As the 75th anniversary of the Flamingo Hotel approaches, The Mob Museum is set to unveil a new exhibit

Insights and rare artifacts will be focus of exhibit on Bugsy Siegel and the origins of the iconic Strip resort

Ask many Las Vegas newcomers and visitors to identify the city’s origins, and they will say a mobster named Bugsy Siegel invented the town. Although this is a myth nurtured and perpetuated by fact-challenged writers and creative filmmakers, it is nonetheless fair to say that Siegel had a significant impact on Las Vegas — both intentionally and unintentionally.

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel’s seven-year involvement with the city, from 1941 to 1947, culminated in the Flamingo Hotel, a $6 million casino resort that set a new standard of quality for Las Vegas. The Flamingo’s sleek design, modern décor and luxury amenities represented a dramatic turn for a town that had previously embraced a dust-covered Old West theme. Siegel’s vision expanded upon the more modest plans of Billy Wilkerson, who conceived and started the Flamingo’s construction.

But Siegel’s enduring impact on Las Vegas has been felt even more because of something over which he had no control. On June 20, 1947, six months after the Flamingo’s opening, Siegel was murdered in Beverly Hills, California. Police investigations uncovered multiple motives, but resulted in no arrests, and Siegel’s killer is still a mystery almost 75 years later. The murder of Siegel, which generated front-page headlines across the country, ultimately contributed to the allure of Las Vegas. Many visitors were drawn to the city on the prospect — however realistic — that the guy sitting next to them at the poker table or the bar might be in the Mob. This sense that Las Vegas offered opportunities to rub shoulders with the underworld — without any real complications — boosted the city’s growth more than any single casino ever could.

And so, beyond the details of his comings and goings in Las Vegas during the 1940s, Siegel has become a central figure in the city’s history. He was the first larger-than-life organized crime personality in Las Vegas. In his local dealings, he generated mostly positive feelings. His Las Vegas lawyer, Lou Wiener, recalled in his oral history that Siegel “was a visionary, and he was a great guy.” Wiener said that when Siegel died, “I felt I lost a good friend. … I was a great admirer of his, not for what he did if he did do it, but for what he did here.”

Although never convicted of murder, Siegel was widely regarded as a brutal enforcer and hit man, from his adolescence in New York through his racket-building years in Los Angeles. He narrowly escaped a murder conviction in Los Angeles when a key witness, Abe Reles, fell out of – or was tossed out of – a hotel window. Wiener and others certainly saw a different side of this hoodlum, who had Hollywood good looks and a temper that earned him a nickname he hated. The Las Vegas version of Ben Siegel perhaps was the man he wanted to become – a legitimate businessman.

The true origins of the Flamingo — and Siegel’s role in it — remain muddled for those who have relied on Hollywood to tell the story. Reflecting its ongoing commitment to accurately interpreting the history of organized crime and law enforcement, The Mob Museum will unveil a new exhibit, The Fabulous Flamingo, on Friday, August 13. This exhibit and its artifacts aim to pierce the myths and set the record straight.

Before the Flamingo

First, Las Vegas was a well-established community long before Siegel arrived. Founded as a railroad town in 1905, it expanded dramatically in the early 1930s with the construction of nearby Hoover Dam and the statewide legalization of gambling. Hoover Dam, completed in 1935, became a popular tourist attraction.

