Ten years ago this month, Whitey Bulger was found guilty on 31 counts, including 11 murders

At trial, Bulger sought unsuccessfully to clear his name as an FBI informant

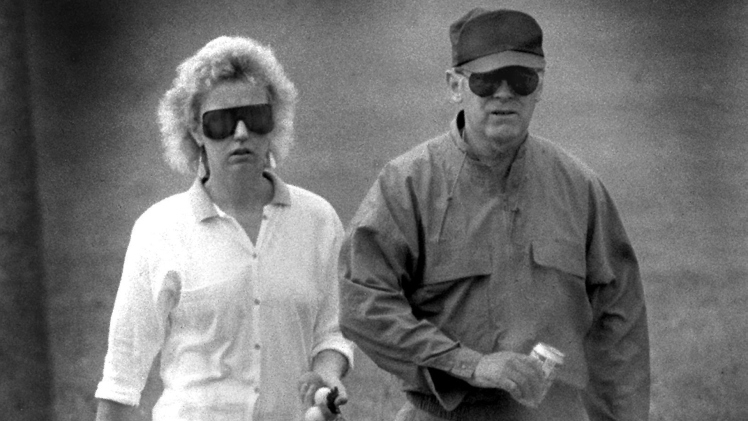

“Have you seen this woman? The FBI is offering $100,000 for tips leading to Catherine Greig’s whereabouts.” Daytime television viewers heard this in a 30-second public service announcement produced by the FBI in 2011. Within days, tips revealed that Greig was hiding out in Santa Monica, California, with her long-time romantic partner and Boston Mob boss James “Whitey” Bulger. The FBI had been searching for the pair since Bulger became a fugitive in 1994. Bulger had risen to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list, alongside Osama Bin Laden. Once apprehended, he was extradited to Massachusetts to face trial.

From 1979 to 1994, Bulger was the leader of the Winter Hill Gang, a mostly Irish Mob, based in South Boston. Bulger and his gang dominated Boston’s rackets with unabashed violence for decades. His biggest advantage was his role as an FBI informant, beginning as early as 1974. Bulger edged out his main Boston rivals, the Patriarca crime family, by providing tips to the Mafia-focused FBI about their activities.

Time after time, Bulger escaped prosecution thanks to the intervention of his FBI handler, John Connolly. Connolly also tipped off Bulger about potential witnesses who “knew too much,” a death sentence carried out by Bulger and his hitmen. Bulger paid Connolly more than $235,000 in exchange for information and a free pass to commit crimes. Connolly was convicted in 2008 of second-degree murder for a leak that led to the death of a potential government witness, John Callahan.

It was Connolly who warned Bulger of his imminent arrest, leading to a 16-year manhunt.

