The hit that could have sunk Las Vegas

Sixty years ago, Frank Costello survived an assassination attempt ordered by a rival New York mobster

On May 2, 1957, Frank Costello thought he had problems, but he had no idea. He was appealing a five-year prison sentence for federal income tax evasion (for which he had already served nearly a year) and decided to enjoy a dinner out with his wife and a few close friends. But befitting a man the press had dubbed the “boss of racketeers,” he had pressing business, so rather than stay out for drinks he caught a cab to his apartment at 115 Central Park West.

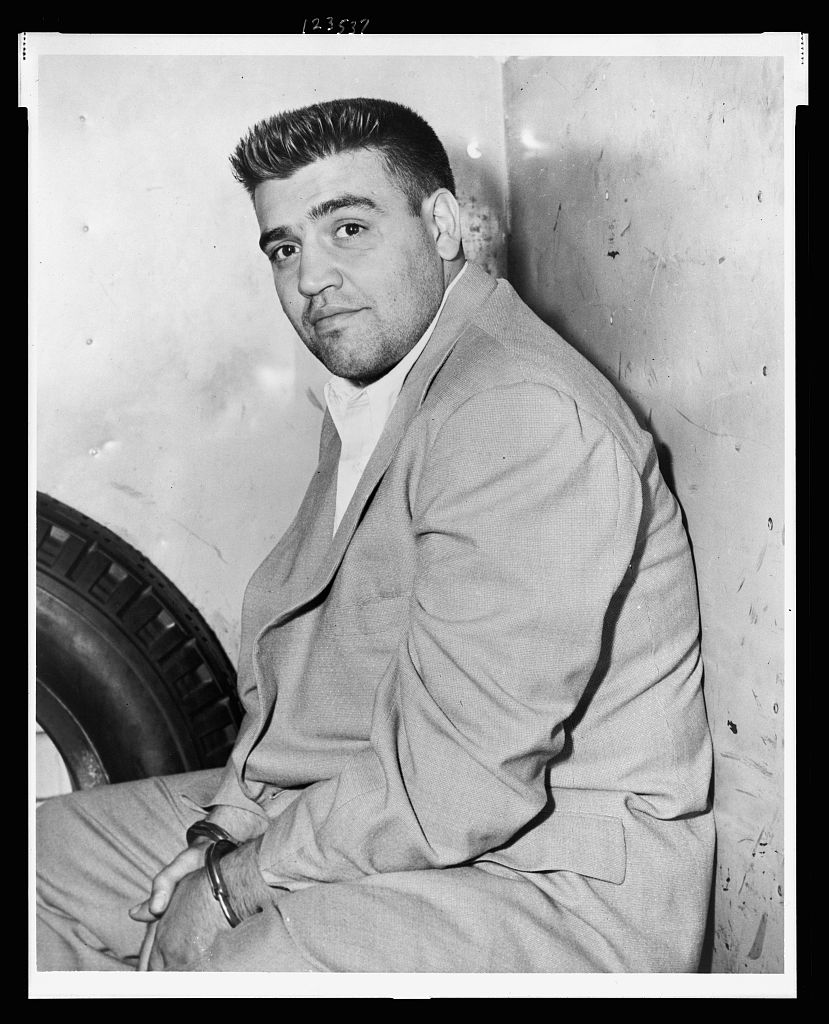

As his cab pulled up to the building, a black Cadillac pulled in behind it. A large man jumped out of the car, followed Costello into the building’s lobby and fired a single shot at his head. Costello crumpled to a leather couch, bleeding, as the gunman raced back to his waiting car, which vanished into the streets of Manhattan.

It was, however, just a flesh wound. Costello was rushed to Roosevelt Hospital, where doctors confirmed that, amazingly, the bullet had only curved around his skull from his right ear to his neck and exited without causing serious damage. After being released, Costello was taken to the West 54th Street police station, where he was questioned to little success. Costello claimed to not only have not gotten a look at the man who had gunned him down, but not to have heard a shot at all.

Doorman Norvel Keith was slightly more helpful — he described a stocky, six-foot-tall assailant. Yet Costello, who had been fighting a variety of charges for most of the 1950s, refused to cooperate even superficially with the police investigation into what detectives agreed was an attempted assassination.

“I don’t have an enemy in the world,” the raspy-voiced gangster told police. As he continued to keep mum, Chief of Detectives James Leggett got frustrated. He had 66 detectives on the case at considerable cost, and knew that Costello knew who had shot him.

While the police eventually did charge Vincent “Chin” Gigante with the shooting (and, in all likelihood, they had the right man), Costello refused to testify against his would-be assassin, who was acquitted. Gigante went on to have one of the most storied careers in organized crime, running the Genovese crime family for more than two decades while pretending to be insane. Costello, by contrast, announced his retirement, a decision likely hastened by the execution of friend Albert Anastasia that October. It is believed that the busted Apalachin meeting of November 1957 was a Mafia summit to sort out the new underworld order in the wake of Costello’s stepping down. Had Gigante succeeded, or not carried out his reputed orders from his boss, Vito Genovese, much of organized crime history might have turned out differently.

Even more interesting, the attempted hit had a direct Las Vegas connection. As Costello was being treated for his wound, police searching his clothing turned up a handwritten memo. It was nothing if not cryptic. “Gross casino wins as of 4-26-57: $651,284. Casino wins less markers $434,595.00 Slot wins $62,844,” with money paid to “Mike,” “Jake,” “L.,” and “H” specified.