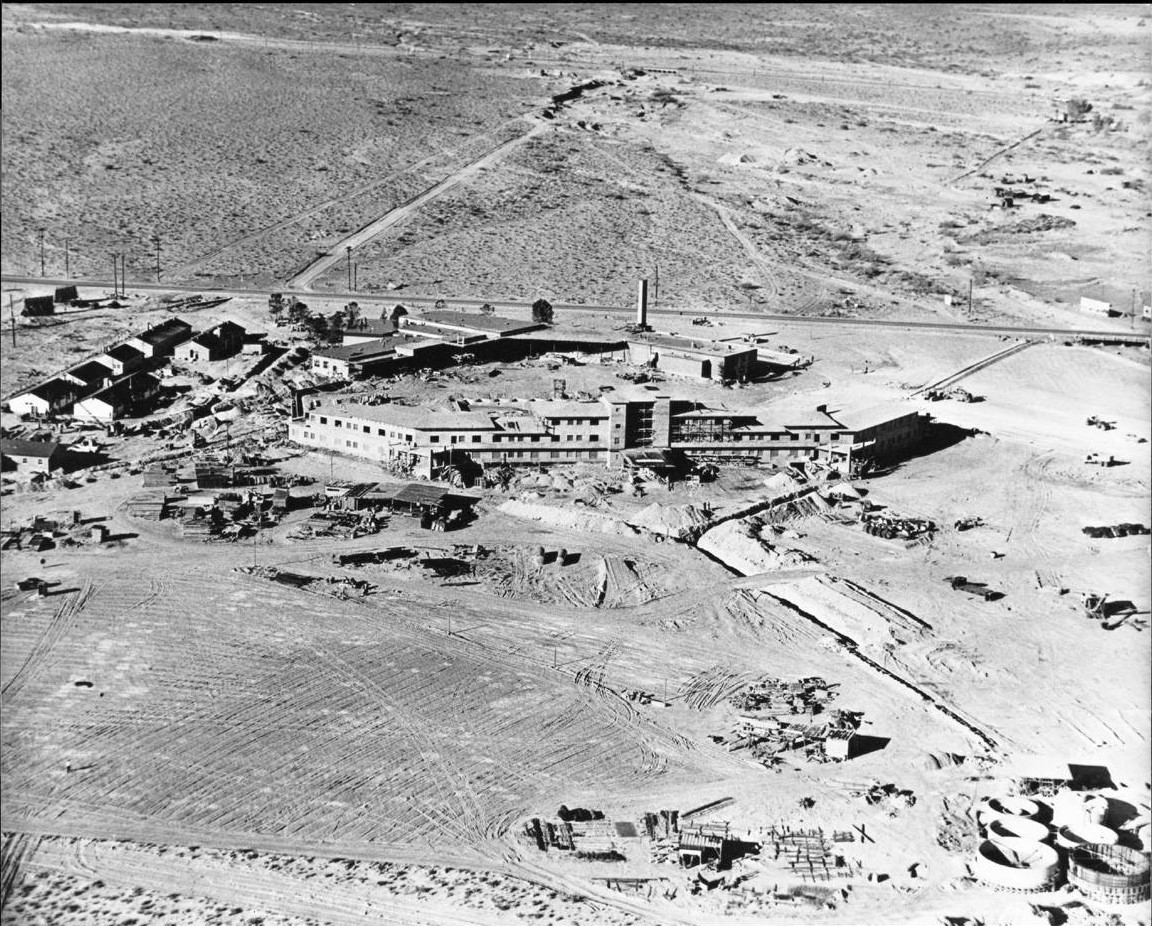

Las Vegas took another big leap forward in the early 1940s with two war-related projects: an Army air base and a magnesium processing plant. Both projects brought thousands of men and women to the Las Vegas Valley. The population explosion spurred the development of two casino resorts on Highway 91, south of Las Vegas. The El Rancho Vegas opened in 1941, and the Hotel Last Frontier debuted in 1942. These were the first two resorts on what eventually would become known as the Las Vegas Strip.

Meanwhile, Fremont Street in downtown Las Vegas continued to expand as well. The El Cortez opened in 1941, the Pioneer Club in 1942 and the Golden Nugget in 1946. The notion that Siegel “invented” Las Vegas is pure fantasy.

Siegel himself certainly knew this. Before he became involved with the Flamingo in 1946, he had invested in other Las Vegas casinos, and he was very involved with the race wire here. The race wire was a service that transmitted horse race information and results around the country. The timely availability of this information allowed bookies to take off-track bets. The Mob seized control of the race wire business, with Siegel in control of the Southwest, including Las Vegas.

Las Vegas was particularly valuable because Nevada was the only state that permitted off-track betting. As a result, Siegel, through his partner, Moe Sedway, operated the race wire in a number of Fremont Street casinos. By the mid-1940s, Siegel reportedly was receiving $25,000 per month in race wire payments from race books in Las Vegas.

Records show that in August 1941, Siegel invested $18,000 in the Northern Hotel on Fremont Street. He then heavily invested in the Frontier Club, also on Fremont Street. In 1943, Siegel tried to buy the El Rancho Vegas on Highway 91, but his offer was refused. Interestingly, Siegel’s underworld reputation kept him from acquiring the El Rancho Vegas. Its founder and owner, Thomas Hull, seeking to quell rumors, told the Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal, “The people of Las Vegas have been too good to me for me to repay them in that way. Mr. Siegel has contacted me several times with an offer to purchase, but I have told him I was not interested, and that goes for all time.”

