The afternoon that Joe Masseria dined on bullets

Ninety years ago, New York Mafia boss was gunned down in a brazen assassination

The tale of Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria’s assassination on April 15, 1931, is one of many gangland legends that have been told, retold and morphed over the decades. It is sometimes hard to distinguish facts from folklore. One thing is certain: We were not there, so we are never going to know precisely the who, what, when and why of this particular hit.

Fortunately we do have reports from law enforcement officers who were eyeing the mobster’s every move (though they were not as clued-in as they thought they were). We also have the accounts of newspaper reporters (albeit often overdramatized narratives). In this case, we also are privy to an insider’s account. While those close to the assassination plot and execution remained mum for life, some critical details were divulged by a man most historians seem to trust for authenticity – Nicola Gentile.

King of wine, fish and booze

Born in Menfi, Agrigento Province, Sicily, in 1886, Joe Masseria emigrated to the United States in 1903. He already had a criminal history in Sicily and quickly inserted himself into New York’s underworld. His reign of power began around 1920, and by the latter ’20s, within the region he ruled, Masseria collected payments from virtually every vendor and controlled a multitude of rackets.

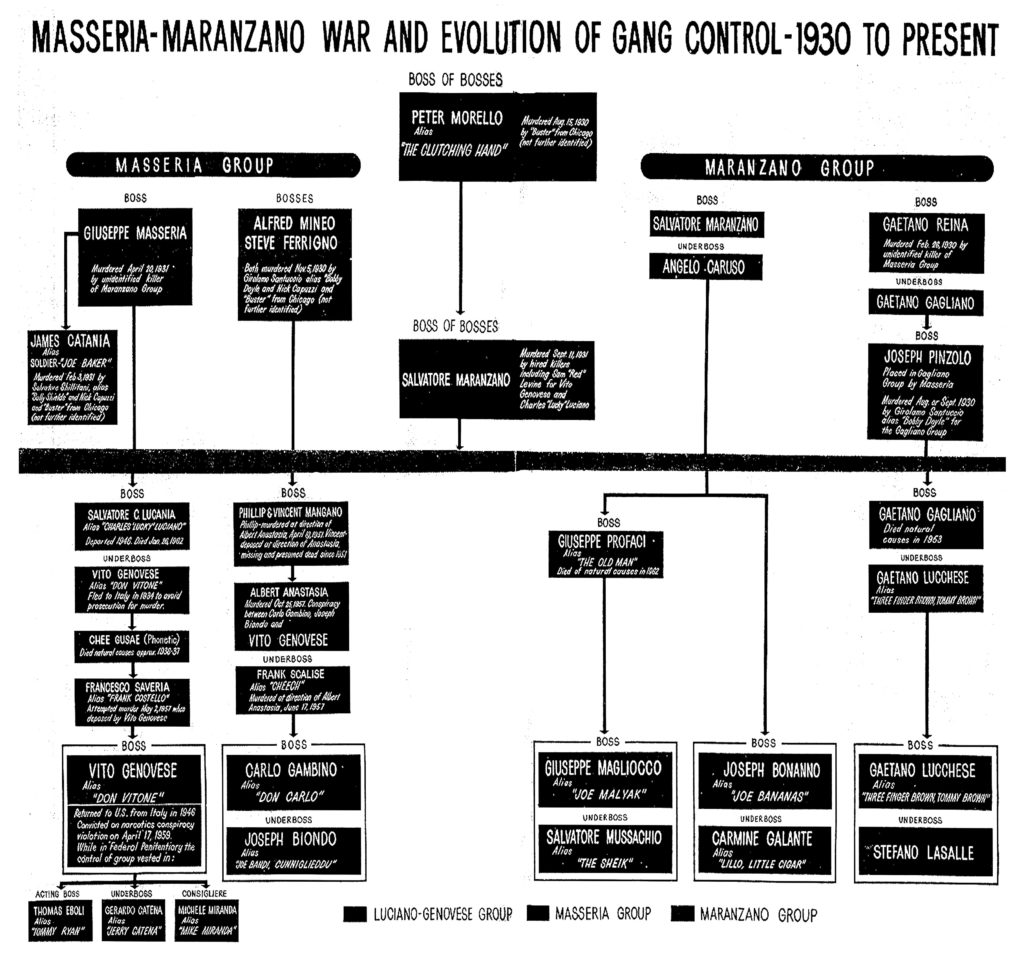

Not unlike his contemporaries, Masseria embraced an old-school idealism, resisted change and always wanted a bigger piece of the pie. The so-called Castellammarese War was the product of Masseria’s angst over a newly positioned Mafioso in Brooklyn – Salvatore Maranzano, who hailed from Castellemmare de Golfo, Sicily. The street war began in 1930 and continued until Masseria’s demise in 1931.

