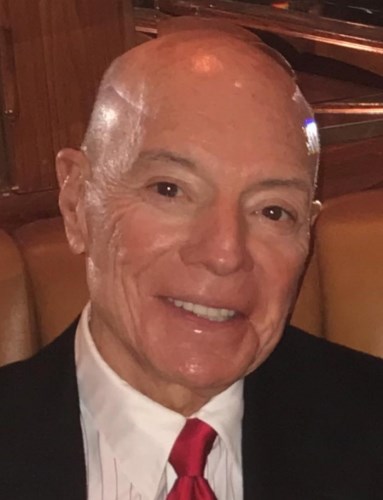

Allen Glick, 1970s owner of Las Vegas casinos skimmed by Mob, has died

Glick escaped prosecution by becoming government witness

Allen R. Glick, a decorated Vietnam War veteran and California developer who insisted he knew nothing about skimming by Midwestern mobsters at four Las Vegas casinos he owned in the 1970s, died August 2. He was 79.

Glick passed away in the seaside neighborhood of La Jolla in San Diego, his home for many years, following an extended battle with cancer, his family announced.

Glick was a central character in an infamous organized crime scandal that rocked the Las Vegas casino industry in the 1970s and was later dramatized in the 1995 movie Casino. Through his company Argent Corporation, Glick owned four casinos – the Stardust, Fremont, Hacienda and Marina – second only in number to the Nevada hotels owned by billionaire Howard Hughes at the time.

The Nevada Gaming Control Board later determined that employees of Argent’s casinos quietly skimmed about $7 million from 1974 to 1976 from slot machines on behalf of Milwaukee, Chicago, Kansas City and Cleveland crime families with hidden interests in the properties.

The saga ended in 1986 with the convictions and federal prison terms for more than a dozen top U.S. mobsters, including Milwaukee boss Frank Balistrieri (who pleaded guilty), Chicago Outfit leaders Joseph Aiuppa and Jackie Cerone, Carl DeLuna of Kansas City and Milton Rockman of Cleveland.

Glick swore he was not aware of the skimming, and indeed federal prosecutors never charged him criminally in return for his cooperation as a witness before two federal grand juries hearing evidence against the Mob-connected defendants.

The government defended Glick in court as a frightened tool of the underworld secretly responsible for loans from the corrupt Teamster pension fund used to buy the casinos.

However, the FBI would allege Glick hired a private attorney in Washington, D.C., to gather information on federal agents and the grand jury investigation into Argent and Glick to insulate him and others from the probe and possibly suborn perjury. Nevada gaming authorities revoked Glick’s casino license in 1979.

For years before everything went south for him in the late ’70s, Glick earned glowing reviews in background checks requested by prospective partners and the Gaming Control Board, based on his military service and clean business history.

A native of Pittsburgh, Glick was a graduate of Ohio State University and the Case-Western Reserve School of Law, then passed the bar in California and Pennsylvania. In 1967, he joined the U.S. Army, serving in Vietnam as a military police lieutenant and then as a captain in Special Operations. The Army awarded him the Bronze Star and three combat air medals for his part in search-and-rescue missions.

Upon leaving the Army in 1969, Glick took a job in San Diego with a suburban home-building firm, the American Housing Guild, and two years later joined the real estate company Saratoga Development Corporation. In 1972, the ambitious Glick used a $2.3 million loan from Saratoga to acquire a major and later controlling share in the Hacienda hotel-casino in Las Vegas, and obtained a Nevada casino license.

The next year, Glick met with Alvin Baron – asset manager of the Teamsters Union’s pension fund and a close associate of former Teamsters president James Hoffa – and Ed Buccieri, a reputed money courier for mobster Meyer Lansky. A plan to buy the King’s Castle casino at Lake Tahoe with Baron and Buccieri fell through, but Glick was now in close contact with pension fund chiefs.

In 1974, Glick set his sights on the Stardust hotel-casino on the Las Vegas Strip. Top leaders of the Milwaukee and Kansas City families took a meeting about Glick. As it happened, Glick knew Joseph Balistrieri, son of Milwaukee Mob boss Frank Balistrieri, from college. Glick then convened privately with Frank Balistrieri that April.