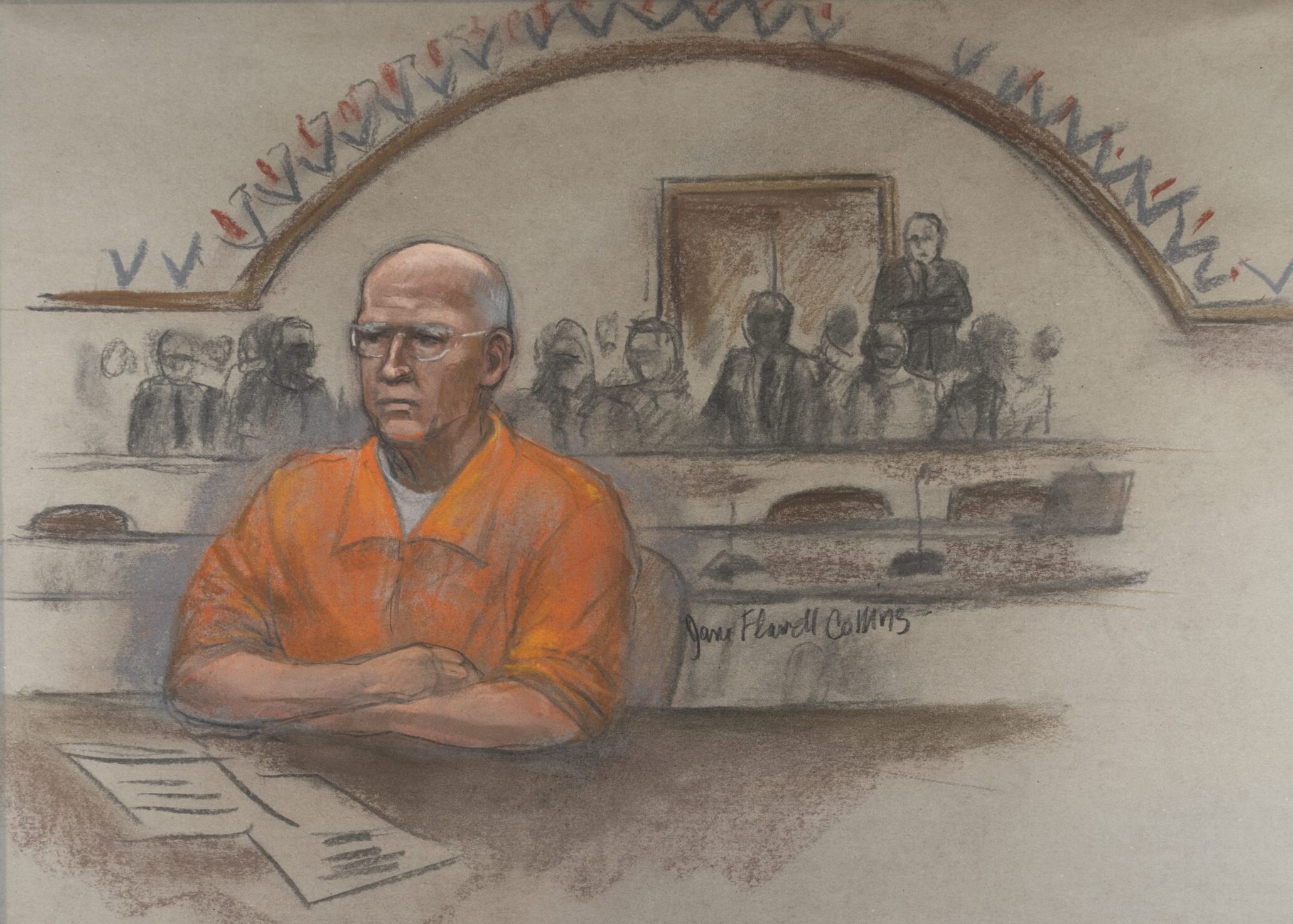

Two weeks after his arrest in Santa Monica, Bulger pleaded not guilty to charges that included 19 murders, extortion and money laundering. He would have to wait another two years for his trial to begin, thanks in part to the successful efforts of his defense team to remove the judge, Richard G. Sterns, from the case because of his relationship with FBI Director Robert Mueller. Presiding in his stead was Judge Denise Casper, the first African American woman appointed as a federal judge in Massachusetts. The trial began on June 12, 2013, with the families of Bulger’s victims filling out the gallery.

Bulger’s defense attorneys did not deny that their client was a prolific racketeer, but they had two main points of contention: Bulger was not an FBI informant, and he was not a killer, particularly regarding the two murdered women, Debra Davis and Deborah Hussey. Being an informant is not a crime and was not among the charges, yet it was a centerpiece of the defense’s argument. The reality was that there was enough evidence to put the mobster away for the rest of his life, so the only thing left to protect was his legacy. Bulger wanted to be seen as Boston’s Robin Hood, a benevolent gangster propped up by government corruption that allowed him to go unchecked for decades.

The defense attempted to claim that the defendant had been granted blanket immunity by deceased federal prosecutor Jeremiah O’Sullivan. In 1978, Bulger was disqualified as an informant because of his involvement in race-fixing at horse tracks. The massive investigation also involved Howie Winter, the Winter Hill Gang boss. FBI agents Connolly and John Morris petitioned O’Sullivan to drop Bulger and his associate Stephen Flemmi from the case because of his information regarding the Mafia. O’Sullivan agreed to drop the two from the case. As a result, Winter was arrested and went to prison, leaving Bulger in charge of the gang.

