The Top 5 Mob myths: Hollywood’s creative license drives misinformation

The truth behind the most repeated falsehoods surrounding organized crime

From The Godfather to Griselda, the Mob is firmly embedded in pop culture, which comes with a few drawbacks. In a medium that prioritizes entertainment over education, misconceptions are bound to spread, often becoming promoted to conventional wisdom. Budding mobsters have even been influenced by film and television in the way they see and conduct themselves.

Myths propagated by pop culture have built the image of the Mob into a powerful, yet honorable, organization, detached from its real-world counterpart. Hidden behind these false premises are kernels of truth, however, so let’s dive into the five most common Mob myths to distinguish fact from fiction.

5. The Mob doesn’t kill civilians

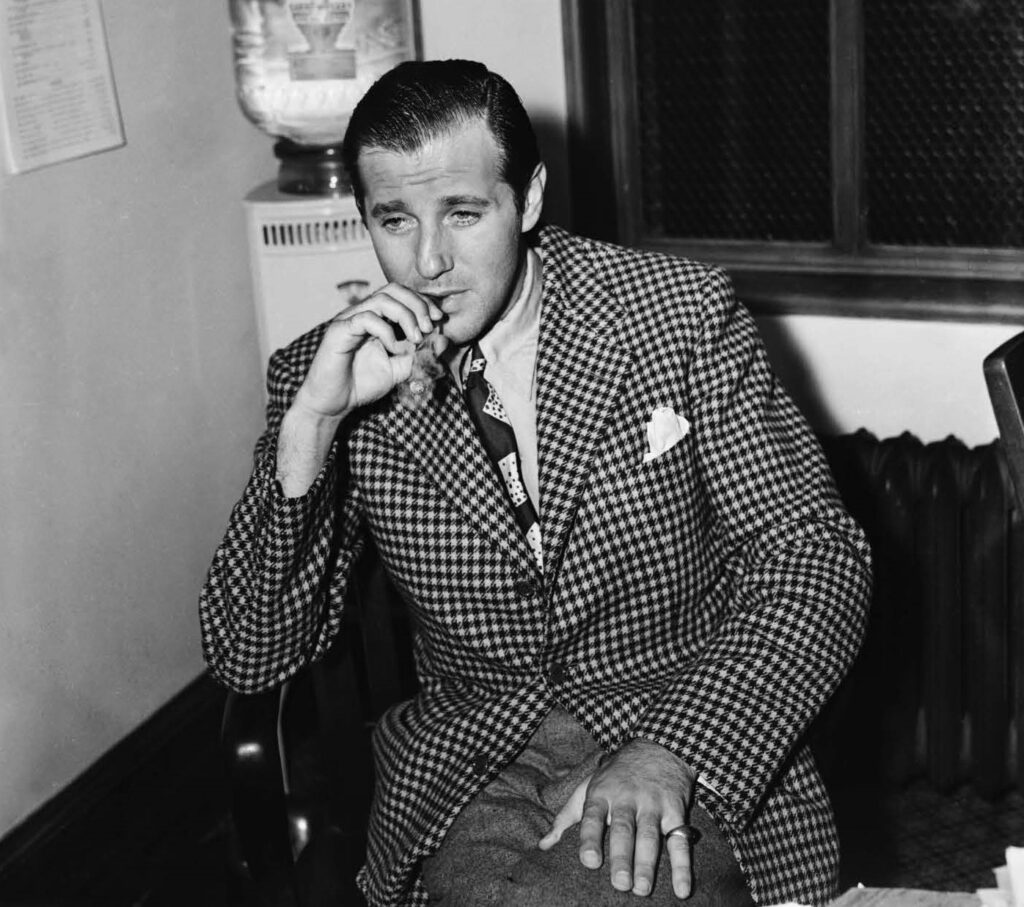

“You’ve got nothing to worry about, Del. We only kill each other.” — Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, Bugsy (1991)

When Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel took control of the Flamingo Hotel project in Las Vegas, he hired Del Webb to oversee construction. Webb quickly learned of Siegel’s reputation from the man himself. When Siegel boasted that he had personally killed 12 men, Webb became understandably nervous. Siegel dismissed his concerns by saying, “We only kill each other.” Meaning, the only targets are those who have chosen that way of life. But is that really true?

