Ten alternative products made by breweries during Prohibition

Companies found innovative ways to stay afloat after main products were outlawed

American businesses have become adept at producing alternative products during the global Covid-19 pandemic. Distilleries have been producing hand sanitizer and industrial disinfectants. Breweries, vineyards and brewpubs have found ways to repackage and sell their wares through drive-up queues and online marketplaces. But 2020 was not the first time the liquor industry needed to pivot.

Many businesses faced a similar challenge on January 17, 1920, when Prohibition went into effect, and the manufacture, sale and transport of alcohol was banned across the United States. For 13 years, a number of industries were forced to change direction in order to remain in business. Restaurants explored ways to entice patrons without wine and beer. Truck drivers who previously delivered kegs found new routes. Wineries, distilleries and breweries were arguably in the toughest position of all. Although many simply shuttered, some brainstormed new ventures that sustained them during Prohibition.

In honor of the 101st anniversary of Prohibition, here is a look back at 10 alternative products made by breweries during Prohibition.

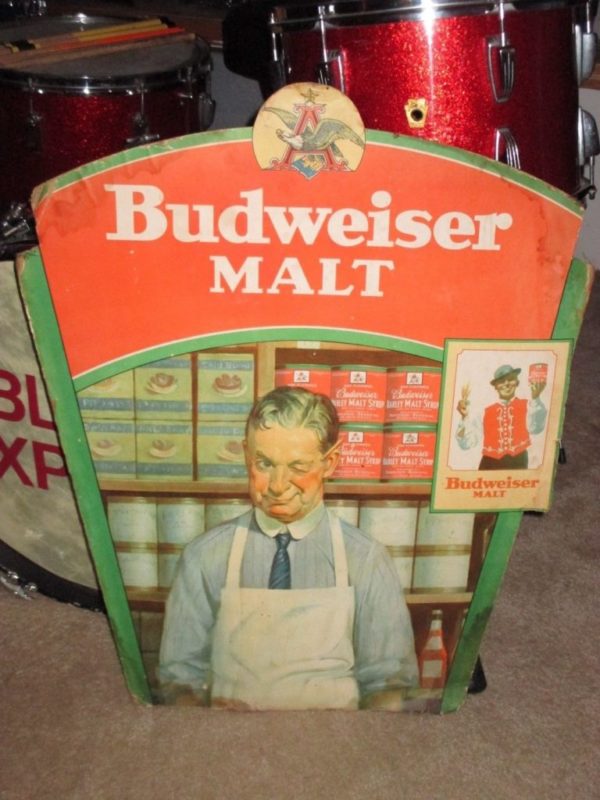

10. Barley malt syrup

Malt syrup ranked high on the list of obvious products for struggling breweries. Although the 18th Amendment went into effect a full year after it was ratified, most breweries knew their best chance at success was to pivot quickly to a product that used similar ingredients, machinery and industrial processes. Malt syrup fit the bill. Many breweries produced malt syrup, including Anheuser-Busch, Schlitz and Miller.

So what exactly is barley malt syrup? It is a thick, unrefined sweetener produced from malted barley, which happens to be one of the primary ingredients in beer making. Malt syrup is used to make malted milk, and it had a market before Prohibition from confectioners, bakeries and soda shops. But during the dry decade, malt syrup took on a subversive quality. A lot of it was not destined for malted milkshakes or candy bars. It was sold with a wink to consumers who intended to use it for home brewing.

9. Brewer’s yeast

Malt syrup alone does not make beer. To corner the market on home brewing, breweries also sold brewer’s yeast. Anheuser-Busch packaged its yeast, which it has famously kept alive since the 1880s, in five-pound cakes. Wrapped in wax paper and available in groceries, the brewer’s yeast was specifically formulated to allow home brewers to make great-tasting beer.

Brewer’s yeast is different from the active dry baker’s yeast used to make cakes and bread. Although both are made from strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungus, brewer’s yeast contains chromium. Both yeasts create carbon dioxide, but brewer’s yeast also assists in increasing alcohol content as it feeds off the sugar present in malted barley.

