Organized crime runs rampant in Latin America

Government corruption allows criminal rackets to flourish

In the United States, organized crime groups steal about $66 billion from retail, cargo, auto and jewelry businesses each year. There are an estimated 3,000 active Mob members in New York, Philadelphia and New Jersey, including remnants of the decades-old Gambino, Bonanno and Lucchese crime families, still steeped in illegal gambling, extortion, loansharking, narcotic sales, armed robbery and murder. And the United States is among the largest markets for international traffickers of cocaine, heroin and other drugs.

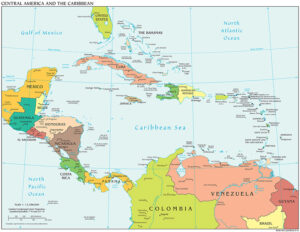

But all of that pales in comparison to the deep influence of organized crime – and the political corruption it fosters – south of the U.S. border in the nations of Latin America – Mexico, Central and South America. Recently, the Mexico-based Citizens Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice released a study concluding that 43 of the 50 deadliest urban areas in the world are in Latin America, with Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, seen as the most dangerous city with 130 homicides per 100,000 people. Acapulco, Mexico, was second.

But all of that pales in comparison to the deep influence of organized crime – and the political corruption it fosters – south of the U.S. border in the nations of Latin America – Mexico, Central and South America. Recently, the Mexico-based Citizens Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice released a study concluding that 43 of the 50 deadliest urban areas in the world are in Latin America, with Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, seen as the most dangerous city with 130 homicides per 100,000 people. Acapulco, Mexico, was second.

Stories about the power wielded by organized crime groups in Latin America at times sound too incredible to be true. They reveal how pervasive and lethal they are, and the brazen lengths some elected leaders are willing to go to cooperate with them to enrich themselves. Drug trafficking groups are so overwhelming, the billions of dollars such a potent factor in politics and government, that the war against organized crime in Latin America appears intractable, unwinnable, permanent. But the stories from that huge region also show that despite the widespread bribery and corruption, determined and honest prosecutors, law enforcers, journalists – and American officials — can and do contribute to winning many of the battles, and at least exposing the perpetrators.

Here is a summary of some of the most egregious examples of how organized crime groups have recently plagued the people, governments and institutions of four Latin American nations: Mexico, Brazil, Guatemala and Honduras.

Mexico

Last year, Mexico’s federal government required all of its 32 states to implement a U.S.-style “adversarial” system of criminal procedures, eliminating its longstanding but flawed “mixed inquisitorial” legal model, as of June 18. More than likely, the transition will be a gradual and difficult one. The nation made the effort amid the mounting ferocity and brutality the country’s organized crime groups and cartels impose upon almost every level of its society.

Mexico is seeing a “dramatic” increase in crime and violence in recent years, and both the rate and number of homicides are the highest in the Western Hemisphere, according to a report titled “Drug Violence in Mexico: Data and Analysis Through 2016,” released in March by the research institute Justice for Mexico at the University of San Diego.

Many of the killings are the result of clashes among rival drug trafficking gangs, related at least in part to the void created since the capture and recent extradition to the United States of the Sinaloa drug kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, according to the report. Guzman, who was arrested last year after escaping from a Mexican maximum-security prison in 2015, is in federal custody in New York and could face a life sentence on charges that include murder, racketeering, and drug trafficking.

During the administration of former President Felipe Calderon from 2006 to 2012, Mexico recorded more than 121,000 murders, or about 55 per day. While homicides dropped over the following two years, murder rates picked up by 20 percent in 2016 and grew in 24 of Mexico’s 32 states. The top three murder states were Colima (killings up 600 percent), Nayarit (up 500 percent) and Zacatecas (up 405 percent) where organized crime groups are vying for control over drug production and trafficking. Seven serving or former mayors were assassinated in Mexico in 2016, as were 11 journalists, Justice for Mexico reported.

“What is particularly concerning about Mexico’s sudden increases in homicides in recent years is that much or most of this elevated violence appears to be attributable to ‘organized crime’ groups, particularly those involved in drug trafficking,” the report’s authors stated.

About one fourth to 40 percent of homicides within Mexico “bear signs of organized crime-style violence, including the use of high-caliber automatic weapons, torture, dismemberment, and explicit messages involving organized crime groups,” they wrote.

