How Prohibition changed beer

Did the big beer brands really get bigger and blander, or is there more to the story?

For dedicated home brewers and beer snobs, the tale is familiar. Prohibition killed small and mid-sized breweries, and after repeal, the few breweries left — behemoths such as Anheuser-Busch and Pabst — had to do everything in their power to cut costs. This story is true, but it does not give us the whole picture. Prohibition had profound effects on beer, and some of the off-stated stories about these effects have formed a mythology that doesn’t hold up when you examine the historical record more closely.

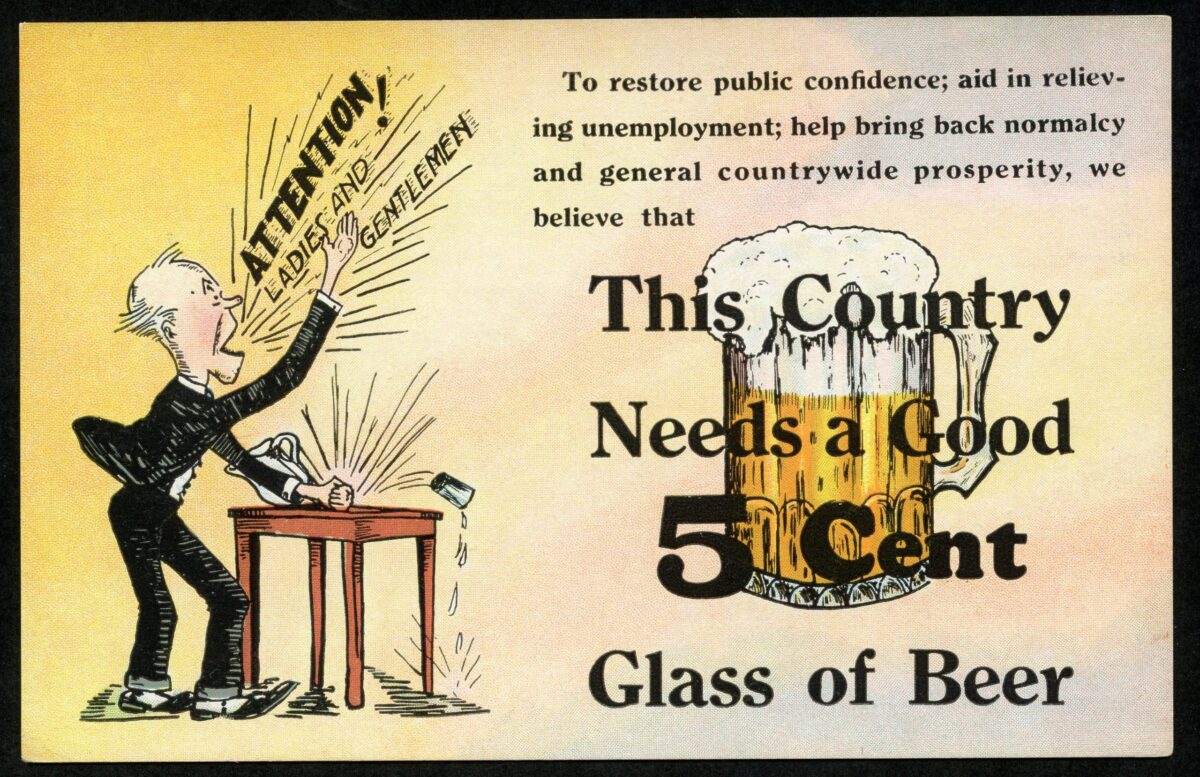

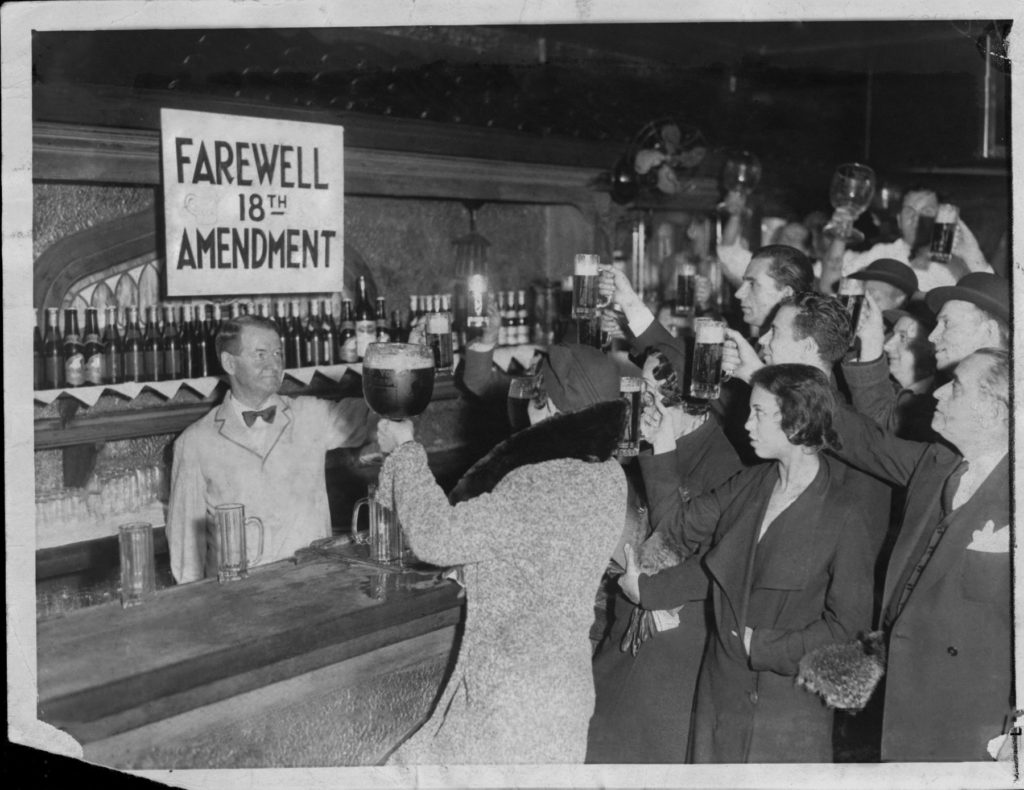

In honor of New Beer’s Eve, which commemorates the day in 1933 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Cullen-Harrison Act, re-legalizing beer for the first time since Prohibition took effect in 1920, let’s explore the ways Prohibition changed the American brewery landscape.

American lager and palatable brews

Before the craft beer revolution of the past few decades, the United States was most commonly associated with the bright, yellow lagers of breweries such as Budweiser, Pabst and Coors. Lagers have been the king of the brewing scene since the 1840s. Before large waves of German immigrants began settling in the United States in the 1840s and ’50s, Americans drank ale. The first wave of English settlers brought ale to the new world, a style that fermented at warmer temperatures than lagers and had a knack for filling bellies and warming bodies. Ales brew more quickly than lagers, but they don’t stand up as well to long-term storage or transport, which ultimately led to their demise in the vast American continent.

As soon as English settlers landed in North America, ale suffered from a serious of setbacks. At first it was the lack of barley, which farmers remedied. Then it was competition from rum and whiskey, which was not as easily fought. These setbacks led to experimentation with fermenting different ingredients, including corn, pumpkin and spruce. Numerous Native American cultures had some form of fermented corn beverage. Ultimately, experimentation didn’t change much, and beer became less popular than hard spirits in the American colonies.

This began to change in the middle of the 19th century when German-Americans established breweries across the Northeast and Midwest. Americans of all ethnicities and nationalities fell hard for this clean, smooth-drinking beer. Lagers tasted fresher, traveled more easily and looked more effervescent in a glass than the old English ales.