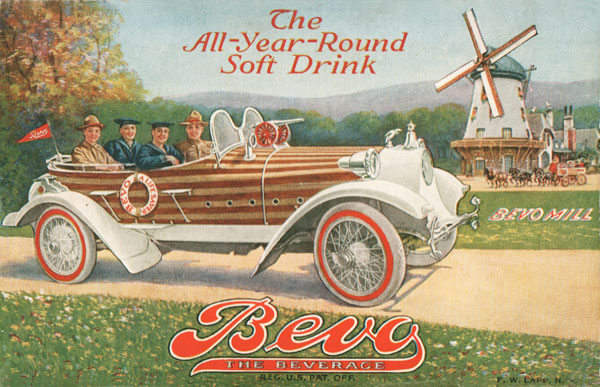

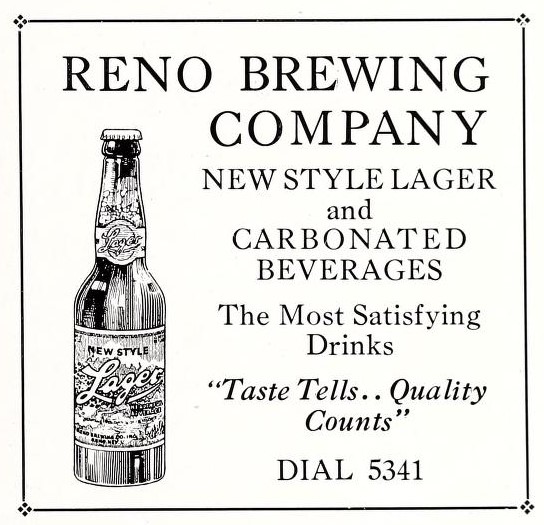

8. Near beer and soft drinks

“Near beer” was another no brainer for breweries during Prohibition. For those unfamiliar with the term, near beer refers to what is legally called non-alcoholic beer, a fermented beverage containing less than 0.5 percent alcohol by volume. Under the Volstead Act, the companion law that defined intoxicating beverages and established enforcement parameters for Prohibition, near beer was legal.

Many breweries already produced near beer before the passage of the 18th Amendment. Statewide prohibitions existed in three dozen states before the official start of Prohibition in January 1920. Near beer was promoted as a hearty, healthy drink. Advertisements aimed at pregnant and nursing mothers touted the benefits of malt in a baby’s diet as well as in supporting a mother’s milk supply.

Near beer production increased during Prohibition, and most breweries that remained open produced their own version. Budweiser made Bevo. Pabst Blue Ribbon made Pablo. Schlitz made Famo. The Reno Brewing Company in Nevada made New Style Lager, an optimistically named near beer advertised as “the most satisfying drink.” Ultimately, consumers were not satisfied, and although near beers persist today for niche audiences, most Americans were not impressed by Bevo, Pablo or Reno’s New Style Lager.

Breweries also made soft drinks such as ginger ale, sarsaparilla and fruit-flavored sodas. Some breweries were able to develop local followings for their specific soft drinks, but most abandoned these products after Prohibition.

7. Candy

Candy was a popular idea for breweries, and quite a few produced some sort of sweet treat or confectioner’s ingredient. Milwaukee’s Blatz made grape- and mint-flavored chewing gums. Schell’s Brewery in New Ulm, Minnesota, began wholesaling candy made by other companies. Coors became the main supplier for malted milk at the Mars Candy Company and continued to produce malted milk until 1957.

One failed product worth mentioning was Schlitz’s Eline chocolate bars. Although the chocolate itself seemed to be well made, it was packaged on a machine that used fish oil as a lubricant, which in turn gave the chocolate a fishy taste.

6. Ceramics

In 1913, Adolph Coors, founder of the Golden Brewery now known as Coors, became president of Herold China and Pottery Company in Golden, Colorado. When Herold’s founder left the community in 1915, Coors fully absorbed operations and renamed the company Coors Porcelain.

Statewide prohibition in Colorado began in 1916. Between the decreased demand for beer and the increased need for domestic porcelain labware during World War I, Coors Porcelain was poised to become a large part of the Coors empire. During Prohibition it created labware, dinnerware and hotelware as well as promotional products such as ashtrays. It became the global leader in the production of porcelain labware in the 1920s.

Today the company lives on as CoorsTek, and it continues to produce technical ceramics for a range of industries.

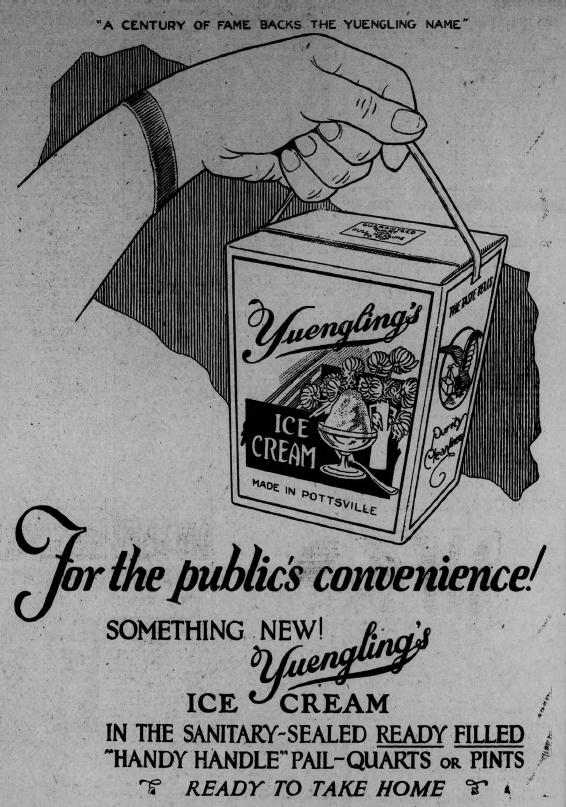

5. Ice cream

Dairy products were another popular category of alternative products because breweries already had equipment for refrigeration, freezing and pasteurization. Detroit’s Stroh Brewery Company, Anheuser-Busch and Pennsylvania favorite Yuengling were among the many breweries that began churning out frozen dairy treats.

