One hundred years ago: Murder of ‘Big Jim’ Colosimo spawned one of the most powerful crime syndicates in American history – the Chicago Outfit

Colosimo’s demise also launched legendary crime careers of Johnny Torrio and Al Capone

Three weeks after his marriage to the beautiful singer Dale Winter, James Colosimo remained giddy, and nervous. Known as “Big Jim” or “Diamond Jim” for his obsession with the gems, Colosimo reigned as boss of a whorehouse empire in Chicago’s Levee vice district. Celebrities, powerful pols and opera performers crowded his Colosimo’s restaurant, with a café-cabaret and separate late-night fine dining room.

On May 11, 1920, Colosimo and Winter set a date for dinner in the city’s fashionable and exclusive Loop area, along the shore of Lake Michigan. But Colosimo phoned Winter to tell her he’d be late, due to a sudden appointment. “Angel, just got a call,” he said to her. “Gotta meet a guy at the restaurant. It’s important.”

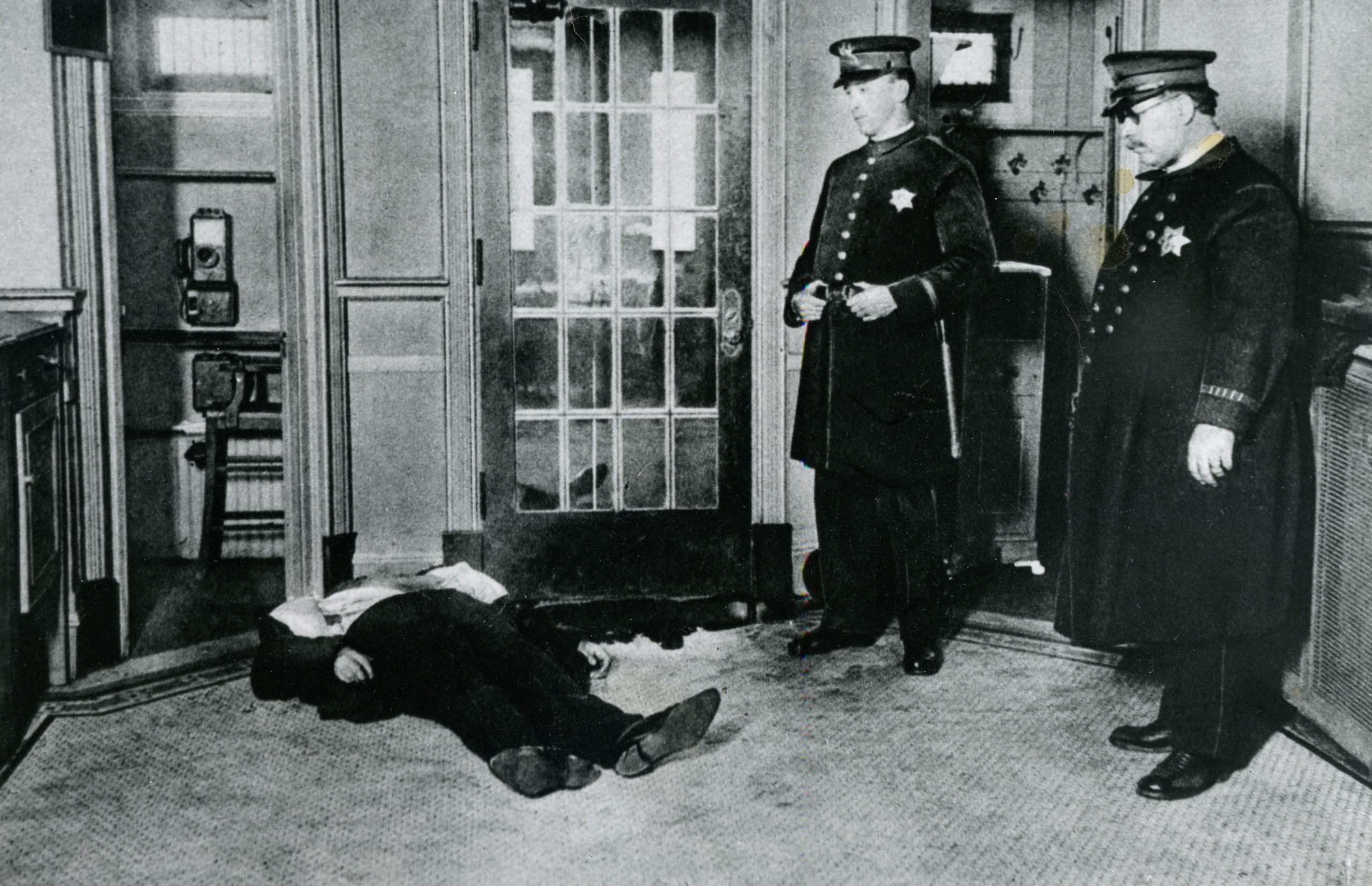

Colosimo had his chauffer drive him in his Pierce-Arrow to the restaurant that afternoon. Inside the still-closed restaurant, he asked a porter, Joe Gabrela, if he’d seen a man looking for him. Gabrela said no. Colosimo entered his office. Soon, Gabrela noticed a man in the dining room. “Mr. Colosimo’s in the office,” he told the man before leaving the room. Then the restaurant’s accountant noticed Colosimo exit the office. About a minute later, he heard a gunshot.

Colosimo had just peered out a windowed door to the large foyer of his café toward the street, when a gunman strode behind him and fired a .38-caliber revolver into the base of his brain, killing him instantly. The suspect fled, but Gabrela provided police with a detailed description. Chicago Police, acting on tips, shrewdly theorized that Brooklyn mobster-killer Frankie Yale did it. Gabrela did identify Yale in a photo lineup. But as things often wound up in gangdom in those days, his fear got the best of him. Taken to view a live police lineup in New York that included Yale, Gabrela declined to finger him. Practically everyone knew it was Yale, but lack of evidence meant no murder charges filed against anyone.

Johnny Torrio, Colosimo’s righthand man and Yale’s former saloon partner in Brooklyn, leapt into action. He organized an extravagant funeral for his dead boss that would serve as the template for future over-the-top, flowery send-offs for murdered mobsters of the 1920s. In a tribute to Colosimo’s political influence, mourners at the funeral inside his home included the all-powerful First Ward