Some historical accounts imply Masseria opposed doing business outside the clan (and this contributed to his downfall at the hands of more progressive subordinates), but that’s not entirely true. For examples, and contrary to some accounts that describe Masseria as being strongly against Jewish or Irish alliances, the facts seem to indicate he was considerably tolerant of other ethnic groups. Masseria himself had counterfeiting interests with Jews, and was aware that some of his closest aides conducted business with men of other ethnicities. One example of this is demonstrated in a widely reported 1930 Miami gambling bust, in which Masseria got pinched along with 18 other players who included not only Italians such as Lucky Luciano, but a number of Jewish gangsters as well, including Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel (using the alias Harry Rosen) and Harry Brown (forever immortalized in the 1932 Chicago arrest photo of Luciano and Meyer Lansky with a couple of Al Capone’s boys).

Still, Masseria represented an outdated mindset, one that could no longer be reasoned with diplomatically. The same was true of his rival Maranzano. The ongoing tit-for-tat killing wreaked havoc not just on the streets but well into the Mafia hierarchy. This was also a time when the definition of “loyalty” became exceedingly unclear.

Sanctioned insurrection

As is almost always the case, Masseria’s downfall was not the result of any single factor. The American organized crime system had plenty of turmoil and dissent, side deals and secretive plots going on at any given time, but the battle between Masseria and Maranzano caused concern even beyond the borders of New York. Maranzano’s war of attrition proved a successful tactic in stripping away Masseria’s strength, and the latter’s own men were ready to defect. Meetings of the Mafia’s elite tried to bring about an end to the bloodshed, but Maranzano consistently manipulated matters to his own advantage. Also at play, on the broader scale, was a natural evolutionary process: The mob was progressing and expanding. Those resistant to change generally don’t last long. Such was the case for Masseria, and, a little down road, for Maranzano as well.

In order to facilitate underworld peace, the consensus turned from diplomacy to the inevitable – one of the two bosses had to go. The final straw, according to the account of Nicola Gentile and with regard specifically to Masseria’s remaining inner circle, was a disagreement over carrying guns. Police had called Masseria in at some point and demanded the violence cease. Still clinging to idealism and holding out hope for eventual peace, Masseria responded by disarming his men. The edict was not warmly received.

“But the boys not being of the same opinion called Al Capone of Chicago, being he was the capo dei decina (Head of Ten), and he was affiliated to the borgata (family) of Joe Masseria. Secretly, they made the decision to kill him (Masseria).” This according to Gentile, vita di capomafia.

Gentile, along with Vito Genovese, Albert Anastasia, Joe Biondo, Vincent Mangano, Paul Ricca (Capone’s No. 2) and others, met often in a hotel room, planning the coup. According to some accounts, Genovese and Luciano met directly with Maranzano and came to a mutual agreement. “Do you know why you are here?” Maranzano asked. The pair nodded confirmation. “Good,” Maranzano said. “I don’t have to tell you what needs to be done.” Before Maranzano excused them, he added, “I’m looking forward to a peaceful Easter.”

After a year’s worth of chaos, collusion and consultation, they chose to depose the weaker of the two embattled bosses, Giuseppe Masseria. Getting him out in the open wasn’t going to be an easy task, but eventually the plotters lured him to a lunch in Coney Island – Nuova Villa Tammaro 2715 W. 15th Street. Masseria arrived in his armored car with two bodyguards. They were led to a table in the back, where another man was already seated. Masseria ordered light, just some bread, wine and coffee. After the foursome was served, owner Gerardo Scarpato instructed his mother-in-law to remain in the kitchen, while he casually “took a walk” from the building.

