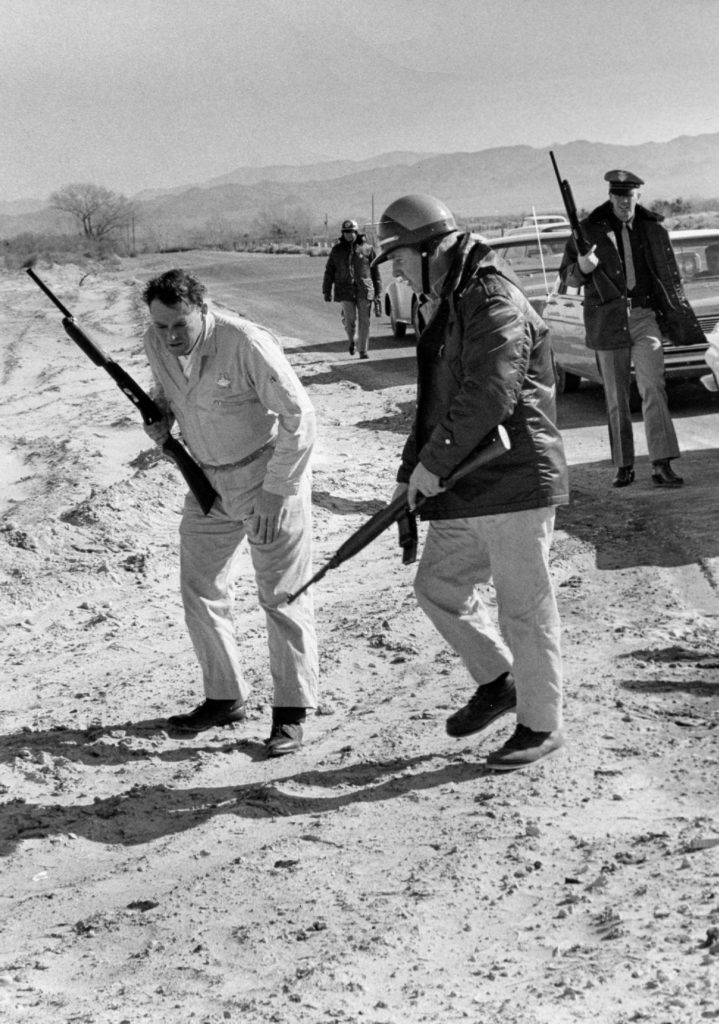

On May 27, 1968, Hanley turned himself in amid warrants for his arrest in Alsup’s murder. A picture of his arrest hit the Review-Journal’s front page. The sheriff’s office further issued warrants in the Alsup murder for two other men, Norman Call (aka Paul Lombardino) and Carl Black (aka Carl Schwartz), also suspected in California in the 1966 killings of Wilson and Green. A judge in San Francisco later exonerated Black in the Wilson murder. The backlog of allegations against Hanley included the Alsup murder, Marathon kidnapping, extortion, criminal libel, assault of an IRS agent and robbery.

A justice of the peace rejected Hanley’s request for bail on the murder charge and bound him over for trial. Deputy District Attorney Earl Gripentrog said that Hanley “is capable of hiring people to kill – to eliminate witnesses.” At trial, Marathon testified that Hanley offered Black $5,000 “to eliminate Alsup,” and that Black replied: “We’ve arranged for a trigger man to take care of Alsup, all we need is the money and the job will be taken care of.” The witness identified the unique 12-gauge pump shotgun located near Alsup’s murder scene as the one owned by Hanley, who Marathon said “kept it under his bed. … I’ve fired it myself.”