alderman and Cook County Democratic committee member Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna, the second First Ward alderman “Bathhouse” John Coughlin, several other aldermen, a couple members of Congress, a state legislator and a few judges. About 5,000 people, some holding banners for the Democratic Party and street laborers union, trailed a hearse carrying Colosimo’s body in a $7,500 silver and mahogany casket to Oakwood Cemetery.

When people outside Colosimo’s brownstone watched Torrio enter Kenna’s waiting car, they realized who had moved in as Big Jim’s heir apparent in the First Ward. The Chicago Outfit was born.

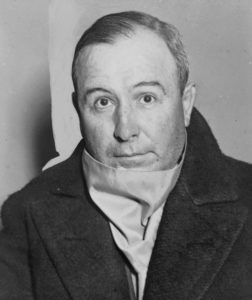

Torrio most surely planned Colosimo’s assassination, enlisting Yale, his friend, former business partner and experienced hitman. His motivation to off his boss, acknowledged by history, came from his understanding that Prohibition, effective that January 17, clearly offered massive profits, based on his and Colosimo’s existing model of payoffs to police and local office holders to look the other way from Colosimo’s many prostitution houses in the area. Torrio read that the federal Prohibition enforcement agents would be political appointees, not subject to U.S. civil service rules. In other words, low-paid, low-skilled hacks, ripe for bribery and inattention to liquor smuggling.

But Colosimo, still in rapture with his new bride, disagreed with Torrio, fearing the prospect of federal law enforcement without the protection he was used to. Better to keep things the way they are locally, in the Levee and Loop, he thought. He nixed Torrio’s idea to make a major racket out of bootlegging.

However, it is rarely reported that Colosimo did in fact approve Torrio’s scheme to reopen closed breweries to make and sell illegal, real beer to underground merchants and barkeeps in Chicago. Earlier, before Prohibition, Colosimo invested $25,000 in a brewery operated by one of his saloon owners, Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik (one author claimed Guzik garnered his nickname for serving beer with his thumb in the stein). Still, this didn’t go far enough for Torrio. Just as he convinced Colosimo to expand the brothel business to the rising suburbs and towns bordering Chicago, he rightly predicted that unbridled bootlegging of beer and hard liquor would produce far more money — millions. Colosimo was dead set against going much beyond prostitution in Chicago and the suburbs, and his popular restaurant. For Torrio, to build this new domain, his shortsighted boss had to go.

