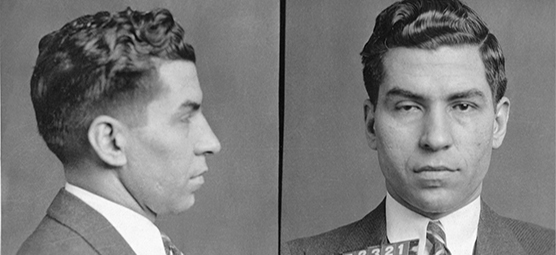

When Luciano’s luck ran out

Eighty years ago this month, a New York jury convicted Charles “Lucky” Luciano of pandering and sent him to prison

He told one of his cohorts, Florence “Cokey Flo” Brown, that he wanted to run his string of New York houses of prostitution on “a large scale, same as a chain store system.” Brown’s statement on the witness stand about her boss, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, during his 1936 pandering trial would help earn him a long stretch in state prison. Luciano, who practically created modern American organized crime in 1931 after arranging a hit on his own boss, was found guilty on a raft of prostitution charges on June 5, 1936. He was sentenced two days later and, on June 18, 1936, transferred to New York’s maximum-security Clinton prison in Dannemora. His criminal operation continued, but Lucky’s days as New York’s most flamboyant mobster were over.

Idolized and portrayed in iconic movies and television shows such as Boardwalk Empire and Mobster, Luciano was a larger-than-life figure. His trial began on May 13, 1936. Prosecutor Thomas Dewey exposed Luciano as a liar and accused him of participating in a prostitution ring known as “the Combination.” Testimony by star witness Brown, who was a drug addict, former madam and prostitute, and 27 other ex-working girls provided fuel for Dewey. Brown stated that she was told by an acquaintance about a madam who was beaten up by Tommy “the Bull” Pennochio on Lucky’s orders. Tommy was said to have stated “that the madam is in the hospital now.” During the trial, Luciano made the crucial decision to take the stand to defend himself and rebut the witnesses’ statements. He denied ever meeting the former “whores” who testified against him, even though a few had claimed to have been entertained at his luxurious suite in the Waldorf Astoria hotel. But disaster struck when he was cross-examined by Dewey, who questioned him about the lavish lifestyle he enjoyed on a reported income of just $22,500 per year. Dewey used phone records to prove Luciano made calls to notorious gangsters, including Louis “Lepke” Buchalter. Dewey’s tactics worked. It was enough to persuade the jury.

Luciano was convicted of more than 60 counts of compulsory prostitution and sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison. It was the longest sentence in history for compulsory prostitution. Luciano was the only New York Mob boss convicted during that time of a significant felony. The conviction solidified Dewey’s reputation with the press as a Mob-hunter. Even though “Cokey Flo” and two other former prostitutes used as witnesses later recanted their testimony, Luciano lost on appeal.

Luciano, born Salvatore Lucania on November 24, 1897, in Sicily, is considered the father of modern organized crime in the United States. He established the “Commission” in 1931 to unite the five major New York crime families and the Mafia’s criminal empire nationwide into a kind of corporation with him at the top.

Luciano immigrated with his family to New York when he was 9 years old. Trouble started early in his life with his involvement in teenage gangs. He soon had a rap sheet that included armed robbery, assault and gun possession. He landed his first prison sentence at age 18 after dealing heroin in New York’s Lower East Side in 1916. Luciano and Jewish gangster Meyer Lansky worked together in crime as young men. It is unclear how “Lucky” garnered his nickname but whether it was acquired for his success in gambling or for surviving gun and knife attacks, it seemed to fit.

Luciano became wealthy in the bootlegging business during Prohibition under the tutelage of Arnold Rothstein. He came to power with his involvement in the assassination of New York Mafia boss Salvatore Maranzano in the fall of 1931. Luciano orchestrated the murder after learning that Maranzano planned to have him killed. He then unified New York’s crime families with the “Commission,” a national governing board for the crime families to make decisions and prevent gang warfare. The New York bosses traveled to Chicago to meet with Capone and leaders of more than 20 other Mafia units. Luciano accepted some Old World traditions of membership but eliminated the previous requirement that Mafia leaders must be of Sicilian origin, allowing in syndicates led by Jewish and Irish bosses. Luciano believed that Mafia membership was a lifelong devotion and once stated, “The only way out is in a box.” With the business out of the way, the Chicago delegates reveled in the success of their meeting by enjoying a feast, jazz music and the favors of prostitutes.

By the end of Prohibition in 1933, the Mob shifted into other rackets, mainly gambling, loan-sharking and prostitution. Luciano’s own crime family began taking over New York’s organized prostitution during the early ’30s, though he was said to have despised of the business. “Cokey Flo” would later testify that he told her he planned to franchise houses of ill repute and thought about placing his madams on salary to prevent them from taking a cut from the working girls.

Luciano’s tenure as a wealthy and powerful Mob boss took a fateful turn in 1935. Eunice Carter, a social worker turned lawyer, was appointed assistant district attorney by Dewey, becoming one of the first African-American prosecutors in America. Dewey tapped her to work criminal cases at the Women’s Court in Harlem. While prosecuting women on prostitution charges, Carter noticed that many of the defendants used the same lawyers and bondsmen hired in Mob-related cases. She notified Dewey, who met with a judge in order to send a message to the Mob. The judge granted Dewey’s request to increase jail release bonds set for prostitution charges from the usual $300 to $10,000. Dewey then worked on holding three dozen alleged prostitutes and madams as material witnesses to bring down Luciano. Lucky left town to hide out in Hot Springs, Arkansas, but he was captured in 1936 and taken back to New York where he faced Dewey for the first time in April at a bail hearing. Judge Philip J. McCook, at Dewey’s urging, set bail at the then-enormous sum of $350,000.

After Luciano entered prison, everyday operations of the Commission’s families were handed over to his friend Frank Costello, known as the “King of Slots.” When Luciano’s appeals had failed by 1938, Costello assumed his position as head of the Commission. Costello’s takeover proved the wisdom of the managerial structure Luciano put in — the livelihood of the families was not endangered by the imprisonment of their boss.

After Dewey was elected governor of New York, he commuted Luciano’s sentence in 1946 in return for Luciano reportedly using his contacts in Sicily to aid the advance of Allied Forces during World War II. However, Dewey required that Luciano be deported to Italy. Luciano remained a respected Mafia leader from afar into the late 1950s, when he permitted his ally Carlo Gambino to lead the Commission.

Luciano died of a heart attack in Naples on January 26, 1962. He was 64.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org