Reader’s guide to Mob rub-outs

Anthony Destefano’s ‘Gangland New York’ mixes history and geography

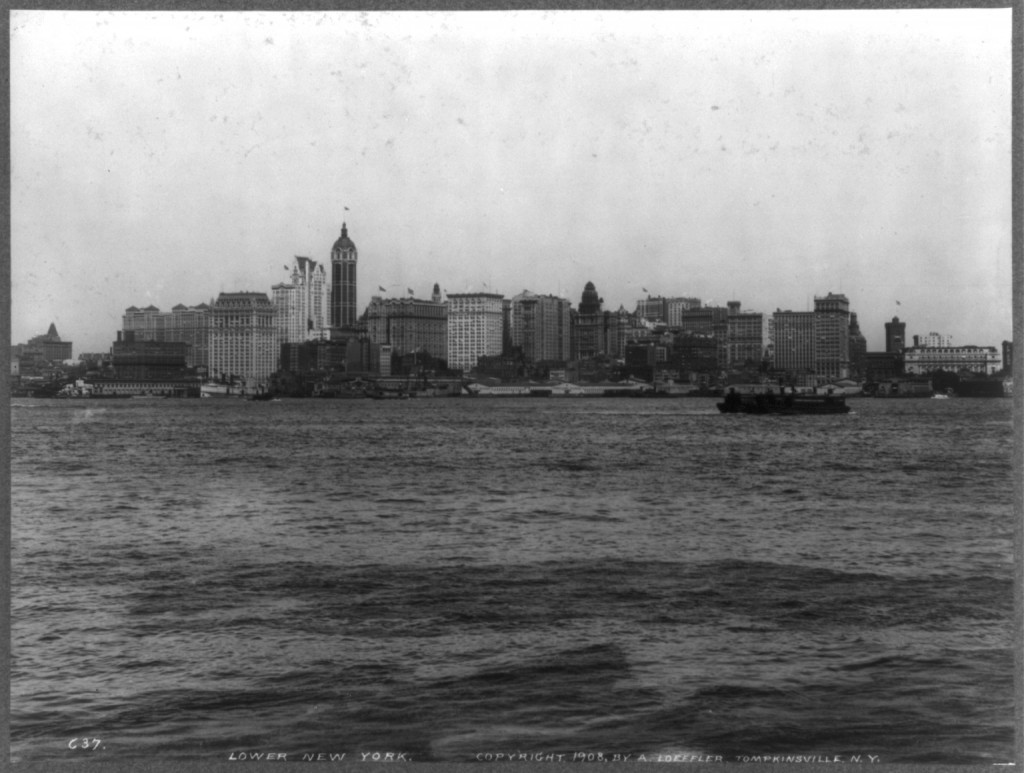

In New York’s long, rich history of organized crime, the death of Antonio Flaccomio is considered the city’s first Mafia slaying. It was in 1888, in the crime-infested Five Points district where immigrant English nativist and Irish street gangs such as the Bowery Boys, Dead Rabbits and Whyos had fought decades earlier. Now, immigrants from Italy and Sicily dominated Five Points.

Flaccomio, a cigar dealer and associate of Sicilian mobsters, had narrowly escaped conviction in the murder of a tobacco merchant in 1884. On the evening of October 14, 1888, Flaccomio was playing cards at a restaurant at 8 St. Marks Place when he got into a fierce row with others in the game. He left, and while walking about a block west near the Cooper Union building at East 8th Street and Third Avenue, two of the card players, brothers Carlo and Vincenzo Quartararo, confronted him. Carlo fatally stabbed Flaccomio in the chest. The brothers rushed back to the eatery and asked everyone to keep quiet.

Using street view from Google search, the corner by the Cooper Union in East Greenwich Village where Flaccomio was stabbed can be viewed in full color, as can the still-surviving 1870s building at 8 St. Marks Place where he had his last card game and now stands next to a karaoke bar.

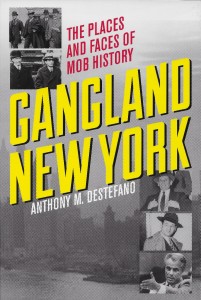

Finding the precise locations of more than 100 underworld rub-outs – and in some cases, grave sites — in New York’s five boroughs can be addicting thanks to Anthony DeStefano’s new book, Gangland New York: The Places and Faces of Mob History. DeStefano discussed his book on May 11, 2016 at The Mob Museum.

DeStefano’s book is a sort of Baedeker’s guide to Mob killings in the city, and knowing just where they unfolded adds to the (grisly) fascination with organized crime in New York, from the 1840s to the rise of the city’s infamous “Five Families” in the early 20th Century to the 2000s. The book ends with Wall Street scammer Bernie Madoff heading – alive – toward prison from the federal court in Manhattan by present-day Columbus Park in 2009. It was ironic, DeStefano wrote, that his “last walk as a free man was over the pavement at the old Five Points.”