Beyond the findings of the study, recent media reports suggest the level of violence by organized crime in Mexico is even worse. An analysis by the Mexican media site Animal Politico estimated that OC groups were responsible for six in 10 homicides in Mexico in 2015 and that Mob-connected murders swelled by 47 percent during the first nine months of 2016. In February, Mexico sent 500 military police to the southwestern state of Colima after a sharp rise in violence and killings attributed to a war between the Sinaloa and Jalisco-New Generation cartels.

Major drug cartels have long been considered the center of underground crime in Mexico.

Major drug cartels have long been considered the center of underground crime in Mexico. But how many of them are still in operation is currently in dispute. Some crime analysts believe the entire nature of organized crime in the country has changed, that the old “cartels” have fallen apart into smaller sub-regional criminal clans, with factions from some cartels uniting with those of others, largely because various cartel bosses have been either killed or imprisoned. Some of these new criminal bands are specializing in multiple offenses (in addition to the usual of trafficking of heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and cannabis) such as kidnapping, extortion, manufacturing chemical precursors to synthetic drugs and levying a fee, called a “piso,” to permit drugs to be smuggled through their territories.

The debate over cartel activity is raging even within the Mexican attorney general’s office. The list of cartels for years has included the Beltran Leyva Organization, Familia Michoacana, Gulf, Jalisco-New Generation, Juarez, Knights Templar, Sinaloa and Los Zetas. To Tomas Zeron, director of criminal investigations for the AG’s office, only two cartels are viable and operating in Mexico today, the Sinaloa and Jalisco-New Generation. But officials at SEIDO, the AG’s organized crime division, count seven cartels, some created from groups that have splintered off from the traditional criminal alliances such as the Beltran Leyva, Familia Michoacana, Sinaloa and Los Zetas.

Brazil

Brazil, with 200 million people, has the largest economy in Latin America at $1.7 trillion in 2015. It is also among the most violent countries in the world with about 27 murders per 100,000 people as of 2011. Many of those killed are black men lured to join drug gangs in impoverished urban areas. Brazilian military police are killed at one of the highest rates in the world while battling organized crime and street gangs.

The country’s criminal organizations are dominated by three “Comando” (drug trafficking) syndicates, the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), Comando Vermelho and Amigos dos Amigos. These groups are in on sales of cocaine, crack and other illegal drugs, as well as Brazil’s enormous firearms trafficking rackets and various illegal businesses. The PCC gang practically runs Brazil’s overcrowded prison system, as advanced by a simultaneous riot it organized in 82 prisons in 2006, which killed 38 military police officers, guards and civilians and triggered a series of unsolved extrajudicial murders by police.

But the bigger story in Brazil is about the criminal rackets run by its own government. In terms of political corruption among government officials and the privileged few around the world, what Brazil is currently going through takes the cake. It involves billions of dollars’ worth of cash from kickbacks spread like a dense fog over the country’s public administrative and legislative officials.

Brazil has been in the throes of a national political scandal known as “Operation Car Wash” for the past three years. The first domino fell in August, with the impeachment and removal from office of Brazil’s unpopular second-term President Dilma Rousseff. Rousseff’s forced exit followed allegations that she abrogated budgetary regulations by shuffling government funds from one public agency to another to cover up deficits, a practice she claimed was common among her predecessors.

Then, on April 12, “Operation Car Wash” came to a head. Brazil’s Supreme Court authorized an investigation into 108 of Brazil’s elected and political elites – including eight cabinet ministers, leaders of the two chambers of Congress, 24 senators, 39 congressional deputies, three state governors and even five former Brazilian presidents. The ruling followed testimony – given in exchange for plea bargains — by 77 former employees of Odebrecht Construction Group. The company is accused of being the center of a $2 billion graft scheme with other construction firms seeking favor among Brazilian politicians to win government contracts and weaken regulations. It is Brazil’s worst corruption scandal ever.

The debacle is an outgrowth of more than a decade of scandals befalling Rousseff’s reformist Workers’ Party since it gained power through election majorities in Brazil in 2003. Two years later, a scandal came to light named “Mensalao,” where the Workers’ Party-controlled government doled out public funds to members of Brazil’s Congress in exchange for votes on legislation. It took a while to jell but 25 office holders – some who were leaders of the Workers’ Party — and private businessmen were convicted of corruption charges in 2012 after a trial overseen by the Supreme Court.

Brazil has faced more than a decade of political scandals.

“Operation Car Wash,” broke in 2014. Prosecutors said that Brazilian construction companies overcharged the country’s nationally owned oil firm Petrobras for building projects, then oil company executives doled out funds to themselves and members of the Workers’ Party and other political parties with millions in cash and campaign contributions. The Workers’ Party allegedly used some of the money to fund its election drives. Prosecutors maintain that a major player in the scheme was former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, or “Lula,” of the Workers’ Party, who served from 2003 to 2011. Lula has denied involvement.