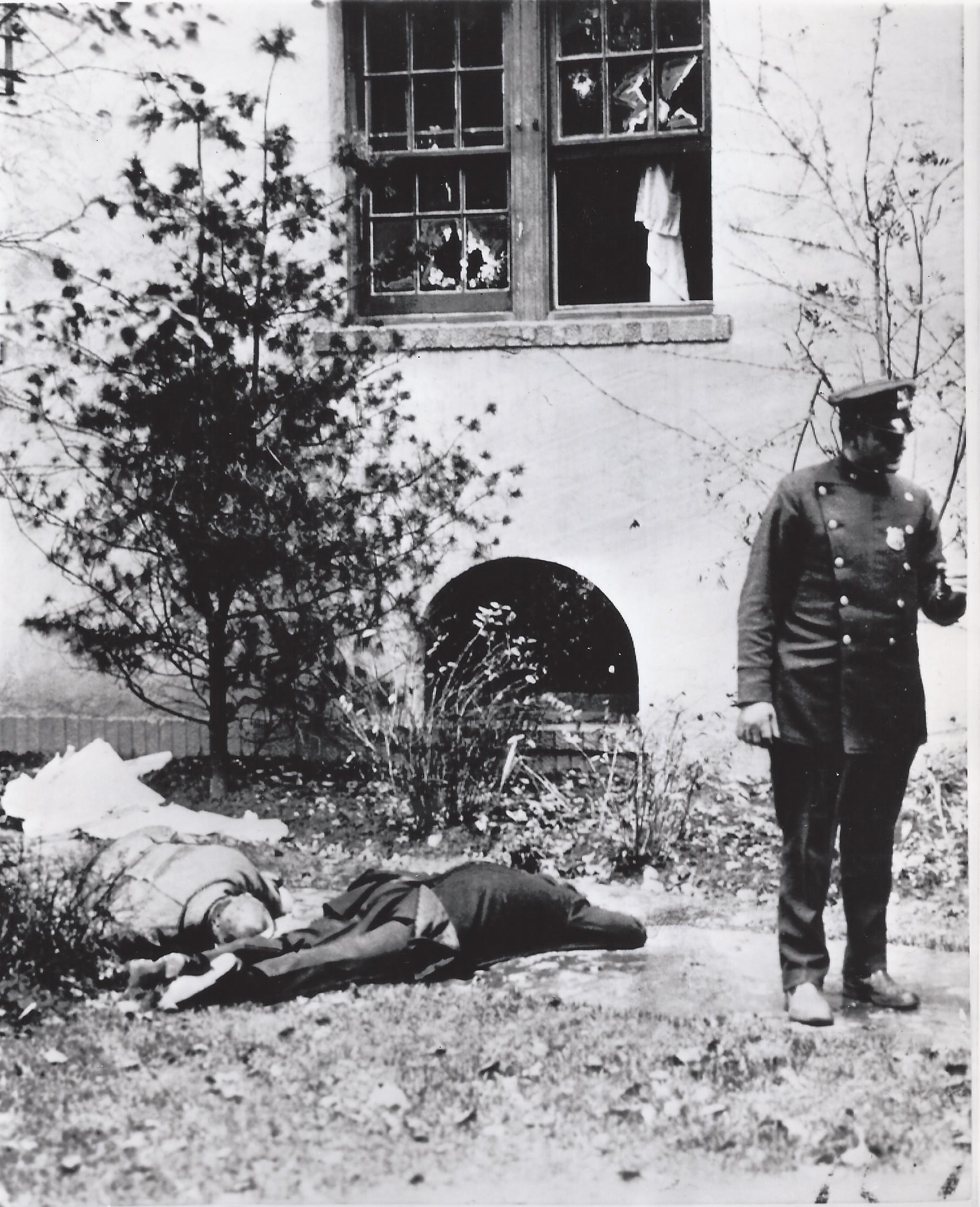

About 3 p.m., Joe the Boss, while engaged in a hand of pinochle, took four bullets to the back, and one to the head. His body slammed into the table, then to the floor. The entourage quickly exited the restaurant and entered waiting getaway vehicles. They left behind a stolen car, several guns, hats and overcoats.