Out of those meetings came a sweetheart deal: Glick would buy the Stardust and Fremont casinos by purchasing control of Recrion Corporation (formerly Parvin-Dohrmann, owned by Delbert Coleman). Then, that June, he agreed to allow Balistrieri’s sons, Joseph and John Joseph, the option to buy Glick’s Argent Corporation for a mere $25,000. Glick thereby curried favor with the Mob boss, who used his clout to gain a big loan from the pension fund.

Glick met with Kansas City Mafia leader Nick Civella (who died in 1983). Frank Balistrieri sought the help of Kansas City, Chicago and Cleveland bosses to get a Teamsters pension fund loan.

Finally, Glick, at age 32, received a $62.75 million loan from the pension fund. Another investor, wealthy California matron Tamara Rand, would loan him $2 million (and later, on orders from Mob leaders, was killed gangland style).

As of the fall of 1974, Glick owned the Stardust, Fremont and Hacienda. In October, he announced that Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal would serve as his executive consultant for the three casinos. Later, state gaming investigators learned that the Mob’s skimming operation began that November.

In May, 1975, Glick opened a fourth casino, the Marina, owning 65 percent of the casino portion.

Rosenthal and Glick would revolutionize sports betting in Las Vegas by adding a large, elaborate sportsbook at the Stardust. Glick and Rosenthal also brought the up-and-coming Siegfried & Roy magic act to the hotel.

A crooked oddsmaker with ties to Chicago Outfit leader Joseph Aiuppa, Rosenthal turned out to be the overseer for the Mob’s interests and embezzlement of slot machine coins in all four casinos. U.S. investigators also alleged Outfit made man Tony Spilotro had a hand in the operation.

While the Mob’s associates stole from the casinos, Glick, ensconced in his executive office at the Stardust, claimed to be unaware of the skimming that lasted for two years.

State officials discovered and ended the scheme in May 1976. The U.S. Justice Department launched a criminal probe into Glick, who escaped prosecution with his testimony for the feds. In June 1978, the FBI sent 50 agents to Las Vegas, with 83 search warrants, in a series of raids centered on Argent, based on wiretaps and other evidence.

By 1978, Glick, now owing the pension fund $94 million, had fired Rosenthal. Civella, he told federal investigators, before his death threatened to kill Glick’s sons if he did not sell Argent. Glick sold his Las Vegas casinos in December 1979 and returned to San Diego, still worried about potential Mob retaliation against him and his family.

The story of Glick and Argent is central to the book Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas, by author and screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi. With director Martin Scorsese, Pileggi co-wrote the screenplay for the 1995 movie Casino. The Glick character in the movie, named Phillip Green, was played by Kevin Pollak.

Glick saw Las Vegas casinos as a business opportunity, but he was naive about the strings attached to the Teamsters loans he received to expand his operations in Southern Nevada, Pileggi said. “Allen Glick walked into this nightmare without knowing it was a nightmare,” Pileggi said.

When Glick realized how much trouble he was in, he didn’t know where to turn, Pileggi said. Believing that more than a few federal and state authorities in Nevada were in bed with underworld operatives, Glick feared that if he reached out to the wrong officials, those people would let the Mob know, Pileggi said. That could have been the end to Glick’s life.

“Glick was in a dangerous spot,” Pileggi said, like a “frog in the pot that’s slowly boiling.”

Ultimately, Glick found a federal agent he could trust and became a witness, Pileggi said. Glick’s later trial testimony was key to ending the Mob’s lucrative skimming operation in Las Vegas.

When writing the book, Pileggi met with Glick, who came across to the author as smart and cautious. Glick had security around during this time. Reflecting on Glick’s years in Las Vegas, Pileggi said he doesn’t think the former casino owner knowingly served as a front for the Mob or was involved in the skimming operations. If he had been, the FBI would have come after him, too, Pileggi said.

Larry Henry, who writes the Mob in Pop Culture blog, contributed to this report.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org