Joseph Valachi’s autobiography reveals Mafia’s inner workings

Historian expands online access to first-person account of Mob history

The Mafia’s early U.S. history has been dramatized in novels and movies but rarely has it been detailed in true first-person accounts. One exception is The Real Thing, an autobiographyby Joseph Valachi, a made member of the Mafia for three decades beginning in 1930.

Valachi hand-wrote the manuscript while in prison before his famous televised testimony in 1963 revealing the Mafia’s inner workings. In 1980, journalist Peter Maas donated Valachi’s manuscript to the National Archives’ John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Maas had interviewed the mobster and used the autobiography as source material to write the best-selling The Valachi Papers, published in 1968. Four years later, the book was made into a movie of the same title starring Charles Bronson as Valachi.

For a long time, Valachi’s original manuscript was available only at the JFK Library in Boston. In recent years, however, Mob historian Thomas Hunt has made it accessible to anyone, free of charge, at the mafiahistory.us website.

The kiss of death

Early in his criminal career, Valachi, born in 1904, was a burglar and getaway driver in New York City with other hoodlums called the Minutemen. The gang’s name referred to the length of time it took for them to pull off a break-in and flee.

Eventually Valachi became a heroin dealer and Mafia hit man suspected of having a role in more than 20 killings. Valachi was a soldier in the Genovese crime family, one of New York’s five Mafia clans.

During his Mafia years, Valachi survived the Castellammarese War, a bloody battle in 1930-31 for Mafia supremacy in New York City, but finally was imprisoned in his late 50s at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary on a 20-year narcotics sentence.

At the same federal facility, Mafia boss Vito Genovese, suspecting Valachi of being an informant, applied a “kiss of death” to the subordinate, singling him out to be killed. Or so Valachi believed. Genovese was in prison because he also had been convicted of narcotics trafficking.

Thinking he spotted the inmate assigned to take him down, Valachi beat the man to death with a metal pipe from a prison construction site. It was the wrong person.

