When the Mob owned a minor-league hockey team

Netflix documentary series examines rise and fall of Mob-connected trash magnate’s brawling Connecticut squad

Standing up to a reputed Mob associate was a part of Richard Brosal’s job 15 years ago.

As commissioner of the United Hockey League, Brosal knew he could not back down in confrontations with Danbury Trashers owner James Galante. The team nickname derived from Galante’s trash-hauling company.

“Bullies are bullies until you stand up to them,” Brosal said recently. “If you allow somebody to strip you of your dignity, then shame on you.”

The Trashers were a rowdy minor-league team in Western Connecticut, playing in the Danbury Ice Arena about an hour and a half northeast of Manhattan.

Galante had handed the team over to his teenage son, a 17-year-old high-schooler named A.J. Together, the father and son encouraged their players to stir up trouble during games. “I wanted tough guys on the team,” James Galante said. He even once fought a referee.

The Trashers’ short but colorful existence, lasting from 2004-2006, is the subject of a Netflix documentary, Untold: Crime & Penalties. Galante was accused of defrauding the United Hockey League, in part by paying players extra under the table. He was imprisoned on federal racketeering and tax fraud convictions. He served six years, beginning in 2008. The league no longer exists.

In the documentary, Brosal discusses his confrontations with the Galantes, who, in the commissioner’s view, were embarrassing the league by encouraging on-ice muggings. Brosal’s mission was to “protect our image and our affiliation with the NHL,” he said.

Among other punitive actions, Brosal suspended the Trashers’ equipment manager, tough-talking Tommy “T-Bone” Pomposello. The equipment manager’s dirty tricks included turning off the hot water in the opponents’ locker room.

“He was a bigger thorn in my side than anybody else,” Brosal recently said from his office in Las Vegas.

The former commissioner now is CEO of Jet Luxury Resorts, a condominium management company. He works out of an office west of downtown Las Vegas near a practice rink where the National Hockey League’s Vegas Golden Knights prepare for games.

Though Brosal is friends with Golden Knights executives and takes in games at T-Mobile Arena on the Strip, the 62-year-old Southern California native has been a Los Angeles Kings fan for years. Brosal even attended a 1991 NHL preseason game in Las Vegas between the Wayne Gretzky-led Kings and New York Rangers. The game was held outdoors at Caesars Palace. Gretzky scored a goal in the Kings’ 5-2 victory.

Trash czar

Years ago, James Galante controlled an East Coast trash-hauling empire that federal authorities said was linked to the Genovese crime family and acting boss Matthew “Matty the Horse” Ianniello. Galante’s trash business at one time had 400 employees working in parts of New York and Connecticut.

James Gandolfini, who starred as fictional mobster Tony Soprano in the HBO series The Sopranos, once autographed a photo of himself and other cast members for Galante, referring to the trash czar as “the real Tony Soprano.” In the television series, Tony Soprano’s son, like Galante’s, is named A.J.

Since his release from prison, Galante, 68, has been involved with a company that delivers heating oil and propane, according to former FBI agent Ed Adams. Galante is prohibited from re-entering the trash-hauling business. His son, A.J., is owner of Champs Boxing Club in Danbury.

Adams said James Galante is a “regular guy” who enjoys spending time with his family. “Jimmy is a businessman,” Adams said.

Galante did not respond to questions submitted to him in writing through his attorney, Hugh Keefe. A.J. Galante did not reply to telephone voice messages left at the boxing club.

‘Three-ring circus’

In his youth, A.J. Galante gravitated toward hockey instead of football, as his father preferred, after seeing the 1992 movie The Mighty Ducks. Before being seriously injured in a game, the younger Galante had developed an aggressive style of play, modeled after his two favorite sports — ice hockey and professional wrestling. At one of A.J.’s childhood birthday parties, his father arranged for pro wrestlers The Rock, Triple H and Chyna to show up for the celebration.

A.J. has always looked up to his dad. When James Galante watched movies, for instance, he rooted for the bad guys. His son adopted the same philosophy.

This affinity for villains trickled over into the Galantes’ hockey team. By stocking the Trashers with outcasts and brawlers, and by encouraging on-ice fights, the father-son duo packed the Danbury Ice Arena with loud fans, attracting media attention from outlets such as ESPN and the New York Times that seldom give minor-league teams any attention.

The Trashers’ first player was Brent Gretzky, whose legendary brother, Wayne, is known as “The Great One.” In the documentary, Brent is referred to as “The Next Best One.”

The team’s roster included hard-hitters such as Rumun Ndur, “The Nigerian Nightmare,” who played in the NHL for the Rangers and other teams.

Another player who stood out for his rough play was Brad “Wingnut” Wingfield, whose many career injuries include nine broken noses and 300 facial stitches. During one of Wingfield’s game-halting fistfights seen in the documentary, blood droplets sprayed the ice, hitting a logo for Galante’s garbage company, Automated Waste Disposal.

Brosal referred to this collection of players and their antics as “a three-ring circus.”

Packed house

These days, Brosal stays in contact with James Galante. Not long ago, Galante phoned to ask if Brosal would appear in a 10-part series based on the Netflix documentary. “Absolutely,” Brosal told Galante.

In the end, the senior Galante is a loyal person who stands up for his family, Brosal said. “You’ve got to love a guy like that,” he said.

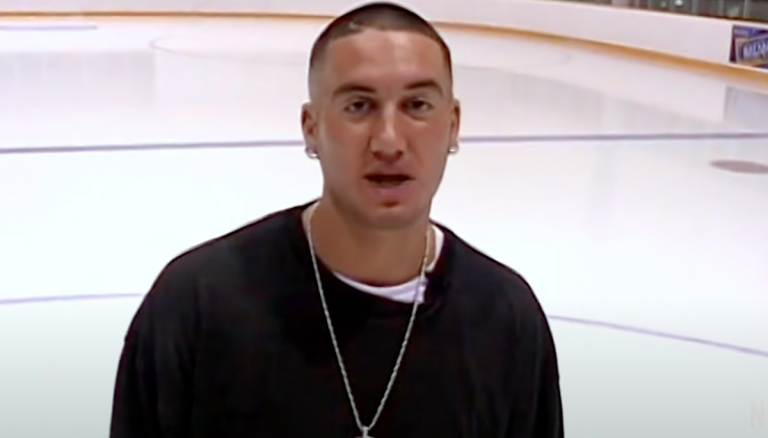

Even A.J., whom the commissioner once considered a diamond-earring-wearing punk, has matured, Brosal said.

Adams, who assisted Galante in his legal defense after retiring from the FBI, said hockey teams at all levels used to put brawlers on the ice. This included the NHL, where the Philadelphia Flyers, once known as the Broad Street Bullies, were infamous for roughing up opponents.

Galante simply tried to emulate that, Adams said. “His thinking was, ‘How are we going to get fans? We’ve got to have some muscle on the ice,’” Adams said.

The strategy worked. Crowds showed up. A raucous group of fans who sat in Section 102 at the Danbury Ice Arena became part of the team’s lore. Former NHLer Mike Rupp, who played for the Trashers during a lockout, said fans still remember him from his Danbury days — this despite his having scored a Stanley Cup-clinching goal for the New Jersey Devils.

Reflecting on his years as commissioner, and recalling the Trashers’ combative style, Brosal said, like it or not, the team generated a lot of publicity.

“Would I want that to be the legacy of the league? No,” Brosal said. “But say what you want, they packed the building every night.”

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org