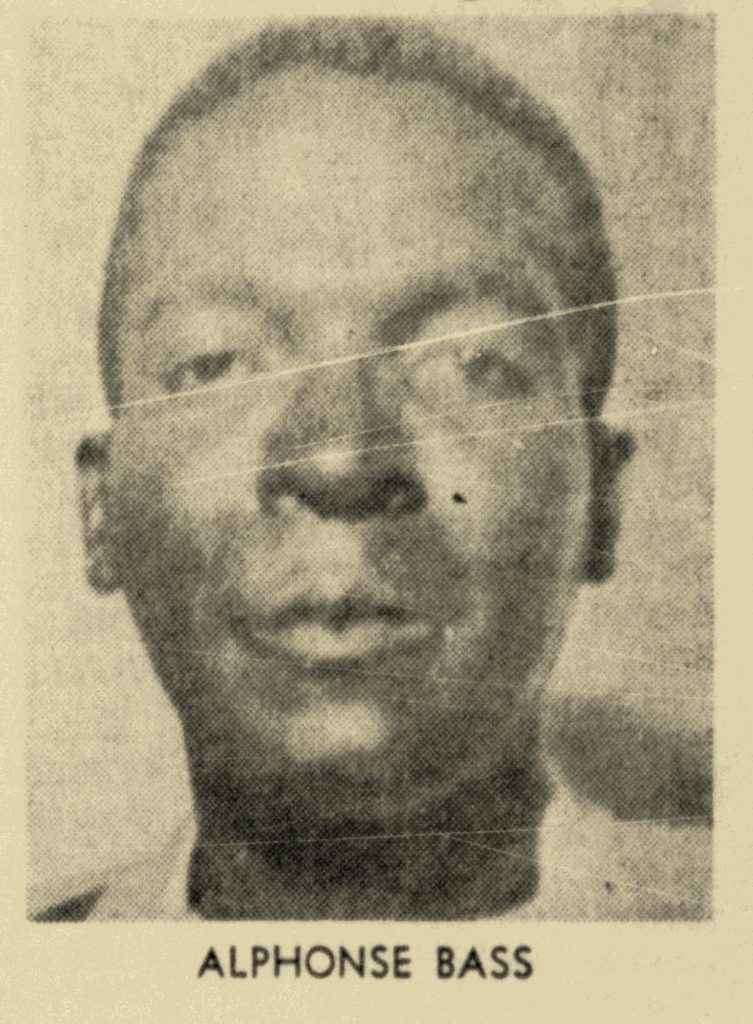

Also during the hearings, the witness Alphonse Bass, a former union employee and handyman for Hanley, said he saw Hanley together with Black and Call and a cab driver named Marvin Shumate in late 1965 before the Alsup homicide. Bass said he witnessed Hanley give $5,000 to Black at the Horseshoe casino. As for Shumate, a potential witness against Hanley, it was too late. He was found beaten and shotgunned to death in the desert by Sunrise Mountain east of Las Vegas in December 1967.

Hanley fired, casino union disbands

With Hanley still behind bars without bail, Dale Hill, president of the AFCGE, based on support from union officers and members, declared in August he had fired Hanley as business manager and suspended him as a member. Only about 100 members remained – Hanley claimed it once had 4,500. Hill said he intended to keep on organizing and seeking contracts. The AFCGE still had only one tentative bargaining unit at the Golden Gate. Days later, the NLRB stated it might abolish the union completely. In September, Hill and a new group of officers took over AFCGE. Meanwhile, a county grand jury indicted Call and Black on murder charges. Sheriff’s investigators heard from an informant who quoted Black saying, “We got rid of that (Alsup) loud-mouthed so-and-so.”

In November, a federal judge sentenced Hanley to one year in prison, after he pleaded to a reduced charge of interfering with the IRS agent. The next month he was admitted to a hospital for a heart ailment.

At Black’s preliminary hearing in the Alsup murder, his ex-wife, Barbara Simmons, claimed Black agreed to furnish Hanley a “triggerman to get rid of Ralph Alsup.” Black, she said, replied, “We will just put a shotgun through his belly and the debt Tom owes Alsup will go to his grave with him.” Marathon also testified Hanley “asked Black if he could arrange to have somebody kill Alsup, and Black said he could for a price. Tom said a shotgun would be used in the slaying.”

