Tentacles of organized crime once had firm grip on Japanese politics

Assassination of Shinzo Abe one year ago grew out of connections to yakuza and Unification Church

The yakuza, Japan’s premier organized crime group, is becoming more visible in modern pop culture. From HBO’s Tokyo Vice to Sega’s popular Yakuza game series, the influence of these mobsters has moved beyond Japan’s borders onto the world stage. However, the yakuza are not new players in the global network of organized crime. For decades, they have been involved in criminal activity worldwide, including drug trafficking and prostitution, even reaching the shores of the United States. But the yakuza have been running rackets in Japan for centuries.

Japanese organized crime goes back to the 17th century, when roaming bands of peddlers and gamblers spread their trade along the highways of Japan’s feudal society. In fact, one origin of their name is attributed to a losing hand in a popular card game: 8-9-3, or ya-ku-sa. However, modern yakuza originated among the ultranationalists who perpetrated the imperialism that led to war in the Pacific Theater in the 1940s. Some early yakuza bosses were part of the military and political leadership imprisoned as war criminals following the end of the conflict. Since the U.S. occupation, the yakuza have become increasingly involved with government leaders, including as high up as the prime minister.

Despite their past presence in politics, Japanese law enforcement and government bureaucrats have worked tirelessly over the last three decades to expel yakuza influence from their ranks. Yet the footprint of the yakuza continues to be seen in Japanese affairs. Yakuza leaders and their associates have allied with East Asian criminal organizations and right-wing groups that remain in Japan today. One of these associations, with the Unification Church, ultimately led to the assassination of one of Japan’s top officials.

On July 8, 2022, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stood on a podium giving a speech in Nara, Japan. Testuya Yamagami, an unemployed 41-year-old, approached Abe from behind with a makeshift gun made from wood and metal pipes and shot Abe in the back. Five hours later, Abe was pronounced dead at Nara Medical University Hospital.

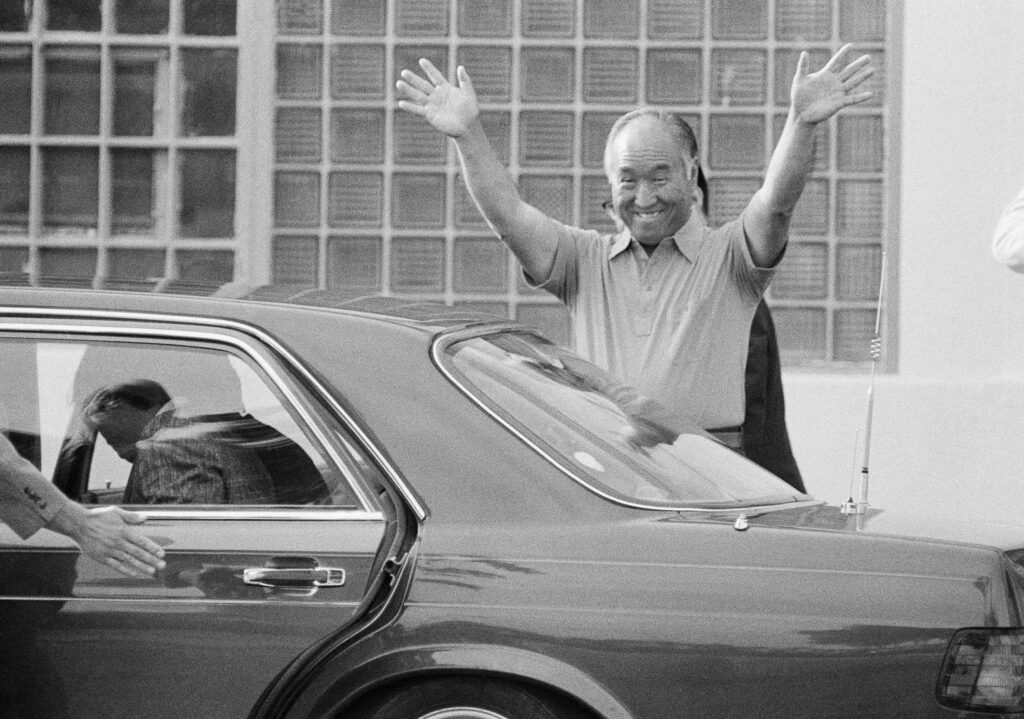

Yamagami confessed to investigators that his motive for killing the emeritus prime minister was Abe’s ties to the Unification Church. The Unification Church is a Korean religious organization started in 1954 by self-proclaimed messiah Sun Myung Moon. Often called the “Moonies,” the organization is seen by many as a cult. Yamagami told investigators that his mother donated more than 100 million yen (about $735,000) to the church, bringing financial ruin to their family.

Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party denies any ties to the church, and any current politician with ties to the church has either resigned or been removed since the assassination. However, a look into Japan’s postwar prime ministers – including Abe’s grandfather Nobusuke Kishi – reveals many ties with far-right nationalist organizations, including the Unification Church and the yakuza.

After Japan’s surrender brought World War II to a close in 1945, General Douglas MacArthur led the U.S. occupation to rebuild a devastated Japan. The occupying forces repurposed Tokyo’s Sugamo prison to house “Class A” war criminals awaiting trial. However, some inmates were released shortly afterward thanks to shifting priorities in the American intelligence community. Japan’s pre-war extreme right politics proved useful in combating communist ideologies spreading from Russia and China. One of these inmates was Yoshio Kodama, who before the war organized spies in China and created a smuggling operation to sell stolen Chinese goods in Japan for substantial profits. His intelligence network in communist China made him an ally of the CIA. Meanwhile, Kodama wasn’t the only Sugamo inmate with a bright future in Japan’s underworld.

Kodama’s cellmate was Ryoichi Sasakawa, who along with Kodama were known as behind-the-scenes power fixers called kuromaku (literally meaning “black curtain,” a reference to the hidden wirepullers controlling the black curtains in traditional Kabuki theater). Upon his release, Sasakawa built a speedboat gambling empire and became one of the world’s richest men. He and Kodama used their enormous wealth to influence politics, leading to the formation of the Liberal Democratic Party, which still dominates Japanese politics today. Through considerable campaign donations and the CIA’s help, the duo had their pick for LDP leadership. In 1957, another former Sugamo kuromaku and Shinzo Abe’s grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, became the prime minister.

With the CIA’s support, Kishi and the kuromaku garnered the support of far-right nationalist political parties. Many of these deceptively named “political parties” were, in fact, yakuza gangs. When the fledgling National Police Agency began cracking down on organized crime, the yakuza gangs that ruled the postwar underworld rebranded themselves as rightist organizations. The yakuza were frequently called on to stifle any stirring dissent from leftist groups.

Their number came up when U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower was planning a state visit to Japan amid renegotiations of the U.S.-Japan Security Pact. While the LDP was on board with the new arrangement, socialist groups opposed the deal, including the People’s Council for Preventing Revision of the Security Treaty, “Ampo” for short.

The LDP alone was unable to amass the security necessary to prevent leftist protesters from interfering with Eisenhower’s visit, so they turned to Yoshio Kodama. Kodama, along with Ryoichi Sasakawa and others, organized Zen Ai Kaigi, the All-Japan Council of Patriotic Organizations. The federation of gangs included in its ranks a veritable rogues’ gallery of yakuza bosses. Among them were Kakuji Inagawa, founder of today’s third-largest yakuza group Inagawa-kai; Yoshimitsu Sekigami, fourth chairman of the second-largest group Sumiyoshi-kai; and Kinosuke Ozu, dubbed “Tokyo’s Own Al Capone” by the Saturday Evening Post. Altogether, Zen Ai Kaigi’s forces numbered 38,000 strong. Eisenhower’s invitation was withdrawn, however, after a brawl broke out between Ampo demonstrators and Kodama’s thugs, resulting in serious injuries and one death.

Even though the security pact went through, Nobusuke Kishi resigned in disgrace after the aborted visit. Shortly after, Zen Ai Kaigi dissolved, yet the yakuza retained its connections with Japanese political elites. Kodama and Sasakawa continued to mediate between yakuza groups, and Kodama continued working behind the scenes with the yakuza and the LDP until a major scandal erupted in 1976.