Contrary to Siegel’s claim, civilians are quite often caught in the crossfire of Mob violence. In 1982, Michael Donahue offered to give an old friend a ride home from a Boston bar. Donahue was unaware that Brian Halloran, an FBI informant, had been marked for death by James “Whitey” Bulger. Bulger and an accomplice drove up alongside Donahue’s Datsun and began shooting. After the car crashed, Bulger made sure that the two were dead. More than 30 years later, Donahue’s murder was among the 11 counts that gave Bulger two life sentences.

Collateral murder is not unique to American organized crime. In 1992, on a highway in Capaci, Sicily, magistrate Giovanni Falcone and his wife, Francesca Morvillo, were returning home when an explosion killed them and three police escorts. Members of the Sicilian Mafia had used a skateboard to move 500 kilograms of TNT and ammonium nitrate into a drainage pipe beneath the road. This method of deployment, Mafia informant Maurizio Avola claimed, came from an explosives expert sent by John Gotti.

Whether through mistaken identity, collateral damage or loose ends, the Mob will kill whoever it wants, regardless of an individual’s involvement in the underworld.

4. The Mob doesn’t deal drugs

“But drugs, that’s a dirty business.” — Don Corleone, The Godfather (1972)

This misconception originated from the Mob itself. “I did not tolerate any dealings in prostitution or narcotics,” wrote New York boss Joseph Bonanno in his autobiography A Man of Honor. “Perhaps other families didn’t adhere to my strict guidelines, but this was my way.” But what people say and what they do are often two different things.

Evidence of drug trafficking is peppered throughout the early history of organized crime, well before Bonnano collaborated with the Sicilian Mafia in 1957 to import heroin. Illegal drug trafficking in American organized crime is as old as the first federal anti-narcotics law in 1915. Throughout the 1910s, opium dens were frequently mentioned alongside brothels and gambling joints run by Big Jim Colosimo’s gang, the precursor to the Chicago Outfit. In New York, Charles “Lucky” Luciano received his first conviction in 1916 for selling heroin, landing him six months in jail. Decades later, Luciano would play a key role in recruiting Sicilian mafiosos as street-level drug dealers for New York, shielding American mobsters from the consequences of heroin trafficking.

Bad publicity and lengthy prison sentences were enough of a deterrent for a few bosses to discourage dealing drugs. Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, a founder of Murder Inc., was sentenced in 1940 to 14 years in prison for his heroin trafficking ring. Vito Genovese, namesake of the Genovese crime family, landed 15 years in prison in 1959 for narcotics trafficking, effectively a life sentence for the aging mobster.

Gambino boss Paul Castellano was one of the few who truly banned drug trafficking. His rule left no room for interpretation, “You deal, you die.” The new generation of wiseguys, including John Gotti, did it anyway. Castellano might have killed Gotti for violating his cardinal rule, but Gotti killed him first. While Gotti managed to skate by drug charges (instead getting life for murder in 1992), his brother, Gene Gotti, was not so lucky. He was sentenced to 50 years for narcotics trafficking in 1989.

Despite heavy consequences, drug trafficking has remained a staple in organized crime rackets worldwide. In that world, money trumps morals.

3. The Mob started Las Vegas

“That kid’s name was Moe Greene, and the city he invented was Las Vegas.” — Hyman Roth, The Godfather: Part II (1974)

The way the movies tell it, Las Vegas was a dilapidated gambling burg in the middle of the Mojave Desert when Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel (the inspiration for Moe Greene) swooped in to transform it into a resort metropolis. In truth, Las Vegas had been steadily growing since its birth as a railroad town in 1905. In 1931, the construction of Hoover Dam set the infrastructural stage for a booming population. Casinos became widespread after the statewide legalization of gambling the same year. By the time Siegel set foot in Las Vegas, it was already a flourishing city.

When the first New York mobsters arrived in Las Vegas, there were already two casinos on the Strip, the El Rancho Vegas and the Last Frontier. At the time, Hollywood Reporter publisher Billy Wilkerson was constructing the Flamingo, but turned to the Mob’s financing when he ran out of money. Siegel joined on as the Mob’s representative, although he later forced Wilkerson out to finish the project himself. Plagued by overspending, the Flamingo had a disastrous opening month when the rooms weren’t ready for guests. His financial mishaps roused suspicions of theft from his financiers, which led to fatal consequences on June 20, 1947, when he was murdered in Beverly Hills.