But late in December, a judge threw out the testimony from Bass against Hanley and Black as inconsistent and “incompetent.” Herron, Hanley ally and new business agent of AFCGE, disputed Marathon’s testimony, saying that Marathon was in Reno organizing for the union when the supposed Alsup murder conspiracy took place in December 1965. Other defense witnesses placed Hanley at the ranch he owned in Colorado when Alsup died. Prosecutors presented a new witness, casino dealer Truman Scott, who claimed Hanley was in Las Vegas at the time of Alsup’s death. Hanley lawyer Claiborne argued in a writ that his client should be freed because Bass and Marathon had lied.

With the trial in recess, on January 10, 1969, AFCGE president Dale Hill said members had voted to dissolve the union, due to a lack of funds to remain in operation and because the NLRB was looking at disbanding it.

Trial witness dies in arson fire

On March 30, 1969 – a day before Hanley began his federal prison sentence at Terminal Island in Los Angeles – former key trial witness Bass, living for free in a Las Vegas home owned by Hanley’s sister Jane Fitzgerald, was found unconscious in a suspicious fire at the residence in eastern Las Vegas. He died hours later of severe burns and smoke inhalation. An autopsy found the sleep-inducing barbiturate drug Tuinal in his system, but not a lethal dose. Fire investigators determined it was deliberately set with accelerants in several spots outside the home.

Hanley attorney Albert Dreyer denied his client was involved. The sheriff’s office in late April arrested Leroy Allen Marsh, 28, a veteran criminal and former cellmate of Hanley’s in Las Vegas, on suspicion of conspiring to murder Bass and burglarizing a guest room at Caesars Palace. In May, prosecutors also charged Hanley in the murder of Bass, accusing him of hiring people to kill him. The NLRB that month formally dissolved the AFCGE. In the coming years, various efforts came and went, but the drive to unionize casino workers in Las Vegas eventually fizzled.

At the preliminary hearing in the Bass murder, witness and ex-con Joseph Vineze testified that while in county jail with Hanley, he witnessed Hanley telling Marsh he would get him out of jail in exchange for killing Bass, and Marsh agreed. “Bass was to be disposed of,” Vineze said. “I won’t be implicated” in the murder, he said Hanley told him. However, under intense cross-examination by defense attorney Louis Weiner, Vineze could not recall the dates he spoke with Hanley. Judge Joe Pavlikowski then stated, “I’m not sure of any of the conversations myself.” In July, Pavlikowski, based in his opinion on an absence of evidence, threw out the murder charge against Hanley.

Was it lack of evidence? Did sheriff’s detectives conduct a thorough investigation of the Bass murder? Did Hanley’s powerful local friends such as Binion and Claiborne play a factor? Again, in her book, Hanley’s former wife Wendy wrote that Tom Hanley did hire someone to kill Bass – Gramby, whom she claimed drugged and incapacitated Bass and set fire to the house, leading to the death of the Alsup case witness.

Still in the federal pen, Hanley didn’t have much time to celebrate. In August 1969, a federal grand jury in Las Vegas indicted him and Dale Hill on allegations that they violated U.S. labor laws by using their positions with AFCGE to extort Robert Van Santen, Nevada Club casino owner, for money to prevent a picket line. The jury accused Hanley of threatening the casino man into giving him a $2,500 loan in 1968 and Hill of demanding a $50-a-day salary as “casino manager.” They were also charged in state court with criminal libel for union picket signs claiming the Nevada Club employed “bust out” dealers and ran “rigged” slots.

In December, Hanley pleaded not guilty in the murder of Alsup. His trial would commence in April 1970. He also faced a charge of assault with a deadly weapon in the Marathon beating. In January 1970, having completed the last days of his federal sentence in the Clark County jail, U.S. marshals escorted him to federal court in Las Vegas where a judge promptly jailed him on the Nevada Club extortion charges. He and Hill were bailed out several days later.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org