Colosimo, born in 1878 in Palermo, Sicily, moved with his parents to the Windy City at age 1. He would not have reached his height as top pimp in Chicago – the nation’s brothel capital – without Hinky Dink Kenna’s well-paid protection. Hinky Dink and Bathhouse Coughlin represented the First Ward, when wards had two city alderman each, from the 1890s to the early 1920s. Two masters of influence and graft, Hinky Dink, thin, stoic and not quite five feet tall, and the floppish, flamboyant Coughlin, helped themselves to payments, not only from the vice businesses in the Levee, but on everything awarded by the city council in their ward – licenses, permits and utilities needed for hotels, banks, shops and clubs in the Loop as well as federal and state offices, the police, courts and jails. Colosimo, as Torrio after him, served at the pleasure of Kenna as his vice gang underlings and made sure he received his cut of the proceeds. Kenna let the illicit gambling operators and brothel madams run as long as they, as precinct captains, delivered him the votes to win elections.

Colosimo’s links to Hinky Dink started in the 1890s when Jim was an engaging young bootblack inside Kenna’s rowdy Workingman’s Exchange saloon. Kenna took a liking to the kid and later arranged for a city patronage job as a street cleaner. Colosimo ingratiated himself with Italian immigrants and got them to support Kenna. The boss in return promoted Colosimo to street cleaning supervisor. Colosimo organized his Italian men into a street cleaners union.

By the early 1900s, prosperous Chicago had been a bastion of illegal but tolerated prostitution for decades. Colosimo, with Kenna’s approval, made the move to the brothel business by marrying Victoria Moresco, a madam – six years older than Big Jim — of a pair of dollar-a-go whorehouses. Kenna elevated him to precinct captain to deliver the Italians to the polls. Colosimo was second only to Ike Bloom, the First Ward’s vice money bagman, in political power, under bosses Kenna and Coughlin.

In 1909, the dangers of Chicago vice life intruded on Colosimo’s rising stardom. Black Hand extortionists, by letter and then at gunpoint, demanded Colosimo pay them $50,000. He needed a bodyguard. Victoria knew someone who might be right for it – her cousin, Johnny Torrio (born in southern Italy in 1882), who co-owned a saloon called the Harvard Inn in Coney Island, Brooklyn, with Frankie Yale. They offered to pay Johnny’s expenses and put him up in their Chicago brownstone. Torrio, weary of years of gang wars in the New York area, decided to make the move, and sold his share in the Harvard to Yale.

Unsure of the calm, squat, chubby Torrio, Colosimo told him about his problem. Torrio, a veteran Black Hand-style extortionist himself in Brooklyn, assured Big Jim he had it covered. Driving a horse-drawn carriage with two Colosimo gunmen hiding inside, he lured the three extortionists one night with the promise of a payment. The gunmen stood up, shot and killed two of them and mortally wounded the third. Colosimo hired Torrio as his bodyguard. As time went by, Colosimo noticed Torrio’s talent for finances and leadership and delegated responsibility for managing prostitution houses to him as a “male madam.”

In the 1910s, Colosimo rose to vice boss and Kenna’s collector in the First Ward, thanks both to Hinky Dink’s sway with police, judges and prosecutors, and Torrio’s business acumen. With the Loop district’s thriving businesses and fancy residences, the First Ward developed into perhaps the richest area in the whole Midwest.

For Torrio’s headquarters, Colosimo bought a four-story building at 2222 S. Wabash Avenue. Torrio opened an office, a saloon – the Four Deuces – a gambling house and fourth-floor brothel. While there, his old friend Frankie Yale sent him a letter, asking if he could give a 19-year-old roustabout bar worker of his, Alphonse Capone, a job. The teen cut up a man in a fight and needed to leave New York. Torrio made Capone his front door bouncer and then, after seeing his violent side, his bodyguard.

By his death in 1920, Colosimo had unknowingly fathered the shell of an organization that Torrio, and Capone who succeeded Torrio in 1925, would transform into the Outfit, one of the most powerful crime syndicates in American history.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org