The author covers the classic Mob hits, and misses, in New York, frequently committed in public in front of witnesses:

– Luciano Mafia boss Frank Costello’s near demise by a shooter who said “This is for you, Frank,” before wounding Costello in the lobby at 115 Central Park West on May 2, 1957.

– Brooklyn boss Albert Anastasia’s deadly fall from a barber chair in a hail of bullets inside the Park Sheraton hotel at Seventh Avenue and Fifty-Fifth Street on October 25, 1957.

– Joey Gallo, a Profaci family member who wanted to start a “sixth” Mafia family to the five existing ones in New York, murdered in front his wife and daughter while dining at Umberto’s Clam House at the intersection of Hester and Mulberry streets on his birthday, April 7, 1972.

– Gambino family chieftain Paul Castellano, cut down along with his driver by two gunmen before his intended dinner outside Sparks Steak House at 210 East Forth-Sixth Street in Manhattan on December 16, 1985.

Some of New York’s most famous contract killings occurred in the late 1920s, during the height of the city’s illegal booze racket. One was ordered by former New York-based gangster Al Capone on his friend and fellow bootlegger Frankie Yale, shotgunned to death in traffic before his car crashed at 923 Forty-Fourth Street on July 1, 1928. Mafia boss Salvatore D’Aquila was cut down while waiting for his wife at Avenue A and Thirteenth Street on October 10, 1928. Gambler, bootlegger and Mob diplomat Arnold Rothstein was mortally wounded in his room at Fifty-Sixth Street and Seventh Avenue on November 4, 1928, and died two days later.

The slayings of two old-school Sicilian Mafia leaders months apart in 1931 would set in motion a new, modern era of organized crime not only in New York but throughout the United States. In the midst of a major power struggle for Mafia control known as the Castellammarese War, top Mafia boss Joseph Masseria started killing allies of rival Sicilian boss Salvadore Maranzano in 1930. Maranzano countered with hits on Masseria’s crew. Masseria wanted more war. But one of Masseria’s top young lieutenants, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, had his own ideas, decided to switch sides and betray his boss. On April 15, 1931, Luciano set a trap for Masseria at the Nuova Villa Tammora Italian restaurant at 2715 West Fifteenth Street on Brooklyn’s Coney Island. After lunch and cards, Luciano went to the men’s room, two gunmen appeared and shot Masseria multiple times.

When Maranzano assumed power, his plan to have Luciano, Capone and other key gangsters killed leaked out. Luciano contacted Meyer Lansky and Longy Zwillman to hire assassins, who ambushed and eliminated Maranzano at the boss’s ninth-floor office at 230 Park Avenue on September 10, 1931. Luciano then took over as boss, but not like the old days. He founded a new structure for the Mafia — the “Commission” composed of the five major Mafia families of New York and groups in Buffalo, Chicago and other cities as well. And unlike the dead bosses, he worked with non-Sicilians and non-Italians. All agreed to settle disputes in peace instead of war and pursue making money like a corporation.