At first, Brazil’s sitting President Michel Temer, mentioned by some judges in evidence presented, was not among those under investigation, possibly since he has temporary immunity against crimes that occurred before his election as president. But those on the list include Temer’s chief of staff and eight of the president’s cabinet ministers. So are former Brazilian presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Jose Sarney, Fernando Collor de Mello, Rousseff and Lula da Silva.

Some one-time Odebrecht executives, in sworn testimony, have alleged that Temer himself took part in soliciting a $3.2 million bribe from them. Separately, according to a court transcript released on April 12, Marcio Faria, a former Odebrecht administrator who is seeking a plea bargain, testified that during a meeting in 2010, Temer requested the construction company give a 5 percent kickback of the value of a Petrobas contract to Temer’s Brazilian Democratic Movement Party. The kickback, Faria said, amounted to $40 million. Faria claimed that Temer’s party later shared about 20 percent of the funds from the alleged kickback with the Workers’ Party.

The developing scandal will have repercussions for Brazil’s 2018 presidential race, since most of the likely candidates, including Lula, are targets of the investigation, and Faria’s claims may cripple Temer politically.

Brazil also suffers financial harm to its economy, amounting to as high as $40 billion a year, in lost business and government tax revenue from organized criminals who import and sell counterfeit products, such as mobile phones and tobacco, on the black market.

Guatemala

One of seven small nations in Central America between Mexico and South America, Guatemala has long been known as among the most corrupt – and poorest — countries in the world, in an area it shares with Honduras and El Salvador known as the Northern Triangle. Last year, seizures of cocaine exceeded 10 tons, eclipsing the record set in 1999.

But lately organized criminal conspiracies have reached the highest levels of its elected government. Former President Otto Perez Molina and ex-Vice President Roxana Baldetti remain in jail after resigning in 2015 in an alleged $130 million bribery, customs and tax fraud conspiracy whereby bribes were solicited and paid so that private businesses could enjoy reduced taxes on products imported into Guatemala. More than 20 people were arrested, including Perez Molina’s ministers of customs and tax administration. As many as 60 government employees, private lawyers and import business people were allegedly tied to the scheme.

The outraged Guatemalan public refers to the customs and tax scandal as “La Linea,” the line. But prosecutors contend that “La Linea” was only part of a broader conspiracy of bribery and money laundering, one that led Guatemala’s two top leaders to acquire $4.7 million in expensive property and luxuries from public funds arranged by five members of Perez Molina’s cabinet who were all charged last year.

Insight Crime, a news website dedicated to organized crime in Latin America, declared that Perez Molina and Baldetti, after their election win in 2011, “set up what can only be called a Mafia state in which they employed various parts of the government to service corruption and criminal schemes.”

An investigation by the U.N.-supported International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), formed with the help of the United States to expose and prosecute political corruption and joined by the country’s Attorney General Thelma Aldana, offered up wiretaps that the prosecution claims incriminate both former leaders in spearheading the plot. An alleged member of the conspiracy testified that Perez Molina and Baldetti took about one-fifth of the proceeds of the bribes that amounted to more than $300,000 a week.

More damaging revelations for Perez Molina and Baldetti have emerged, as prosecutors accuse them of taking $38 million in kickbacks from 2009 to 2015 in exchange for support for about 70 public works contracts in the country. Baldetti, they said, traveled to Miami and spent about $40,000 on liposuction surgery and expensive clothing, while Perez Molina purchased a farm. Perez Molina’s allegedly corrupt cabinet ministers, after receiving parts of the booty, gifted their boss a boat, helicopter and beach house, while Baldetti collected a second home on an island off the coast of Honduras.

Further, prosecutors said the two obtained a $30 million bribe from a Spanish shipping company in exchange for granting it an exclusive contract to manage Guatemala’s largest shipping port, and then the pair attempted to launder the money.

Guatemalan Attorney General Thelma Aldana last summer publicly stated that she feared “hidden powers” in Guatemala were trying to inhibit her.

Last month, not only did the scandals widen, but Guatemala’s latest president Jimmy Morales appeared to have triggered another one, with international implications. U.S. officials announced they would seek to extradite Baldetti and Guatemala’s jailed former Interior Minister Hector Lopez Bonilla after a federal grand jury in Washington, D.C., indicted them and others on charges of conspiracy to traffic cocaine to the United States between 2010 and 2015.

