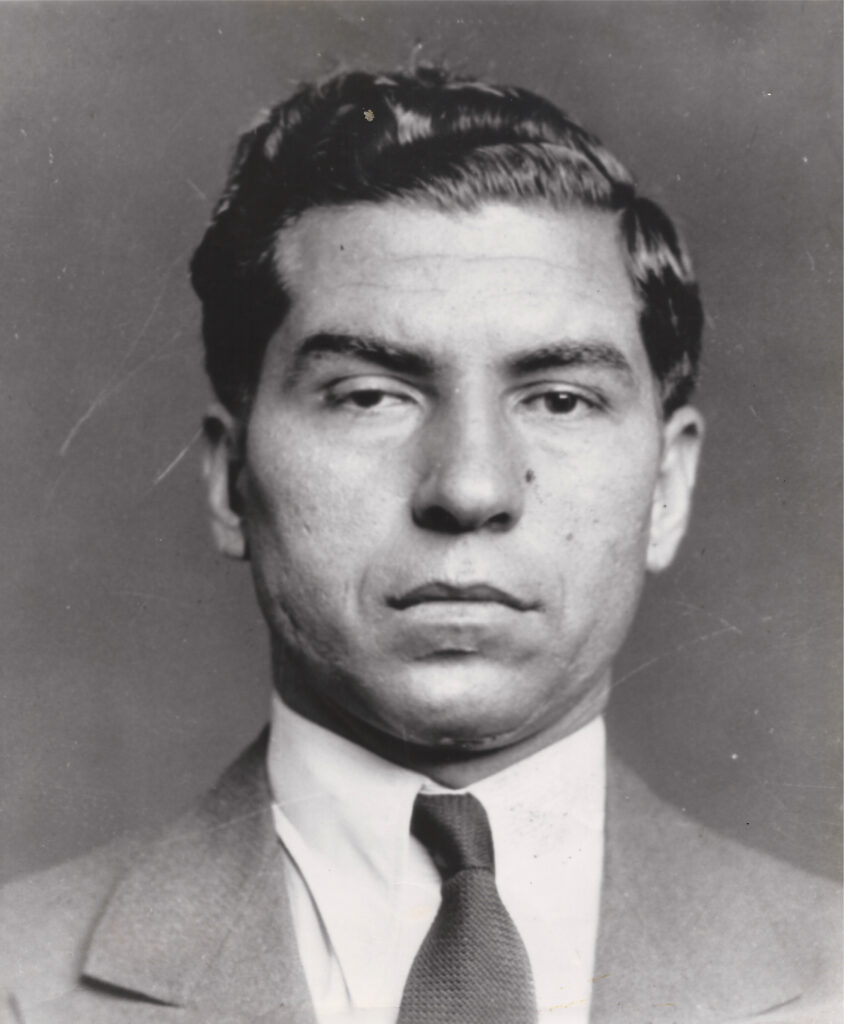

Eighty years ago, Lucky Luciano traded prison for exile

New York governor commuted Mob boss’s sentence on condition of deportation

When New York Governor Thomas Dewey commuted the sentence of imprisoned Mafia boss Charles “Lucky” Luciano 80 years ago, it was widely described as an act of wartime necessity. For Luciano, it proved to be a life sentence of a different kind.