Yuengling in particular was successful in the production of ice cream, which began in 1920. By 1931, the ice cream plant had expanded a few times. First, Yuengling purchased additional property in Pottsville, the city of its founding, to enlarge its footprint. Then it established additional branches in Allentown and York, Pennsylvania. These expansions also allowed the company to begin processing and distributing milk. The end of Prohibition in 1933 did not affect Yuengling’s commitment to ice cream, and the company continued operations until 1985.

4. Truck bodies

With new products came even greater need for innovation. Anheuser-Busch was notable for producing more than 25 alternative products during Prohibition. Some of those new products — particularly its ice cream — demanded new transportation methods. Anheuser-Busch developed a vehicle department and began making refrigerated truck bodies and ice cream cabinets. Its technology, called Automatic Brine Circulation, became popular with dairymen, butchers and green grocers, but it was later supplanted by dry ice and electric refrigeration.

In additional to commercial vehicles, the company also produced a recreational vehicle called the Lampsteed Kampkar, as well as a series of promotional vehicles, including the Bevo Victory Boat, an automobile named after its non-alcoholic beer.

3. Artificial ice

Ice cream was not the only frozen product that helped breweries keep the lights on. Rhode Island’s Narragansett Brewing Company was the largest brewery in New England on the eve of Prohibition. Its success rested partially on the pleasant-tasting water derived from the Scituate Reservoir. And it used this water to make more than just beer. Beginning in the 1910s, Narragansett’s holdings included an artificial ice plant and cold storage. It delivered 25 tons of ice to more than 1,500 customers. Artificial ice was still a relatively new phenomenon in the 1910s and ’20s, when most Americans still relied on naturally harvested ice or simply went without.

Once Prohibition began, Narragansett began making medicinal tonics and soft drinks, but its ice production provided a steady capital and customer base to endure Prohibition.

2. Frozen eggs

Possibly the most surprising alternative product of the Prohibition era is Bud Frozen Eggs. Anheuser-Busch began producing 30-pound canisters of frozen egg products in “golden select” and “special whites” varieties. The processes for breaking, separating and freezing eggs was only 30 years old when Anheuser-Busch added this product to its arsenal.

As with many of the alternative products produced during Prohibition, such as malt syrup and Coors ceramics, frozen eggs were marketed for commercial consumers. Frozen eggs are used to this day in the baking industry and within large-scale restaurant operations. Anheuser-Busch’s version showed up in advertisements and company product lines until the 1950s.

1. Processed cheese

Although a handful of breweries experimented with ice cream and Budweiser made a mark with frozen eggs, one of the most innovative dairy products was Pabst-ett cheese. Pabst Brewing Company, of Pabst Blue Ribbon fame, purchased a local dairy at the beginning of Prohibition and began developing a processed cheese that could be marketed as easily digestible, healthful and delicious. What it created was a whey-based product available in cheddar, Swiss and pimento and sold as both blocks and spreads. Pabst Brewing sold more than eight million pounds of Pabst-ett during Prohibition.

At the time, processed cheese was touted as a healthy alternative to natural cheeses. Velveeta created the market standard in 1918. Kraft Foods later acquired Velveeta, and Kraft felt so threatened by the Velveeta-esque Pabst-ett product that it sued Pabst for infringement in 1924 and won. Instead of forcing Pabst to completely fold its cheese operations, Kraft allowed Pabst to continue making the product, and the brewery paid a 25-cent royalty per 100 pounds of cheese produced. After Prohibition ended, Pabst sold its cheese operations to Kraft and returned to making PBR. Although Pabst-ett was short-lived, it has lived on as one of the most iconic examples of Prohibition ingenuity.

Although most of these alternative products are long forgotten, they are a great reminder of the innovation and creativity that can be tapped into in even the most unprecedented of times. And it would be shortsighted to believe that any of these products are merely a part of the past. Yuengling satisfied its loyal fan base’s nostalgia when it reintroduced ice cream in 2014 after a nearly 29-year hiatus. With interest in home brewing increasing in the United States since the start of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020, as well as increased awareness and interest in sobriety over the last few years, who can say whether malt syrup or near beer might become the next big product for your favorite micro — or macro — brewery.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org