DEA marks 50th anniversary of fighting drug traffickers at home and abroad

Over the years, the DEA fended off several efforts to dissolve the agency or merge it with the FBI

Fifty years ago, a federal agency was created to combat America’s growing drug problem. Officially born in July 1973, the Drug Enforcement Administration has since become the most recognized narcotics enforcement agency in the world.

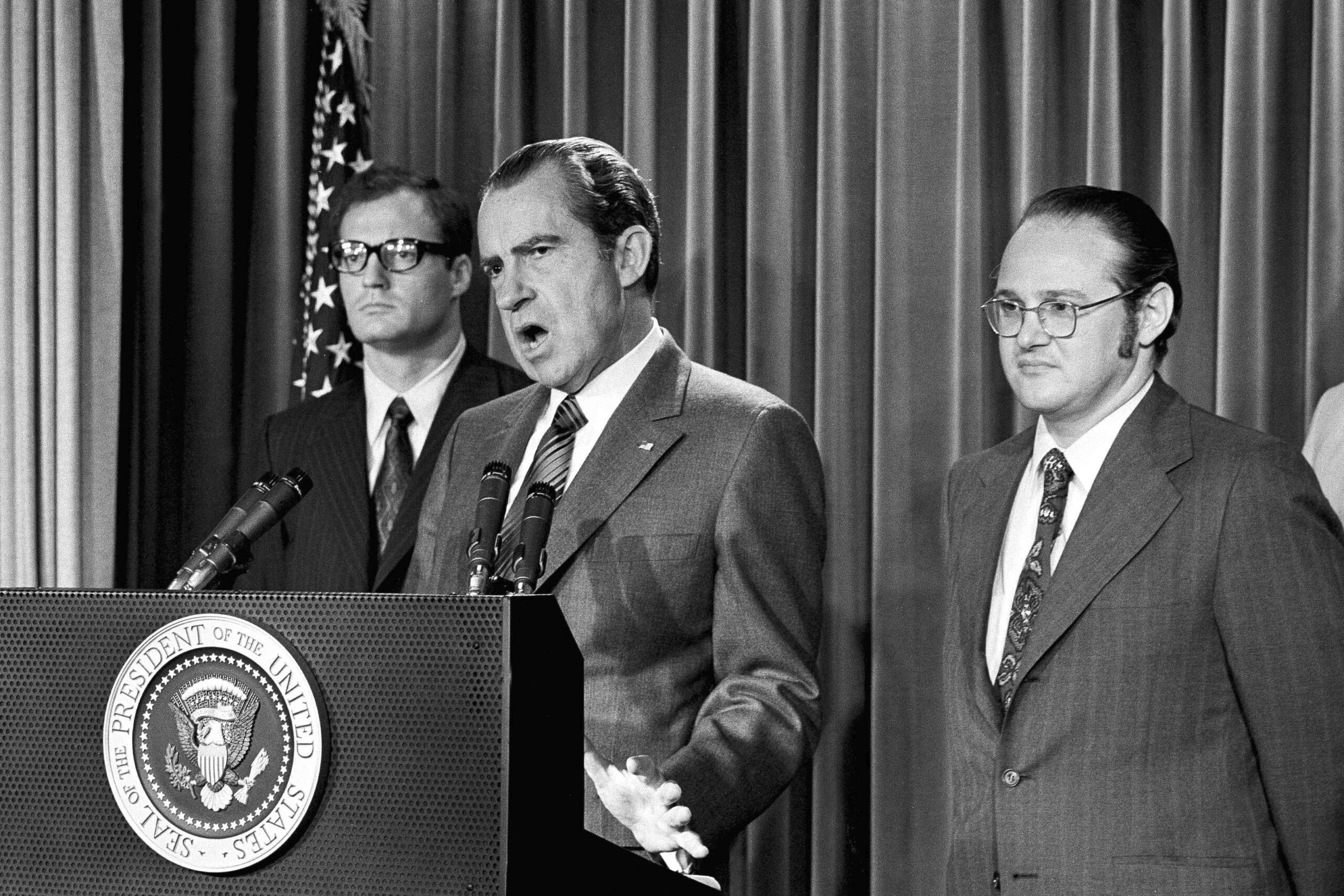

President Richard Nixon famously declared a war on drug abuse in a fiery 1971 speech, but his call to action took another two years to culminate in what became the DEA. The plan was to merge several federal law enforcement agencies, which, according to critics, were collectively on the losing end of the so-called drug war, largely because the separate agencies had little or no interagency cooperation.

“Right now, the federal government is fighting the war on drug abuse under a distinct handicap,” Nixon said in March 1973. “For its efforts are those of a loosely confederated alliance facing a resourceful, elusive, worldwide enemy.” Nixon said the dysfunction enabled “cold-blooded underworld networks that funnel narcotics from suppliers all over the world into the veins of American drug victims.”