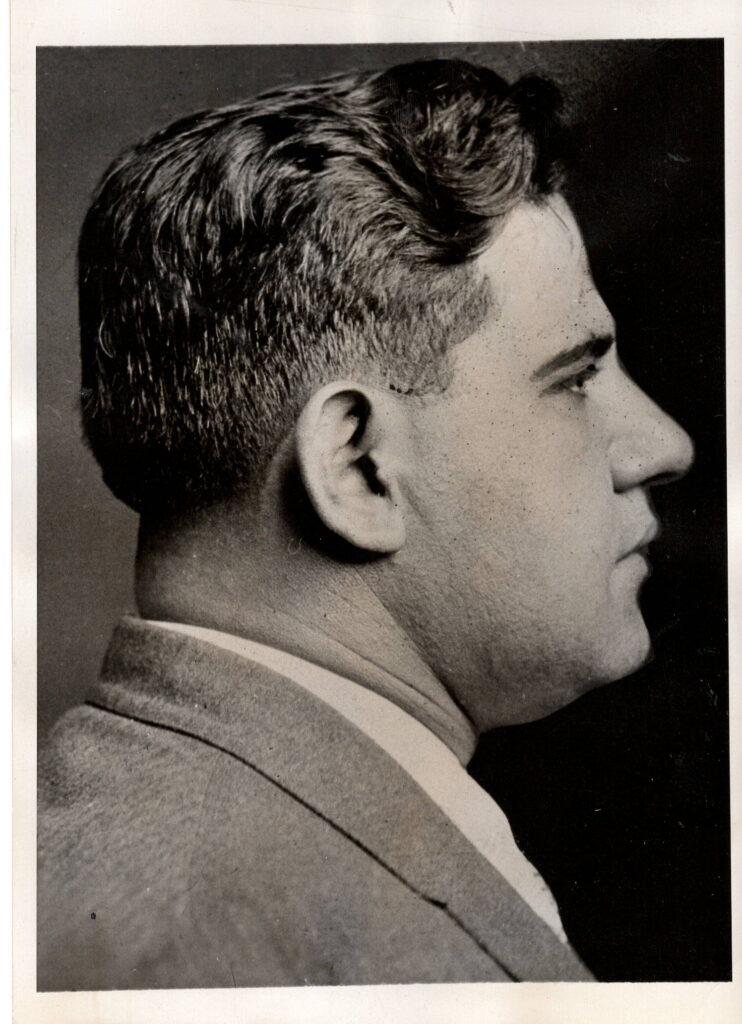

Dewey’s rise to national prominence began in 1935. New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and Governor Herbert Lehman backed the creation of a special prosecutor’s office to confront racketeering and political corruption that conventional law enforcement had failed to contain. Dewey — young, disciplined and relentlessly visible — fit the moment perfectly.

LaGuardia valued Dewey’s independence and understood the political dividends of a successful crusade against organized crime. Dewey, in turn, recognized that high-profile prosecutions could serve both justice and ambition. His office produced arrests, headlines and convictions. Critics soon noted that Dewey appeared as adept at managing public perception as he was at managing cases.

Dewey’s first major fixation was Arthur Flegenheimer, better known as Dutch Schultz. As Dewey’s investigations tightened, Schultz voiced his hostility within the upper reaches of the underworld, proposing to the Mafia’s ruling body, the Commission, that Dewey be eliminated. The idea was briefly entertained — Albert Anastasia is said to have conducted reconnaissance on Dewey’s routines — before the Commission rejected it outright.

When Schultz announced he would proceed regardless, his fate was sealed. The bosses could not tolerate a unilateral act that would invite catastrophic retaliation. Schultz was gunned down in New Jersey in October 1935, undone not by Dewey but by his own recklessness.

As Schultz lay dying, detectives recorded fragments of delirious speech, including references to “The Boss” and “John,” interpreted as nods to Luciano and Chicago mobster Johnny Torrio. Whether meaningful or not, the episode further cemented Luciano’s image as the unseen authority behind the syndicate — and a new target for Dewey.

Dewey’s methods of securing a conviction against Luciano remain hotly debated. Although Dewey was successful in indicting Luciano on prostitution-related charges, it was far from an airtight case, as direct evidence implicating Luciano was in short supply. But the outcome is not disputed. In 1936, Luciano was convicted and sentenced by Judge Philip McCook to 30 to 60 years in prison.

Luciano was briefly housed at Sing Sing prison before being transferred to Dannemora, aka “Little Siberia,” which state officials believed would be most effective in isolating him. There he remained until global events presented an opportunity.

A waterfront at war

Dewey’s prosecutorial fame propelled him into electoral politics. After losing the 1938 gubernatorial race, he won the office in 1942. At the same time, the United States entered a global war that unexpectedly reconnected Dewey with Luciano.