That came on the heels of a statement by U.S. Senator Patrick Leahy, a Vermont Democrat, warning Morales to back off any bid to block the reappointment of Ivan Valasquez, who heads the CICIG. Leahy observed that Velasquez’s term expires in September. The senator also put Morales on notice not to impede the work of Attorney General Aldana, who last summer publicly stated that she feared “hidden powers” in Guatemala were trying to inhibit her.

The CICIG under Valasquez, and Aldana’s office, cooperated in investigating the intersections of organized crime with Guatemala’s politicians and wealthy businesspeople that led to the charges against Perez Molina, Baldetti and Lopez. Perez Molina and Baldetti have repeatedly denied all the charges against them. Lopez is also suspected of providing free government security services (while serving as Perez Molina’s interior minister) to accused drug lord Marllory Chacón Rossell, a k a “the Queen of the South,” who has been in U.S. custody after confessing in 2015 to being a top drug trafficker. Lopez disputes the allegations.

Leahy indicated that the United States could cut off hundreds of millions in funds approved by Congress to fight the corrupting power of organized crime in Guatemala and the rest of the Northern Triangle if its president interfered with the corruption probes. Morales won the presidency in the wake of the Perez Molina’s 2015 resignation.

Money laundering, embezzling public money, illegal drug rackets.

Aldana herself, due to her role in the corruption inquiries, may have been targeted for assassination by a top Guatemalan drug trafficker, Marlon Monroy Meono, a k a “The Ghost,” according to the country’s Interior Minister Francisco Rivas. Fortunately, Monroy, a former military officer, was arrested last year and extradited to the United States along with his wife, Cynthia Janeth Cardona. Both arrived in Miami to face drug trafficking charges in federal court. Last September, a Guatemala-based magazine reported that Monroy stated that the son of Guatemala’s current Vice President Jafeth Ernesto Cabrera Franco accepted $500,000 to consider allowing Monroy to name individuals to be appointed to high-level drug enforcement positions in Morales’ government. Morales’ office insisted that Monroy was lying based on his resentment over being arrested by the Morales administration.

Meanwhile, Emilenne Mazariegos, a former member of the Guatemalan Congress, was put in jail in March after she and 11 others were arrested on suspicion of money laundering and embezzling public money intended to pay for local government projects. The Huistas, an organized crime group in the illegal drug racket in Guatemala, is suspected of injecting funds into Mazariegos’ campaign to ensure her election to the Congress in 2011.

Honduras

As with Guatemala, Honduras is fighting corruption in the highest echelons of a troubled government that saw its president forced out in a military coup in 2009. The latest developments there come via accusations by Devis Rivera Maradiaga, the jailed former boss of the Cachiros drug trafficking consortium, during his federal court trial in New York in March. The Cachiros crime group, with an estimated $1 billion in assets, for years afflicted Honduras by using the country as a route to transport cocaine the group bought from Colombian drug lords for sale to traffickers in Mexico. But in 2015, two of its top men, Rivera and his brother Javier, fearing for their lives in Honduras, agreed to be arrested by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration and extradited to the United States to stand trial on drug trafficking charges.

Rivera testified that he directly paid multiple bribes of up to $300,000 to Honduran politician Porfirio Lobo Sosa while Porfirio Lobo sought the country’s presidency following the 2009 coup and after the candidate won the election and took office. Further, Rivera claimed then-President Porfirio Lobo sent his son, Fabio Lobo, to facilitate the trafficking of tons of cocaine across the country by the Cachiros by procuring a bribe to benefit former Honduran general Julian Pacheco Tinoco, who served as an official security adviser to Porfirio Lobo.

Former President Porfirio Lobo has strongly denied the ex-crime boss’ allegations, and the office of Pacheco Tinoco, who now heads Honduras’ Security Ministry, maintains that Riviera told made-up stories in the U.S. court as a bargaining chip for a better sentencing deal.

Rivera also testified that a member of the Honduran Congress solicited a bribe from him on behalf of current President Juan Orlando Hernandez’s brother so that Riviera would secure government road and maintenance service contacts to businesses owned by the Cachiros crime boss and his family that are fronts for the group’s drug racket.

The Cachiros made news again in late March when the Honduran media reported that the organized crime group took advantage of more than two dozen public rebuilding projects to repair damage wrought by tropical storm Agatha in 2010. They allegedly laundered about $6.4 million through family-owned businesses hired by the Honduran government to do the construction work.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org