Witness accounts were slim to none, while media reports added flair and the cops considered a number of theories that were perhaps close in some ways yet ultimately way off base in terms of ever achieving legal closure. The accounts echoed the same story – two men approached Masseria from behind and a series of gunshots rang out. The garments left behind did, however, provide some clues, or so the detectives hoped. Suspicion fell on a Chicago connection, also a dope racket, but everyone agreed it was “an inside job.”

Sam Pollacia, a close Masseria associate and owner of one of the leftover coats, was questioned for allegedly being present at the lunch meeting. Of course, he denied being there. Augie Pisano had been seen meeting with the restaurant’s owner, Scarpato, before the murder. Scarpato, when questioned as to why there were no waiters around, stated that everyone was off work, it was “a light day.” Cops also questioned Ciro Terranova who, according to some versions of the legend, served as one of the getaway drivers.

The aftermath

In his memoir, Gentile stated that he and Paul Ricca arrived at Nuovo Villa Tammaro just after the fact. Seeing the heavy police presence, they changed course and rushed over to Luciano’s apartment. While there, Gentile recounted, one of Maranzano’s emissaries, Vincent Troia, arrived. Luciano gave Troia a message to relay back: “Don Vincenzo, tell your compare Maranzano that we have killed Masseria – not to serve him, but for our own personal reasons. Tell him that if he should touch even the hair of even a personal enemy of ours, we will wage war to the end. Tell him that within 24 hours he must give us an affirmative answer for a meeting at a locality which we will pick out.”

As expected, Masseria’s funeral was lavish, complete with a $15,000 bronze casket. The service was held in his Manhattan penthouse apartment at 15 W. 81st Street.

In another blow to the family, several weeks later Masseria’s 19-year-old daughter, Vinitia, succumbed to illness and died. Without missing a beat, the press called it a death from a “broken heart.”

As for restaurateur Gerardo Scarpato, his future looked bleak as well. After the Masseria hit, Scarpato requested to be fingerprinted, just in case something happened. He then took his family on an extended sabbatical to Europe. He returned in June 1932 and took another step that foreshadowed impending doom. Scarpato got tattooed with his name and address on the forearm. That September, his body was found in a burlap bag inside an abandoned car.

Scarpato fell victim to an up-and-coming method of witness elimination: trussing the victim in rope in such a way that struggling brings about strangulation. Incidentally, this tactic was later fine-tuned (by adding icepick punctures) and became the calling card of Brooklyn’s kill-for-hire group Murder Inc. At the same time, investigators turned their attention to Masseria’s former adviser.

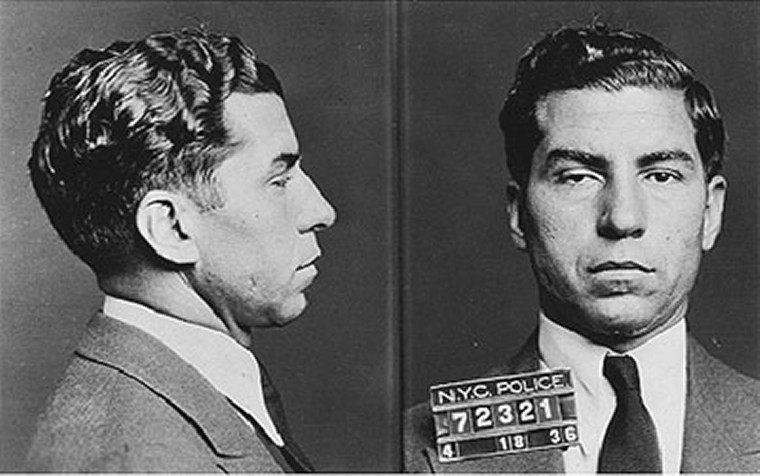

“As part of their investigation, New York police requested Chicago authorities to question the present head of the Sicilian organization, Lucky Luciano, intimate of Ralph Capone and now a threatening factor in New York’s underworld,” the New York Daily News reported on September 12, 1932.

The new reigning overlord, Salvatore Maranzano, would also get his day of reckoning, but that is a story for another day.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Lucky Luciano: Mysterious Tales of a Gangland Legend and Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org