With the New York Harbor vital to the war effort, military officials feared sabotage and espionage along the waterfront — an area long dominated by organized crime. Those fears intensified in February 1942 after the docked USS Lafayette, formerly the French liner Normandie, caught fire and capsized. Though later deemed an accident, the incident accelerated cooperation between the Office of Navy Intelligence and law enforcement.

ONI officers, including Captain Roscoe C. MacFall and Commander Charles Radcliffe Haffenden, consulted Manhattan District Attorney Frank Hogan and Assistant DA Murray Gurfein for access to the underworld. They made contact through Fulton Fish Market boss Joseph “Socks” Lanza, who pointed them toward the most influential incarcerated figure available: Luciano.

Luciano’s prison visits soon included a “who’s who” of Mob figures and attorneys. His influence was quietly acknowledged, if rarely detailed, regarding the New York waterfront (and, later, Sicily during the Allied invasion, dubbed Operation Husky).

The calculation behind commutation

In early January 1946, Dewey acted on a formal recommendation from the New York State Parole Board to commute Luciano’s sentence, with deportation as a condition. The decision was finalized on February 9, setting in motion Luciano’s immediate removal from the United States.

Luciano’s wartime cooperation has often been framed as blackmail or a secret bargain. Historian Thomas Hunt offers a more pragmatic interpretation. Any truly damaging material Luciano possessed, Hunt notes, would likely have surfaced during his appeals. None ever did, and Dewey was well aware that Luciano’s sentence was excessive in the first place.

Instead, Dewey’s decision to commute Luciano’s sentence — on the condition of permanent deportation — represented the most expedient outcome available.

“Dewey’s conditional commutation and deportation allowed him to ensure that [Luciano] was kept out of New York and the rest of the United States permanently,” Hunt explains. “While this is often presented as some sort of win for [Luciano], it actually looks to me like the best possible outcome that Dewey could have hoped for at that moment.”

In February 1946, Luciano was transferred to Sing Sing, then taken to Pier 7 at Bush Terminal in Brooklyn and placed aboard the Laura Keene, bound for Italy.

Dewey was re-elected governor in 1946 and later ran unsuccessfully for president in 1944 and 1948. His upset loss to Harry Truman effectively ended his national ambitions.

Luciano, meanwhile, alternated between resentment and resignation. “Dewey framed me,” he told columnist Earl Wilson in 1949. “But it was politics. He was ordered to do it, and he stooped to it.” He paused before adding, “But I got out of prison under him … so I got nothin’ against him.”

Depending on his mood, Luciano offered varying assessments of Dewey over the years. “I almost made Dewey president,” he boasted to columnist Leonard Lyons in 1958. “And I almost made Kefauver vice president.”

The commutation resurfaced publicly during the Kefauver Committee hearings of 1950–51, when investigators scrutinized organized crime’s reach into politics. Dewey did not testify, but Commander Haffenden did, later admitting he may have overstated Luciano’s wartime value: “I used the word ‘great,’ which was probably over-evaluating it.”

In 1951, the Gannett News Service, citing what it described as a reliable source within Dewey’s inner circle, outlined the governor’s reasoning for commuting Luciano’s sentence. According to the report, the decision rested on three points:

- The commutation was recommended unanimously by the Parole Board.

- Luciano had already served 10 years in prison, representing the first of the consecutive terms imposed at sentencing.

- The commutation of the minimum sentence was contingent upon permanent banishment from the United States.

“There is no mystery about the case,” Dewey said. “I spent 18 months putting Luciano in jail. The commutation was handled in the same way those matters have been handled by all governors of New York in recent years, with one exception.”

Luciano rarely discussed the specifics of his wartime assistance, preferring generalities colored by mood. Speaking to a Reuters reporter in 1949, his tone shifted from resignation to melancholy. “In 1946, I was pardoned and sent to Italy,” Luciano said. “America wanted to thank me in this way — but at the same time she said, ‘Goodbye, Lucky. Let’s be friends — at a distance.’”

Christian Cipollini is an organized crime historian and the award-winning author and creator of the comic book series LUCKY, based on the true story of Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org