New York indictments allege Georgian mafia activities in four U.S. states

Criminal suspects include syndicate boss and boxing contender

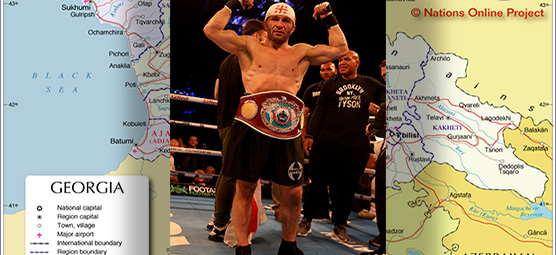

The country of Georgia, wedged between Russia and Turkey with the Black Sea forming its western border, gained its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Today, it is a member of the United Nations and has been making progress toward becoming a member of the European Union.

But while Georgia is constantly striving to distinguish itself politically and culturally from Russia, its leading organized crime groups, collectively known as the Georgian mafia, remain closely linked with organized crime in the former Soviet Union.

The illegal activities of the Georgian mafia were exposed last week when nearly three dozen members in four U.S. states were indicted in New York. Those indicted included a top World Boxing Association contender.

The case introduced a new term into the lexicon of American organized crime: “vor v zakonei,” which in Russian is translated as “thief-in-law,” or simply “vor,” another word for “boss.” Enjoying powers similar to those of traditional Italian Mafia bosses, a Russian “vor” is a respected leader of criminals from the former Soviet Union who receives tribute payments and protection from followers and mediates disputes among gangsters.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Southern District of New York on June 7 announced the grand jury had charged 33 members of the Georgian underworld operating in New York, Florida, Pennsylvania and Nevada with racketeering, narcotics trafficking, illegal gambling, fraud, robbery and murder for hire.

“The indictments include charges against the alleged head of this national criminal enterprise, one of the first federal racketeering charges ever brought against a Russian ‘vor,’” Acting U.S. Attorney Joon. H. Kim said. “The dizzying array of criminal schemes committed by this organized crime syndicate allegedly include a murder-for-hire conspiracy, a plot to rob victims by seducing and drugging them with chloroform, the theft of cargo shipments containing over 10,000 pounds of chocolate, and a fraud on casino slot machines using electronic hacking  devices.”

devices.”

U.S. prosecutors allege that what they described as the “Shulaya Enterprise” used an unidentified female member “to seduce men, incapacitate them with gas and then rob them.”

Considered the most powerful Russian mafia group, the Georgians are divided into two clans, associated with the two largest cities in Georgia. The Shulaya Enterprise, of the Kutaisi clan, is led by Razhden Shulaya, a “vor” in St. Petersburg, Russia. He was arrested June 7 in Las Vegas. He has a residence in New Jersey. Most of his co-conspirators live in Brooklyn.

Another defendant named by federal prosecutors is Avtandil “The Kickboxer” Khurtsidze, a 33-year-old professional prize fighter from Georgia and residing in Brooklyn who had been scheduled

to oppose Billy Joe Saunders of the United Kingdom for the WBO middleweight championship in July. That fight has been canceled.

Khurtsidze was arrested, as were most of the other defendants, on suspicion of violating the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. He was further charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

Another professional fighter, Levan Makashvili, who fought for Mixed Martial Arts and the Ultimate Fighting Championship, was charged with RICO and wire fraud conspiracy violations in the indictment.

While the Italian Mafia still controls most organized crime in New York City, Russian mobs dominate Brighton Beach, the historically Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn that has become known as “Little Odessa” (named after the largest city in Ukraine) for its influx of Russian nationals since the fall of the Soviet Union.

The Shulaya Enterprise allegedly extorted indebted gamblers and local business owners and operated an illegal poker game and after-hours club, where police were allegedly paid off to overlook the sale of narcotics.

Beyond Brighton Beach, prosecutors claim this criminal operation engaged in large-scale interstate trade in stolen goods, including 10,000 pounds of chocolate, stole personal financial data, created counterfeit credit cards and defrauded casinos by cheating slot machines.

In a separate indictment, the U.S. government has charged two members of Shulaya’s enterprise, Bakai Marat-Uulu and Nikoloz Jikia, with conspiring to murder the purported associate of an FBI informant and steal $1.5 million in contraband cigarettes in Manhattan and Brooklyn. In December 2015, Marat-Uulu was arrested near Chicago for “skimming” ATM machines using an electronic device that recorded victims’ credit card numbers.

Russian mafias have a reputation for creative uses of technology, which federal prosecutors allege some of the defendants put to use in this case to fraudulently win money from legal slot machines in Atlantic City and Philadelphia casinos by removing the element of chance.

One such machine was the “Pelican Pete” model, made by Aristocrat Gaming in Australia, a slot device named in the federal indictment. The machine has four rows of five digital “reels” each and multiple buttons. Players choose poker card colors and suits prior to games. If the player guesses the right color or suit, he receives a higher payout.

Catherine Sachs, a Massachusetts-based computer programming expert who holds master’s degrees in electrical and computer engineering and material science, said that video slot machine games such as Pelican Pete run gambling software that relies on pseudo-random number generators to maintain a fixed, mathematical edge for the house. The computers in these gaming machines have internal clocks that supply a “seed,” or “number plugged into an equation,” Sachs said. The result of the equation is used to generate another number, and another, until the number meets a rule, defined in the program, that tells the computer to generate a “pseudo-random” number that makes the machine’s moving virtual reels stop to show the game’s outcome.

“It is a common practice to use a computer’s internal clock to select the seed required by many pseudo-random number-generating algorithms,” Sachs said.

Organized cheaters may use a video recording taken of a working machine to help them predict the internal clock and the number assigned to stops on the reels. The data are put in the form of an Apple iPhone app, which generates a vibration a quarter of a second before the criminal player should press a button in order to win at a rate far exceeding the game’s original design.

In 2014, casinos in St. Louis, Missouri, were defrauded by St. Petersburg-based Russian mafia scammers who targeted the same machines as the Shulaya Enterprise. Murat Bliev of St. Petersburg, who is not named in this indictment, was arrested in 2015 along with three co-conspirators for allegedly defrauding casinos. An alleged co-conspirator, who remains unnamed and has not been sentenced, is reportedly assisting the FBI with investigations into slot cheating.

Shulaya, if convicted of the charges in the indictment, faces up to 65 years in prison. Marat-Uulu, named in two of the four federal cases revealed last week, including the murder-for-hire conspiracy, could be sentenced to life in prison.

Prosecutors stated that Marat-Uulu, who is also charged with two others with conspiring to sell cocaine and heroin, is heard on a recording made by a confidential FBI informant allegedly conspiring with co-defendant Jikia to murder a victim, cover the body in lime and bury it so that due to faster decomposition, “in a year, there won’t be a hair.”

Justin Cascio writes about health, identity, the family and organized crime. His articles on the Mafia have also appeared in The Informer and Mafia Genealogy.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org