Two years later, Siegel joined a group of fellow mobsters in the purchase of the El Cortez. They sold it a year later, presumably pouring their profits from the sale into the Flamingo’s construction.

Wilkerson’s vision, Siegel’s legacy

Not only did Siegel not invent Las Vegas, he did not even invent the Flamingo. That credit goes to Billy Wilkerson, publisher of the Hollywood Reporter newspaper and owner of a number of stylish Los Angeles restaurants and nightclubs.

Wilkerson bought the land on which the Flamingo would be built, and he started construction in late 1945. But Wilkerson, a compulsive gambler, soon ran short of funds. He had lost hundreds of thousands of dollars at casinos on Highway 91 and on Fremont Street. He turned to the Mob for financial help. Siegel, the Mob’s point man in Las Vegas, worked side by side with Wilkerson for a few months, but disagreements ensued, and Siegel eventually forced Wilkerson out and seized full control of the project.

Siegel opened the Flamingo on December 26, 1946. The crowds came, at first, and the critics fawned, but the Flamingo had a fundamental problem: Its hotel rooms were still not finished. Further, the casino experienced a strange run of bad luck, as gamblers won more than they lost in the first few weeks after opening. “Bad luck largely explained the losses,” according to Siegel biographer Larry Gragg. “For several nights many gamblers captured big wins.” But, Gragg notes, some of the losses could be attributed to incompetent or corrupt dealers.

Siegel’s rush to start generating revenue for his impatient investors forced him to shut down the Flamingo on February 6, 1947, until the rooms were finished. The resort reopened on March 1, with 100 guest rooms available, and performed better. Siegel’s apparent confidence in improving returns prompted him to schedule a vacation with his two daughters in late June. He traveled to Los Angeles to meet their train from New York.

But on June 20, 1947, while sitting on a couch in girlfriend Virginia Hill’s Beverly Hills house, Siegel was shot to death, leaving a murder mystery that lingers to this day. The Flamingo thrived after Siegel’s demise, setting a new standard for Las Vegas casino resorts with its sleek, modern façade and lavish appointments. Today, the Flamingo remains one of the largest and most recognized resorts on the Strip, though none of the original buildings still stands.

The key artifacts

The Mob Museum’s exhibit is highlighted by several rare artifacts that help to establish the true story of the Flamingo’s origins.

Down payment check

The exhibit includes the original check Billy Wilkerson wrote as a down payment to purchase the property where the Flamingo would be built. The check, written for $9,500 and dated March 5, 1945, went to a local businesswoman named Margaret Folsom. In total, Wilkerson paid $84,000 for the 33-acre parcel, which would be $1.2 million in 2021 dollars.

Casino checks

Also displayed will be five original checks that Wilkerson wrote to five different Las Vegas casinos to pay gambling debts he incurred during the Flamingo’s development. Wilkerson’s compulsive gambling problem, which lost him hundreds of thousands of dollars at Las Vegas casinos, forced him to seek out underworld investors to finance his casino project.

Grand opening invitation

The exhibit will include an original invitation to the Flamingo’s three-day grand opening. This invitation is for the third opening night, December 28, which focused on attracting Hollywood’s elite to see and enjoy the new resort.

Siegel-signed legal document

The premier artifact in the exhibit is an original legal document, signed by Siegel, removing Wilkerson in all respects from the Flamingo operation. In this agreement, Siegel promises to pay Wilkerson $600,000 for his interest in the casino resort. Wilkerson received half the money before Siegel was killed; he never received the other half.

Ralph De Luca, a prominent collector and member of The Mob Museum’s Advisory Council, aided the Museum in acquiring the legal document at auction and provided financial support for its purchase.

These signature artifacts are supplemented by other unique and hard-to-find objects, including a pair of sunglasses owned by Siegel; a pistol owned by Siegel partner Moe Sedway; a ceramic flamingo given to grand opening guests; and a colorful Flamingo slot machine from the casino’s early years.

In addition, the exhibit features a touchscreen so that guests can dig deeper into the Flamingo story. The touchscreen offers iconic images and compelling stories from the 75 years the Flamingo has graced the Las Vegas Strip.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org