Starting in 1958, Kodama began lobbying on behalf of Lockheed Aircraft Corporation to convince Japanese airlines to buy its airplanes. Over the next two decades, Lockheed spent more than $12.6 million on bribes of Japanese politicians, including a prime minister, Kakuei Tanaka. After this came to light in a 1976 U.S. Senate hearing, the Lockheed scandal became Japan’s Watergate. Kodama’s career was finished, and he was ostracized by the nation. In the aftermath, Kodama suffered a stroke and never returned to organized crime. The culmination of public outrage was demonstrated through the final act of ultranationalist admirer and pornographic film actor Mitsuyasu Maeno. In an over-the-top attempt to assassinate Kodama, Maeno rented a Piper Cherokee plane from a Tokyo airport and crashed it kamikaze style into Kodama’s residence, barely missing the bedridden godfather.

While Kodama was entrenched in the world of bribing politicians, the other kuromaku were forming their own connections. A self-described fascist and devotee of Benito Mussolini, Ryoichi Sasakawa looked beyond Japan’s border for ultranationalist allies. Sun Myung Moon, founder of the Unification Church, was one such ally. In 1954, Moon started his church, famous for its mass wedding ceremonies, and in his autobiography stated that he needed to “go to Japan and America so that I can let the world know the greatness of the Korean people.” In 1958, the Unification Church established a Japanese branch. Sasakawa became an adviser to the branch in 1963. The two became close friends and together formed the International Federation for Victory over Communism, also called Shokyo Rengo, and Sasakawa became its president. Blaming communist China for forcing his resignation, Nobusuke Kishi found common ground with Sasakawa and Moon and was a regular at Unification Church events.

After Kishi’s death in 1987, his son-in-law, Shintaro Abe, became secretary-general of the LDP. Shintaro continued where Kishi left off in supporting Shokyo Rengo and, by extension, the Unification Church. He reportedly encouraged his party’s politicians to accept support and funding from the church. After Shintaro’s defeat in his run for prime minister, Moon was quoted as saying, “Anyone who wants to become prime minister in Japan needs my support. Abe should have become prime minister.” Picking up where his father left off, Shinzo Abe became prime minister of Japan, first in 2006 and later in 2012. As prime minister, Shinzo continued his predecessors’ trends of associating with organizations linked to the Unification Church and Ryoichi Sasakawa.

In the 1980s, the Unification Church’s manipulative means of scamming money from victims, called reikan shoho or psychic marketing, increasingly became a concern among left-leaning Japanese politicians. Even today, targets of these scams are convinced that if they don’t donate to the church, they and their kin will be cursed in the afterlife. Unification Church swindlers sold pottery and other “good luck” charms to their victims, claiming the items would break the spells damning their deceased relatives. These are the same schemes that cheated the mother of Abe assassin Tetsuya Yamagami out of hundreds of thousands of dollars. This spiritual extortion is right out of the yakuza playbook, and ultimately led to the fatal shooting of Shinzo Abe. With his death, the Unification Church’s grasp on Japanese politics has all but disintegrated after the purge of all church-affiliated Dietmen.

A new dawn has emerged in Japan’s relationship with far-right criminal groups. While historically Japan’s politicians have maintained a cozy relationship with organized crime, that is not the case today. First in 1992 and then in 2011, Japanese legislators passed strict anti-yakuza laws and exclusion ordinances that have crippled the gangs’ ability to openly engage in Japanese society. Yakuza are now banned from opening bank accounts, signing property contracts and, most recently, driving on toll roads. According to a recent report from the National Police Agency, yakuza membership has dwindled from 87,000 in 2006 to 22,400 in 2022. While Japan has seen many successes in expunging yakuza elements from society, reminders of their infiltration appear from time to time. In 2008, a tabloid in Japan published a photo of Shinzo Abe and then-Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee posing for a photo with Icchu Nagamoto, a financial broker for the Yamaguchi-gumi yakuza group. Despite his grandfather’s connections, Abe vehemently denied any connections to organized crime.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org