Costello refused to disclose anything about the note — its meaning or author — to investigators or a grand jury. When he politely refused Judge Jacob Gould Shurman’s demand to be more forthcoming, Costello was sentenced to 30 days in prison. He was immediately remanded to the Tombs, where he served 15 days before his release.

Working with Nevada investigators, however, New York detectives were able to put the pieces together without Costello’s help. The figures matched to the decimal point the casino win at the Tropicana, which had opened on April 3.

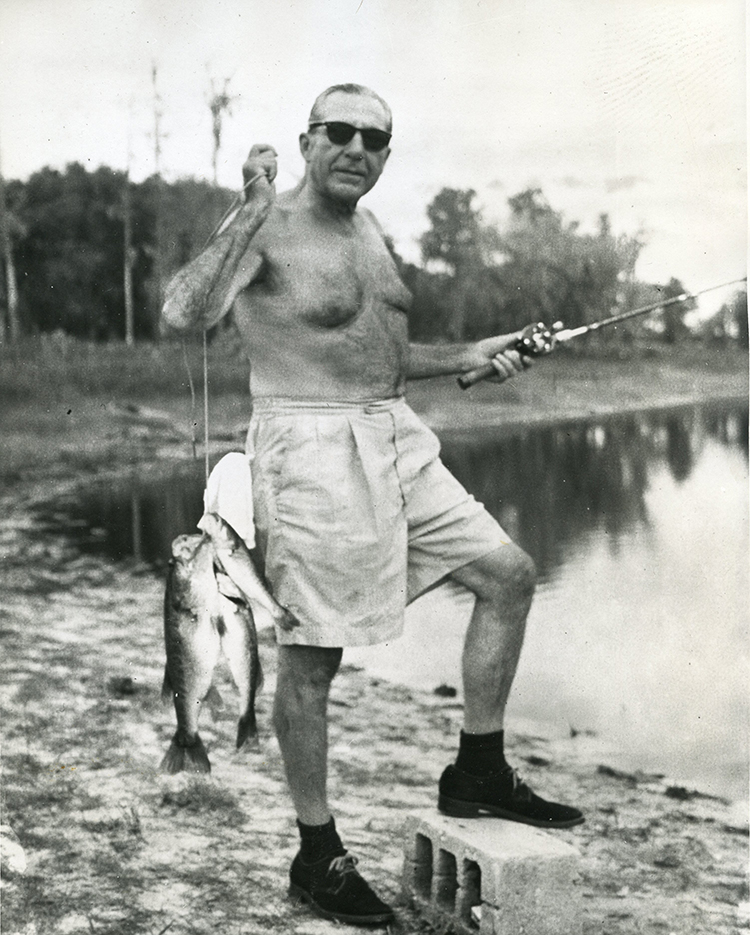

It didn’t take Sherlock Holmes to unravel the connection between the Tropicana and Costello. The casino was developed in part by “Dandy” Phil Kastel, who had partnered with Costello in several gambling operations (including New Orleans’ Beverly Club) and who boasted of his enduring friendship with the embattled Mafia boss. While never licensed to operate the Tropicana, he had been the prime mover behind its design and had invested substantially in the casino.

Potentially, Costello’s note could have been a death sentence for Nevada gaming. Since the advent of the Kefauver Committee in 1950, many in Congress had insisted that Nevada’s casinos were thinly disguised fronts for some of the most vicious criminals in America. The state’s leaders countered that, while it had to some degree had an open-door policy in the past, it had since cleaned house and there was minimal, if any, organized crime influence on its casino industry.

The Costello note gave the lie to that supposed truth. The implications were disturbing. If a man of Costello’s stature kept such close tabs on the accounting at the Tropicana, organized crime clearly had a significant presence in Las Vegas.

That wouldn’t do. The Nevada Gaming Control Board traced the Costello link to two “rogue” employees: executive director Louis Lederer and cashier Michael Tanico. The pair promptly left the Tropicana. Their departures, combined with the casino’s announced intent to repay Kastel’s investment, satisfied the powers that be that the Tropicana would, in the future, be as clean as its neighbors on the Strip.

Contrary to popular wisdom, the Gaming Control Board did not tab J. Kell Houssels with redeeming the Tropicana. Houssels was already a 6 percent owner of the casino and its inaugural manager. At the Tropicana’s opening his experience was hailed as one of the new property’s best advantages. He actually sold his interest later in 1957 and left the company. It was only after a series of financial reversals in 1958 that forced the casino to close that he returned.

And that, too, is an interesting story. Hours after the casino closed, Houssels arrived with a shopping bag crammed with cash. On the strength of his excellent reputation (he had been involved in Nevada gaming since 1930), gaming authorities permitted him to reopen the casino, of which he became the majority owner the following year. The entire process raises some questions. Houssels’ rectitude and skill as a manager were, at the time and more so later, taken as an article of faith by casino regulators and the general public. Yet he had been casino manager when Kastel and Lederer were reportedly skimming for Costello. For this to happen, either Houssels was aware of the operation or ignorant of it; one indicts his integrity, the other his aptitude.

But those kinds of hard questions are rarely asked and less frequently answered. Houssels did successfully run the Tropicana for more than a decade, which, combined with his long history in the business and an excellent record of public philanthropy, burnished his reputation as a straight shooter. And, to be honest, without Costello’s apparent backing, there might not have been a Tropicana at all.

Costello’s shooting, if nothing else, demonstrates how a seemingly innocuous article — in this case a handwritten note — can have tremendous implications.

David G. Schwartz, author of several books on Las Vegas gaming history, is director of the Center for Gaming Research and teaches history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org