The story of Al Capone and Eliot Ness is headed for Showtime

Upcoming series will look at ‘Untouchable’ agent’s efforts to topple ‘Scarface’

The shooting death of seven gangsters in Chicago on February 14, 1929, was “the most cold-blooded massacre in the history of the city’s underworld,” the New York Times reported the next day.

This gruesome incident, which took place in a garage at 2122 N. Clark Street, near Lincoln Park, became known as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. The dead were members and associates of George “Bugs” Moran’s North Side Gang, rivals of Al “Scarface” Capone during the bloody bootlegging years in 1920s Chicago.

The massacre shocked the nation and brought even more attention to rampant crime in Chicago during that period. To this day, the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre symbolizes this out-of-control era.

Ever since that dark morning, dozens of books and movies about the Chicago underworld during Prohibition have been produced. Even Nobel Prize winner and Chicago-area native Ernest Hemingway, born in 1899, the same year as Capone, referenced that outlaw environment in some of his ground-breaking fiction.

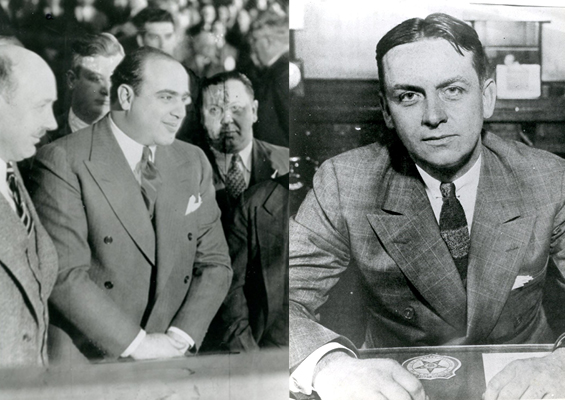

An upcoming television series on the Showtime network is expected to attract even more attention to Capone – and to Eliot Ness, a federal Prohibition agent who was tasked with going after Capone. Ness and his team became known as the Untouchables because of their resistance to corruption.