One ingredient that led to the bright, bubbly new beers of the mid-1800s was rice. Brewers experimented with the process of adjunct brewing, making beer with grains other than barley. They first tried corn, but the results were oily. Then they tried rice, an addition that was originally heralded as an improvement. And a surprise to many today — adjunct-brewed beers were actually more expensive to make than conventional all-malt versions. Rice was not perceived as an inferior ingredient until recently.

The Midwestern brewers in particular had an interesting challenge, as explored in Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer by Maureen Ogle. They were incredibly successful in their own towns, but even Milwaukee, Chicago and St. Louis were relatively small in the 1850s and ’60s. In order to grow their operations, they expanded across the Midwest and as far away as Texas and California. They cornered the market on distribution and transport while brewers in New York, Philadelphia and other East Coast cities were content to serve their local populations.

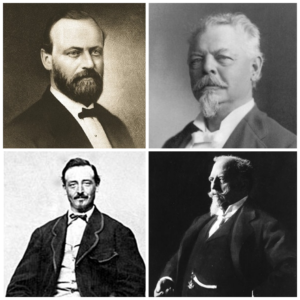

The success of German-American brewers such as Joseph Schlitz, Frederick Miller, Adolphus Busch and Frederick Pabst had a number of consequences. Their lagers became the perceived standard of quality and taste. They continually reinvested in more technologically advanced machinery and were able to negotiate lucrative deals for raw materials and distribution.

In the end, the success of German-American brewers contributed to breweries’ downfall and Prohibition. As the temperance movement became more politicized around the time of World War I, anti-German sentiment reached a new high, and a lot of Prohibition propaganda focused on demonizing German-American brewers.

The end of the ‘tied system’

If modern connoisseurs walked into a late 19th century saloon, they would be sorely disappointed by the beer selection. Almost every restaurant, hotel and saloon in the United States was part of the “tied system.” Tied houses, which are saloons owned and controlled directly by a brewery, originated in England. They arrived in the United States because of pressure from temperance advocates who saw saloon owners as unscrupulous thugs eager to turn a profit however they saw fit. Before the tied system, many saloons operated brothels or illegal casinos as well. As local law enforcement and revised ordinances cracked down on these dens of ill repute, brewers such as Schlitz and Anheuser-Busch purchased existing saloons and turned them into brand-specific beer halls.

At first temperance advocates were mildly placated because brewery-owned saloons were more likely to follow the letter of the law. But the tied system led to an increased proliferation of saloons. If Schlitz opened a public house on one corner, then Blatz, Pabst and Miller were likely to open competing operations on the other three corners. Besides increasing the accessibility of alcohol in many communities, prohibitionists complained that these tied-system saloons were operating as secret social and political societies that furthered the liquor cause and pro-immigrant sentiment.

When Prohibition was repealed, tied houses were effectually outlawed. A three-tier system was established to define and separate producers, distributors and retailers. Although many states have since loosened restrictions on brewery-owned retailers — think microbrewery brewpubs — the tied system ended along with Prohibition.

Decorative, informative tap handles

Another change was the proliferation of clearly labeled tap handles. Before Prohibition, most kegs or draft faucets were fashioned with nondescript black ball-shaped knobs. A distributor or bartender might scrawl a brand name or insignia on the knob, but breweries rarely, if ever created branded tap handles. In the 19th century, no regulations mandated clearly labeled beer taps.

Once Prohibition ended, many states realized they needed to enact new local protocols to protect consumers. In Pennsylvania, a 1935 bulletin established the following regulation, which is still enforced by the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board: “. . . shall be unlawful for any retail dispenser to furnish or serve any malt or brewed beverages from any faucet, spigot or other dispensing apparatus unless the trade name of brand of the product served shall appear in full sight of the customer and in legible lettering upon such faucet, spigot or dispensing apparatus.”