There is usually an ounce of truth in what the movies depict. The Mob did bring a level of luxury that wasn’t seen in the Western-themed casinos of the Strip’s early years. Even taking mismanagement into consideration, the $6 million the Mob sunk into the Flamingo’s construction dwarfed the El Rancho Vegas’s price tag of less than $500,000. While the town had already been around for decades, the Mob brought with it the gambling and entertainment expertise to morph Las Vegas into the entertainment capital of the world (although they would skim from the profits every step of the way).

2. The Mob helped elect John F. Kennedy

“It was easy for the Mob to help Joe Kennedy get his son elected president by making sure he won in Illinois.” — Frank Sheeran, The Irishman (2019)

It’s true that for much of the early 20th century, organized crime had some influence on the political machines that dominated large urban centers, such as New York City’s Tammany Hall. However, that influence began to wane as investigations and Senate hearings revealed political corruption to the public.

There are rumors that Joseph P. Kennedy approached Chicago mobsters and asked for their help in getting his son elected. But the data do not support this claim. When John F. Kennedy ran for the Democratic Party’s nomination in 1960, the Chicago Outfit’s influence only spread to five of Chicago’s 50 wards. The Outfit, its manpower diminished since the Capone days, didn’t have the numbers to intimidate voters throughout their five wards. In addition, a statistical analysis of votes in the 1960 election by Chicago Mob historian John J. Binder showed that voting trends in the Outfit’s historically pro-Democrat wards followed similar trends to the rest of Chicago. There is evidence that the Outfit labored to influence a down-ticket state’s attorney election, but irregularities drew suspicious on only about 6,000 out of 490,000 ballots cast.

What did have the power and influence to tip the scales in Kennedy’s favor, however, was Mayor Richard Daley’s Democratic machine. Daley and his cronies used significant resources to deliver votes for their candidate.

To their credit, the Chicago Outfit did have the ability to influence Chicago’s elections, especially when a Republican candidate campaigned on organized crime crackdowns. The Outfit’s wards show statistically significant voting trends heavily in favor of Daley in the 1955 mayoral election. Daley’s reformer opponent, Robert Merriam, became a threat to the Mob after he vowed to end Chicago’s tolerance of racketeers.

Things might have been different if the Outfit knew just how much of a threat Kennedy posed with his brother Robert at his side. In the lead-up to the 1960 election, the soon-to-be attorney general had already been grilling mobsters and corrupt Teamsters Union boss Jimmy Hoffa as chief counsel of Senator John McClellan’s hearings on labor racketeering.

1. The Mob assassinated President John F. Kennedy

“Ruby’s all Mob, knows Oswald, sets him up. Hoffa — Trafficante — Marcello, they hire some guns, and they do Kennedy.” — Bill Harvey, JFK (1991)

Who hasn’t been suspected of involvement in the 1963 assassination of President Kennedy? Those named in conspiracy theories on and off the grassy knoll include the KGB, Secret Service, CIA, pro-Castro groups, anti-Castro groups, President Lyndon Johnson and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover — and that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Mob bosses Sam Giancana, Santo Trafficante and Carlos Marcello have also been thought to have been involved in killing the president.

The so-called evidence of the Mob’s involvement lies primarily with Jack Ruby, the man who killed Lee Harvey Oswald two days after the assassination. By virtue of being a nightclub owner, Ruby certainly had contact with members of organized crime. However, these were not close connections, in particular because of his past. Born in Chicago, Ruby was an errand boy for the Mob on the West Side of Chicago. Yet according to Mob historian Gus Russo, Ruby was run out of Chicago because he was frequently interviewed by police to inform on the Mob. This is not the kind of person that a high-ranking mobster would trust to take care of loose ends.

It’s certainly true that some mobsters had a beef with Kennedy. With Robert F. Kennedy serving as his attorney general, the brothers went after organized crime. Tampa Mafia boss Santo Trafficante Jr. allegedly gave a toast in private to his lawyer, hours after the assassination. Yet, the Mob was still an organization that operated best with minimal attention from the law. High-profile assassinations were out of the question. When New York bootlegger Dutch Schultz suggested that he would take out District Attorney Thomas Dewey in 1935, Mafia leadership promptly had Schultz killed instead.

The Mob exists primarily to make money. To kill a president of the United States would bring on the full wrath of American law enforcement, a move that would inhibit them from fulfilling their raison d’être.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org