The solution to this disjointed system involved a series of maneuvers, including disbanding some of the agencies that once handled the lion’s share of narcotics crime-fighting, enabling budgets and resources to be shifted to the newly created entity. The move harkened back to the formation of the first centralized narcotics agency in 1930, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, or FBN, under the leadership of Harry J. Anslinger. The FBN’s origins were similarly a direct result of a growing problem of illicit drugs paired with independent law enforcement agencies that were often not on the same page. Differing from the DEA, which falls under the Justice Department, the FBN answered to the Treasury Department and did so until 1968 when it merged with the Bureau of Drug Abuse Control (within the Department of Health) to form the Justice Department’s Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs.

Nixon’s Executive Order 11727 described creation of the DEA:

“Reorganization Plan No. 2 of 1973, which becomes effective on July 1, 1973, among other things establishes a Drug Enforcement Administration in the Department of Justice. In my message to the Congress transmitting that plan, I stated that all functions of the Office for Drug Abuse Law Enforcement (established pursuant to Executive Order No. 11641 of January 28, 1972) and the Office of National Narcotics Intelligence (established pursuant to Executive Order No. 11676 of July 27, 1972) would, together with other related functions, be merged in the new Drug Enforcement Administration.”

Today, the DEA’s official mission statement and purpose “is to enforce the controlled substances laws and regulations of the United States and bring to the criminal and civil justice system of the United States, or any other competent jurisdiction, those organizations and principal members of organizations, involved in the growing, manufacture, or distribution of controlled substances appearing in or destined for illicit traffic in the United States; and to recommend and support non-enforcement programs aimed at reducing the availability of illicit controlled substances on the domestic and international markets.”

The DEA has a long and storied past. It’s not unusual for new ideas and institutions to shake things up, particularly when it comes to government and policy changes. The DEA’s fledgling years were not immune to the resistance of change. The agency’s infancy faced obstacles. Only a few years after its inception, the DEA had detractors, both from the public and from politicians. Changes within its early leadership added to the growing pains and challenged the DEA’s resolve.

The agency did have proponents and self-determination, though, as demonstrated at one point in 1977 when it was at the center of a controversial idea raised by then-Attorney General Griffen B. Bell. The short-lived and hotly contested plan involved studying the possibility of having the DEA absorbed into the FBI. That wouldn’t be the last time ardent challengers of the agency’s effect and success rate would surface in headlines. It’s the federal government, so naturally squabbles were common and interagency rivalries smoldered. In 1980, less than a year into President Ronald Reagan’s presidency, a delegation of disgruntled Customs officials demanded Congress either reorganize the DEA or abolish it altogether. Despite all the obstacles, the DEA forged ahead into the 1980s, a time that would provide both shining successes and one of the darkest periods in its history.

Any of the past rivalries, internal disruption and political saber rattling was a mere inconvenience when compared with the harsh reality DEA agents faced on a daily basis while simply doing their jobs. The darkest day for the DEA was the brutal torture and murder of agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena in Mexico in 1985. Those held responsible included leadership of Mexico’s then-dominant drug trafficking organization known as The Federation, or Guadalajara Cartel. Bringing those responsible to justice was a painstaking effort, marred by potential derailment at nearly every turn thanks to systemic corruption within Mexico’s legal and political machines. The mission took time, but eventually the top kingpins were apprehended, and some of them were extradited to stand trial in the United States.

The 1980s and early ’90s also saw the rise of the “cocaine cowboy” era and put names such as Colombia’s Pablo Escobar into the limelight and the sights of the DEA. In December 1993, working closely with Colombian police agencies, the DEA helped to locate and take down the world’s most infamous and dangerous kingpin of the time. DEA agents Steve Murphy and Javier Pena led the agency’s efforts in taking down Escobar, a story that inspired the popular Netflix series Narcos.

In the 21st century, the DEA has played a critical role in narcotics issues such as fighting the Mexican drug cartels and the fentanyl crisis. The final capture and extradition of Mexico’s most infamous drug trafficker, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, in January 2016 proved to be a profound accomplishment for the DEA and all the cooperating agencies involved. Guzman’s record of escapes and elusion was epic, but his freedom finally ended in 2016, captured in Mexico six months after staging an unprecedented engineering marvel of a prison escape. The Sinaloa Cartel leader was convicted during a three-month trial in New York in 2019 and sentenced to life in prison. He is expected to serve the rest of his life in the supermax prison in Colorado.

After the sentencing, DEA Acting Administrator Uttam Dhillon said:

“This sentencing shows the world that no matter how protected or powerful you are, DEA will ensure that you face justice. This result would not have been possible without the dedication and determination of so many brave men and women of the DEA, who worked tirelessly to see the world’s most dangerous, prolific drug trafficker behind bars in the United States. This is a huge victory for the rule of law, for thousands of current and retired DEA agents and analysts worldwide, and for all of our law enforcement partners here, in Mexico, and across the globe.”

Today, the DEA has about 10,000 employees with 241 domestic offices and 93 foreign offices in 69 countries.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org