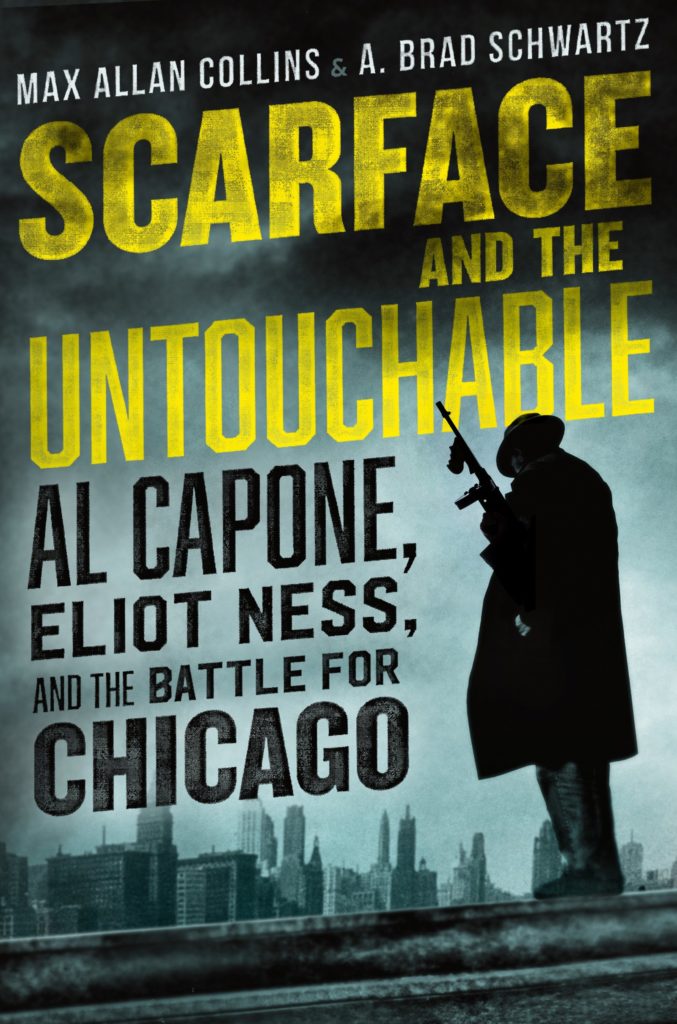

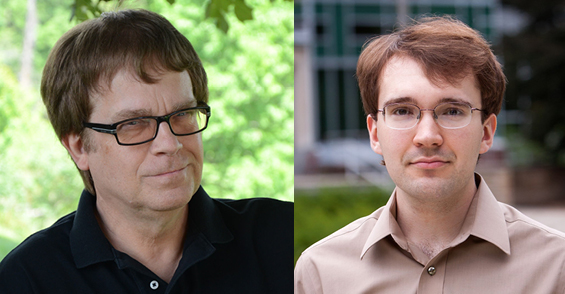

The Showtime production, now in its early stages, is based on the 2018 book Scarface and the Untouchable: Al Capone, Eliot Ness, and the Battle for Chicago by Max Allan Collins and A. Brad Schwartz. Collins and Schwartz spoke at The Mob Museum after the book’s release.

“The show will delve into Prohibition-era politics, industrialization, mass media, the immigrant experience, law enforcement and the birth of organized crime,” according to Deadline. “It will show how Al Capone corporatized crime on a level never before imagined, and how Eliot Ness, one of the most revolutionary cops in American history, fought an uphill battle to reform law enforcement, a battle that continues to this day.”

A date has not been set for when the series will air.

Capone’s vault

Capone is one of the main criminal figures from Prohibition whose name is still widely recognized. His nickname, Scarface, is well-known, the result of an incident in a New York bar, when Capone insulted a female customer. The woman’s brother, Frank Galluccio, pulled a knife and slashed Capone three times on the left side of his face. The longest scar extended to four inches.

Schwartz, co-author of Scarface and the Untouchable, said the public’s fascination with Capone “seems to come in waves every three or four decades.”

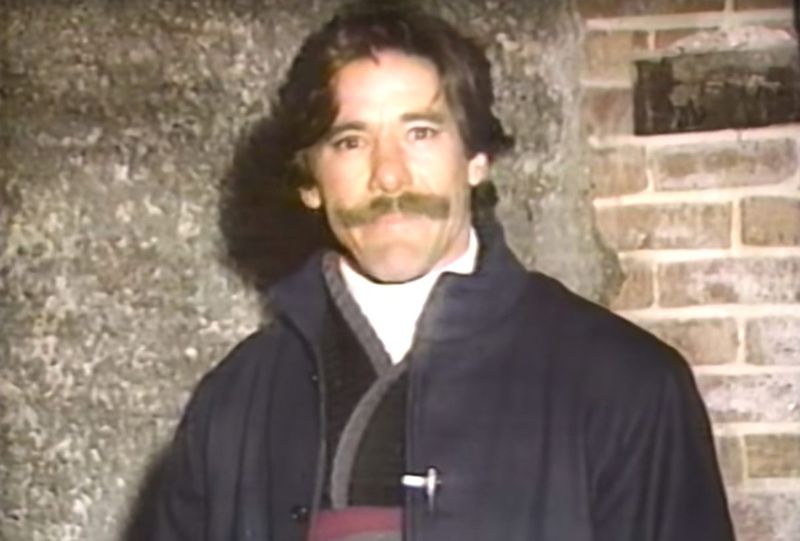

One of these waves occurred in April 1986 with reporter Geraldo Rivera’s live, two-hour televised broadcast from a basement vault in Chicago’s Lexington Hotel, a one-time Capone headquarters. Near the end of the broadcast, Rivera revealed there was nothing Capone-related in the vault and nothing of value, just an empty “60-year-old bottle” that he tossed aside.

“I’m disappointed about that, as I’m sure you are,” Rivera told viewers.

Rivera’s show about Capone’s vault continues to crop up as an example of how hype and overblown expectations can lead to ridicule. The veteran reporter “respectfully” declined requests to discuss the broadcast for this report, said Fox News spokesman Connor Smith.

According to Schwartz, however, Rivera’s show has gotten a bad rap.

“The documentary portions are actually quite good,” Schwartz said, “especially some of the interviews and footage inside the old Lexington Hotel.”