But Bulger claimed that’s not where the story ends. According to Bulger, O’Sullivan asked the mobster to protect him from assassins in exchange for full immunity over past and future crimes. Judge Casper ruled that the defense would not be permitted to make that argument. In the defendant’s only verbal statement to the court, he said regarding the immunity claim denial, “As far as I’m concerned, I didn’t get a fair trial, and this is a sham, so do what youse want with me.”

Witnesses took the stand one by one as the prosecution chose to focus on the murders. Among the dozens of witnesses were Bulger’s accomplices, including hitman John Martorano, enforcer Kevin Weeks and close associate Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi. Martorano testified about the 20 murders that he committed on behalf of his boss. On the stand, Flemmi claimed that he personally watched his partner strangle to death Debra Davis and Deborah Hussey. Afterward, Flemmi pulled out their teeth to interfere with identification. Weeks told the court that he was with Bulger when he murdered Michael Donahue, an innocent truck driver who was caught in the crossfire when giving a ride to Brian Halloran, a drug dealer turned government informant and Bulger’s intended target. As a counter to their testimony, the defense argued that the witnesses were the true killers, merely pinning their crimes on their boss.

This dramatic trial wasn’t without a surprise twist. Five days in, Stephen Rakes was found dead before he could take the stand and testify against Bulger. In 1984, Bulger threatened to kill him if he didn’t sell his liquor store for $33,000 less than what Rakes and his wife spent to open it. Despite suspicions, the untimely death was unrelated to the trial; an indebted business associate slipped cyanide into his iced coffee.

Defense attorneys began calling their own witnesses on July 26. They called former FBI agents to testify regarding Bulger’s status as an informant and corruption within the Bureau’s Boston office. One of the agents, Robert Fitzpatrick, was Boston’s assistant special agent-in-charge from 1981 to 1986. According to him, John Connolly and his supervisor, John Morris, went to great lengths to make Bulger believe that he wasn’t an informant. Morris refused to honor Fitzpatrick’s request to revoke Bulger’s informant status when he brought up the improper relationship between informer and handler. There was even more reason to dismiss Bulger when Brian Halloran became a government witness against Bulger for the murder of World Jai Alai owner Roger Wheeler. The request fell on deaf ears, as did the recommendation to put Halloran in witness protection. Halloran was murdered after Bulger’s FBI handlers leaked his informant status.

When it was the prosecution’s turn to question Fitzpatrick, they aggressively moved to discount the witness by claiming, “You’re a man who likes to make up stories, aren’t you?” Journalist T.J. English observed that the prosecution grilled the former FBI agent with more aggression and accusation than they did Bulger’s partners-in-murder. The assault continued when Fitzpatrick returned to the courtroom in handcuffs, charged with 12 counts of perjury and obstruction of justice from his testimony at the Bulger trial. He pleaded guilty on all counts and landed two years of probation.

After closing arguments concluded on August 5, the jury deliberated for five days. When they emerged, Bulger was found guilty on 31 counts, including 11 of the 19 murder charges. In November 2012, Judge Casper sentenced Bulger to two consecutive life sentences plus five years in prison. As expected, Bulger would spend the rest of his life in prison. In a separate trial, his accomplice and girlfriend Catherine Greig received eight years in prison and a $150,000 fine for her involvement in aiding a fugitive. (Greig was released from prison in 2020.)

When Bulger arrived at the Coleman II federal penitentiary in Florida, warden Charles Lockett knew that the one-time informant Mob boss had to be separated from the general population for his safety. The warden also met with prominent inmates to ensure they wouldn’t hurt the new resident. However, after Bulger allegedly threatened a nurse by telling her, “Your day of reckoning is coming,” plans were made to transfer the now 91-one-year-old mobster.

In 2018, Bulger was transferred to the Hazelton federal penitentiary in West Virginia. Less than 12 hours after his arrival, a group of inmates allegedly led by Mob hitman Fotios “Freddy” Geas entered Bulger’s cell and beat him to death with a padlock attached to a belt. Geas was already serving a life sentence for killing former Genovese crime family acting boss Adolfo Bruno in 2003. When asked about his client’s involvement, Geas’ attorney Daniel D. Kelly said that he “has a particular distaste for cooperators.” For all of Bulger’s effort at persuading the world that he was not a government informant, his fellow inmates were not convinced, and for that they took his life.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org