In addition to new regulations, many breweries saw themselves faced with new marketplace competition for the first time. Pre-Prohibition saloons rarely served more than one brewery’s beer. Even at a higher-end hotel or restaurant, the average imbiber did not expect a cornucopia of choices. But after repeal, breweries needed to find ways to visually stand out.

Since Prohibition’s repeal, tap handles have become increasingly ornate and decorative. The first branded tap handles were simple, modified versions of the ball knobs. They would have the brand name and possibly a recognizable logo on the front face. By the 1950s, breweries were experimenting with different shapes, sizes and materials to set their taps apart, and this creative one-upmanship continues to this day.

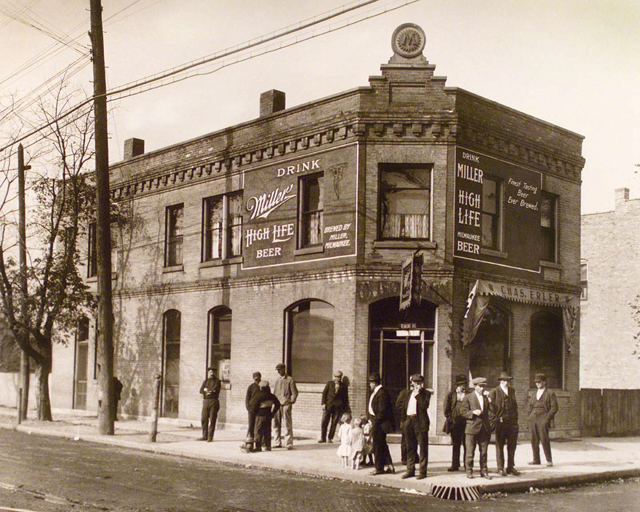

New markets, new ads

Another area where breweries shifted their focus after Prohibition was how they advertised and who they advertised to. Breweries had become astute marketing agencies in their own right during the 19th century, but it was not until after repeal that they focused on marketing beer as a leisure activity that could be done at home. New advertisements showed men cracking open a can — a new invention introduced in 1935 — after a long day of work. Some even showed families at picnics. By the late 1940s, Miller was directly promoting Miller High Life as the “Champagne of Bottle Beer,” with full-page color ads in women’s magazines such as Vogue and McCall’s.

Loss of diversity

Prohibition killed thousands of small breweries around the country. The breweries that were able to weather 13 dry years were those that already had diverse enough portfolios and deep enough coffers to make alternative products for diminished profits during Prohibition. According to Maureen Ogle, of the 1,300 brewers operating in 1915, no more than 100 survived Prohibition.

It is worth noting, though, that in the 1870s there were 4,000 breweries. Between the 1880s and 1910s many small and mid-sized breweries folded because of temperance pressure or consolidation with other breweries for financial reasons. Prohibition had an immediate effect on those breweries still operating in 1920, but it is not cut and dry. Corporate consolidation happened in nearly every American industry between the late 1870s and 1900. This Gilded Age phenomenon affected vertical integration, as seen in the tied system and the transportation operations that many breweries handled themselves. It also led to large monopolies and corporations. It is likely that even without the hastened death of breweries thanks to Prohibition, the United States would have continued losing smaller breweries to consolidation throughout the early 20th century.

In the intervening decades, beer has recovered and grown exponentially. Today there are more than 7,000 breweries in the United States, an all-time high. The nation’s brewing capacity was 80 million barrels in the year after Prohibition, and consumption was less than half of that. Decreased interest in beer was due in part to the mobsters, bootleggers and moonshiners who peddled poorly brewed beer during Prohibition. Thankfully for trained brewers, it was not long before Americans remembered why they loved the stuff.

According to figures compiled by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau as well as the Brewers Association, today the United States is producing about 200 million barrels for national consumption and five billion barrels for export annually.

On April 6, raise a glass to the return of beer, and keep in mind the lasting consequences of Prohibition on our favorite fermented beverage.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org