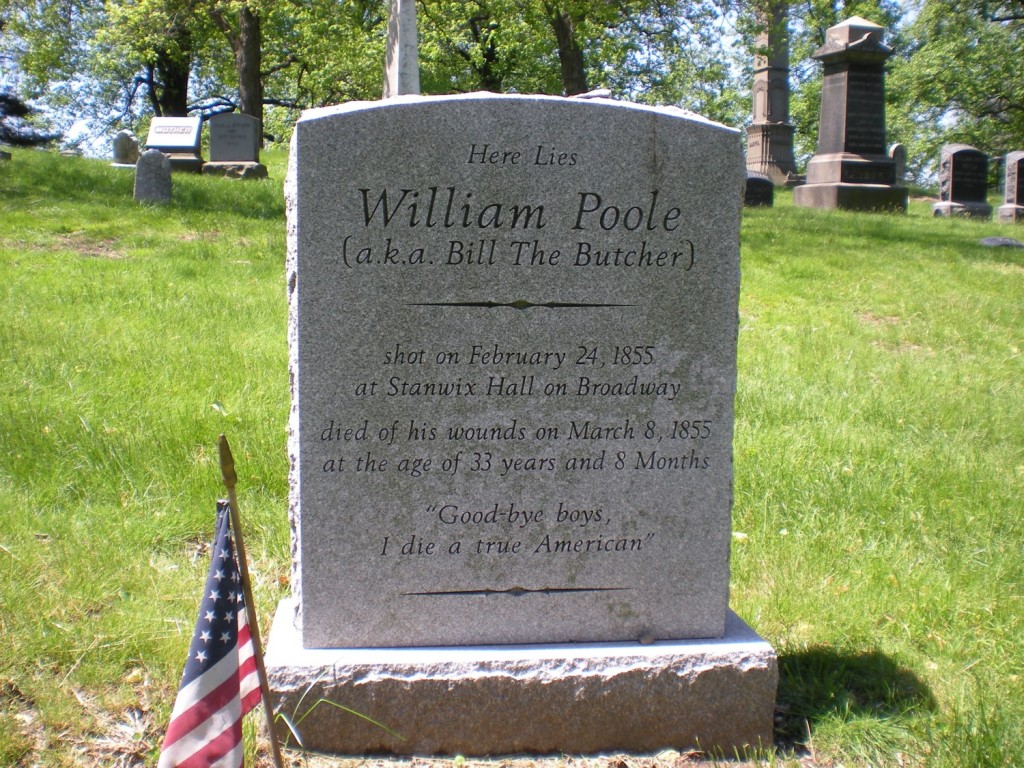

DeStefano also covers the early years of the New York’s 175-year legacy of underworld violence and death. The brutal chief of the Bowery Boys gang in Five Points, William “the Butcher” Poole, a character portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis in Martin Scorsese’s 2002 movie Gangs of New York, was shot at Stanwix Hall at 579 Broadway in Lower Manhattan in 1855. Poole died a couple of weeks later at his home at 164 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. Poole was not just prone to violence. He was among the first mobsters who sought to influence city politics to his advantage. At one time, there were perhaps 30,000 gang members in New York, and large inter-gang brawls of up to 1,000 people left dozens injured as police stood by unable to stop it.

With the Sicilian immigrants in the late 19th Century came the “Black Hand,” a Mafia group victimizing Sicilian and Italian business owners through extortion – forcing merchants to make cash payments under threat of violence. After the turn of the century, Jewish immigrants entered the fray, including Monk Eastman, leader of his gang called the Eastmans. Their roost was at Allen and Rivington Streets on the Lower East Side. Eastman was known as a violent, intimidating street hood, unlike his rival, Paul Kelly, an Italian whose real name was Paolo Vaccarelli who oversaw the Five Pointers mob. The inevitable clash on the street between the gangs came the evening of September 16, 1903, and lasted for hours into the next morning. Rival members exchanged gunfire at the northwest corner of First Avenue and First Street, and the public shootout carried over to Eastman turf on Allen and Rivington. About 50 gangsters took part, two died and Kelly was among the wounded. The two leaders agreed to a truce. Kelly died of natural causes in 1936, but Eastman was shot dead in a café at 62 East Fourteenth Street in 1920 by a Prohibition agent after an argument. His death, followed by a large funeral procession toward Cypress Hills Cemetery at the border of Brooklyn and Queens, signaled the end of large “gangs” of New York based on loyal comradeship and the emergence of smaller groups focused on running rackets for profits.

One lesser-known but interesting New York hit was meted out in 1959 to high-ranking Mob capo Anthony “Little Augie” Carfano, a buddy of Capone’s during Prohibition and stalwart to boss Frank Costello. Carfano apparently offended Vito Genovese by not showing up for a meeting when Genovese took over as boss after Costello was wounded in 1957. Augie was with Janice Drake, the pretty former Miss New Jersey married to so-so nightclub comic Allan Drake, whose career Carfano propped up with bookings at top Mob-run venues such as Costello’s Copacabana in New York and the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas.

On September 25, 1959, while Allan was playing a gig in Washington D.C., his leggy blond wife was nightclubbing at the Copacabana. The club was a known haunt for gangsters, and Janice liked to hang with them. She was on a date with Garment district mobster Nat Nelson in 1952 the day before Nelson was killed. She went out to dinner with Anastasia the night before his death. This evening she left her 13-year-old son at home, put on a fur wrap and went out with a girlfriend to the Copa where they met Carfano, who proposed they go to a restaurant. Later, Carfano got a phone call and told Janice to get into his Cadillac. It was a fateful decision, but Carfano was her and her husband’s meal ticket. They drove to a hotel near LaGuardia Airport about 9:30 p.m., then left quickly.

About 10:30 p.m., at 24-50 Ninety-Fourth Street, neighbors heard gunshots. Police found Carfano’s caddy stopped with the engine and lights on. Carfano and Mrs. Drake were both dead, shot in the head from behind. The culprit or culprits, likely in the back seat, bolted. The crime was never solved. Some believe the order came from Genovese over Carfano’s slight. Others say it was via Lansky and Santos Trafficante over Carfano’s desire to open competing rackets in Florida. As for Mrs. Drake, a suspected Mob courier, it was her last time hanging with the wrong crowd.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org