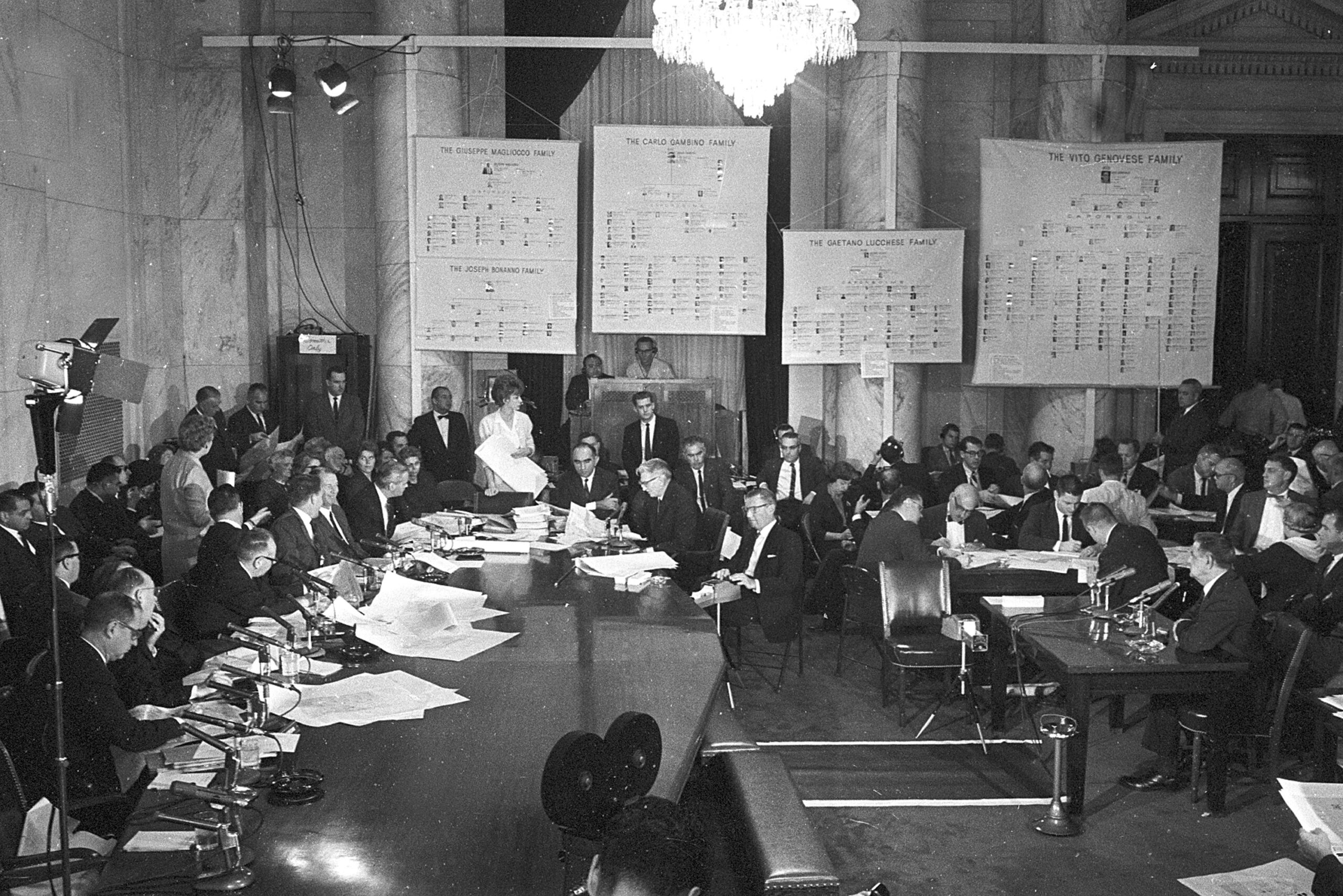

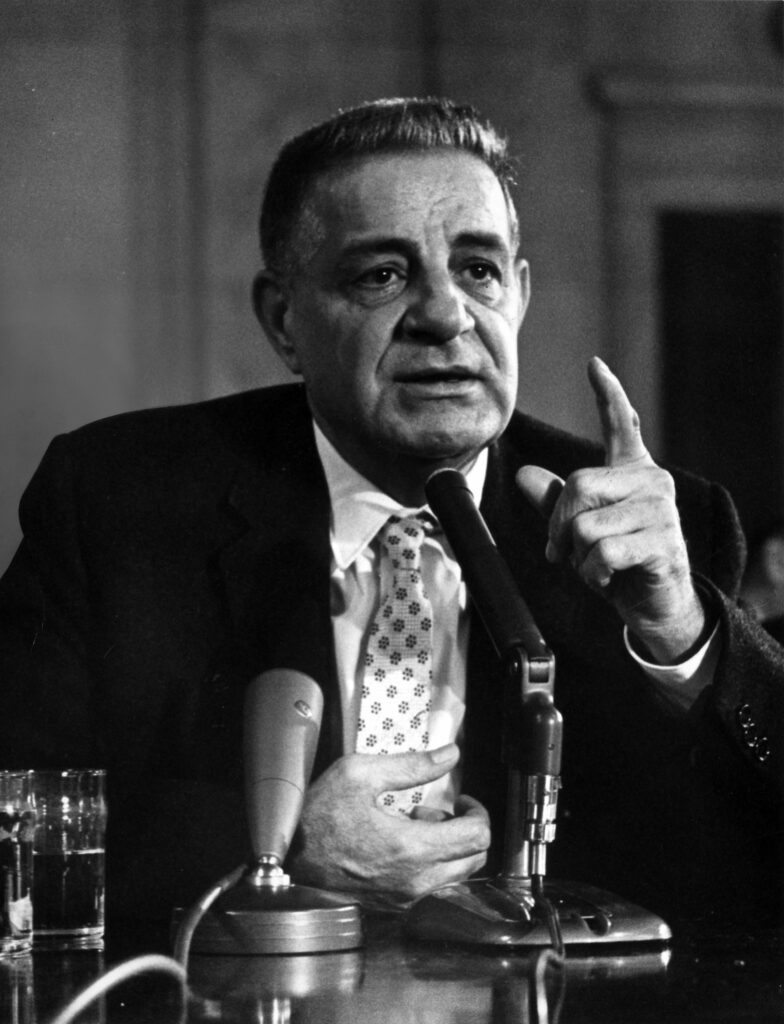

Now with a murder rap adding time to his prison term, Valachi, seeking protection from the Mafia and wanting revenge, agreed to reveal what he knew about organized crime. In 1963, he created a national sensation by testifying before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, led by Arkansas Democrat John McClellan.