Capone historian Mario Gomes said that while Rivera’s broadcast might have looked like a flop, “in reality it brought millions of viewers to watching the event.” Gomes is founder of myalcaponemuseum.com.

“The documentary shown before the vault opening was one of the reasons I got interested in this subject,” Gomes said. “It was riveting and well made, despite the empty vault. This show brought many fans and collectors to seek out the Lexington Hotel to salvage anything from Al Capone’s suite, such as his famous Nile green bathroom tiles.”

‘The gangster mythos’

The public’s desire to know more about Capone has gone on for a long time and shows no sign of ending. During the height of his power, his “immense fame caught the eye of Hollywood,” Schwartz said.

Hollywood’s interest in Capone led to classic movies such as Little Caesar (1931) and Scarface (1932), which established the gangster genre, Schwartz said.

Three decades later, Capone and Ness were fading from popular memory, Schwartz said, “until several films and TV shows set in Prohibition-era Chicago all came out in 1959: Al Capone, The Untouchables, and Some Like It Hot.”

“And nearly 30 years after that, Geraldo opened Al Capone’s vault while the director (Brian De Palma), who remade Scarface, brought The Untouchables to the big screen,” Schwartz added. “I’d say we’re overdue for another revival. Showtime is working to make it happen.”

The author said Americans who “fell in love with Capone in the Roaring Twenties, when he offered himself up as a symbol of success, came to hate him in the 1930s, once the Great Depression made his lavish lifestyle seem obscene.”

“And because he made himself so visible in the mass media of his day, his personal style — his fedoras, suits, cigars and Tommy guns — became our cultural image of what it means to be a gangster,” Schwartz said. “He’s the truth behind the gangster mythos – and because that genre will always be with us, he’ll always be with us, too.”

Unsolved shooting deaths

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre stands out as one of the most disturbing deadly episodes in U.S. criminal history.

At about 10:30 on that cold February morning, some in the garage had been drinking coffee at an electric stove and eating crackers when intruders lined all seven Moran gang members up against a white-washed brick wall and gunned them down. Two of the four gunmen were disguised in police uniforms, “their stars gleaming against the blue of their cloth,” the New York Times reported. Two men had Thompson submachine guns, and at least one had a shotgun. Police found more than 70 machine gun shells on the blood-stained floor.

The only survivor was a German shepherd named Highball. The dog belonged to John May, an overall-clad mechanic and suspected safe-blower killed in the massacre.

At the time of the shooting, Capone was in Miami, where he had a home, but he is believed to have ordered the attack, thereby strengthening his grip on many illegal enterprises in Chicago. That would not last long. In 1931, he was sentenced to 11 years in federal prison for tax evasion. Suffering physically and mentally from syphilis, Capone died in Florida in 1947 at age 48. Eight years before his death, doctors said he had the cognitive processes of a 12-year-old. (Family members dispute this depiction of Capone’s mental state in his final years.)

No one was ever held accountable for the massacre. After a private meeting with one suspect, Fred “Killer” Burke of St. Louis’ notorious Egan’s Rats, a Chicago prosecutor declined to file charges, according to historian and former Las Vegas casino executive Bill Friedman. The Chicago prosecutor instead deferred to a district attorney in Michigan, where Burke was wanted on suspicion of killing a policeman. Burke was convicted in that death and sentenced to a life term. He died of a heart attack at age 54 in a prison in Marquette, Michigan, near Lake Superior.

The site of the garage in Chicago now is an empty lot. A large portion of the bullet-pocked brick wall has been preserved and is on display at The Mob Museum.

Ness’s second chapter

Schwartz and Collins have written another book about that era, Eliot Ness and the Mad Butcher, which came out this summer in a paperback edition. The book picks up the Ness story in Cleveland, where he squared off against the Mob after Prohibition. Ness also was there to reform the police department and hunt down a serial killer, “long before most Americans knew such murders existed,” Schwartz said.

“That period challenged him even more than the Capone case, and his efforts to transform American policing are worth remembering as we try to reimagine public safety today,” the author said.

For his next project, Schwartz is taking a break from the gangster era to write about the early days of broadcast news. But the underworld, with its deep well of story material that writers and readers find irresistible, might draw him back in.

“I hope to return someday,” he said.

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org