During televised testimony, Valachi became the first made member in a public setting to break an honor-bound code of silence known as omertà. Among other secrets, he revealed that the term “Mafia” was not used by insiders. Instead, those in the know used “Cosa Nostra,” meaning “our thing and our family in English,” Valachi said.

In the nonfiction book Five Families, now-retired New York Times reporter Selwyn Raab noted that Valachi “painted the first clear canvas of life inside the Mafia.”

Wearing a suit and tie and occasionally smoking a cigarette, Valachi laid out an explosive narrative that surprised many Americans.

“He confirmed the existence of the five families,” Raab wrote. “He outlined their organizational structure; he exposed the secret ‘blood’ induction ceremony; he explained the effectiveness of the omertà vow; and he identified the leaders of each family, thereby for the first time attaching a name tag to each borgata.”

‘A very different perspective’

Hunt, who administers the mafiahistory.us website, said he posted the autobiography online to make it available for research in an easy-to-read, text-searchable format.

“Those interested in learning the truth about early U.S. Mafia history have very little in the way of primary source material,” he said in an email.

The most accessible account is Mafia boss Joseph Bonanno’s autobiography, A Man of Honor, Hunt said. Another is Nick Gentile’s Vita di Capomafia, but it was published only in Italian and isn’t widely available.

Valachi’s manuscript is the only other major primary source work from the early era, Hunt said.

“Adding enormously to its value, the Valachi autobiography provided a very different perspective than Gentile or Bonanno,” he said.

Unlike other chroniclers of early U.S. Mafia history, Valachi “made no pretense of high social standing or ancient, noble purpose,” Hunt said.

In the manuscript, Valachi describes not only his personal life but the mechanics of rackets such as horse-race fixing, loansharking, slot machines and numbers gambling.

However, most readers probably will be drawn in by Valachi’s account of the Castellammarese War, including the killing of several prominent mobsters during that period, Hunt said.

“As a former aide to top Castellammarese Mafia leader Salvatore Maranzano, Valachi was able to provide an intimate look at that boss and the circumstances that led to his 1931 assassination, without the hero worship found in Bonanno’s book,” he said.

Hunt noted that Valachi had grown up “in a congested New York slum neighborhood.” “He often showed us the reasoning, the misgivings and the principles of a common person, who certainly knew right from wrong and legal from illegal, but grew convinced that living outside the law was the only path available to him,” Hunt said.

The challenges in Valachi’s upbringing come through in the opening sentences of his manuscript. The story begins with his boyhood in “the poorest family on earth.” Valachi said he never got anything for Christmas, not even an apple. Instead, his father would wake him up on that day and offer him a glass of whiskey.

Valachi refused the offer. “It was too strong,” he wrote.

Final years in prison

Years later, after a life of crime, Valachi’s public testimony awakened the nation. Asked what he did for the Mafia, Valachi testified, “I just go out and kill for them.”

Startling remarks like that led to a call for national action. Within several years, federal laws were enacted allowing for court-ordered wiretaps and for informants to be entered into a newly formed federal Witness Protection Program.

Another result was passage of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), permitting authorities to go after syndicate leaders who might not have directly participated in the crimes involved.

Valachi ended up at the La Tuna federal penitentiary just north of El Paso, Texas, where, according to Raab, the mobster obtained, for his cooperation, “the most comfortable treatment and lavish furnishings the Federal Bureau of Prisons could provide.”

Raab, the author of Five Families, explained that this treatment came after authorities learned from surveillance audio that Buffalo Mob boss Stefano Magaddino said Valachi had to die.

As a result, Valachi was housed in a two-room, air-cooled suite at La Tuna. His large cell, isolated from the general prison population and built specifically for him, had couches and a kitchenette.

At La Tuna, Valachi led a “solitary existence, always alone except for guards,” and once attempted suicide by hanging, Raab wrote.

Valachi’s death would come less than a decade after he appeared before the Senate subcommittee. In 1971, while still in federal custody, Valachi died at age 68 of natural causes. He was buried near Lewiston, New York, north of Buffalo, not far from Niagara Falls and the Canadian border.

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. Today, he is a senior reporter for Gambling.com. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org