The 1863 draft riots and the birth of the New York City Police

Depicted in the 2002 film ‘Gangs of New York,’ the riots forced the police to organize

On July 13, 1863, during the Civil War, New York City burst into flames when the federal government started a draft. Residents, especially poor immigrants, were inflamed at the possibility of serving. The city’s police force became the target of their anger.

Reports of the situation rang out around the country. The Daily State Gazette of Trenton, New Jersey, reported, “Two o’clock – The riot is said to have assumed vast proportions … the police have been handled terribly severe. It is reported that Police Superintendent Kennedy and some 15 of the police were killed and many wounded.” As the riots ensued over the course of a week, the police had to coordinate their efforts quickly to end the violence.

The 1863 draft riots made their way into the modern psyche with Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film Gangs of New York. The film, which highlights the rise and fall of New York street gangs, is loosely based on The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld, a nonfiction book by Herbert Asbury published in 1927. The end of the film features the draft riots but takes creative liberties with the details.

The real story highlights the challenges and corruption involved in creating a police force in New York. The newly formed law enforcement agency would almost inevitably clash with the working-class immigrant groups that had been growing in New York throughout the 19th century.

New York Police in the 1850s

The New York City police first organized in 1853 when the state mandated uniforms and established a supervisory commission. Democratic Mayor Fernando Wood corrupted the commission, however, when he cajoled members to give him sole power over the police. In 1857, the Republican Party gained control over the state government and created a new force, the Metropolitan Police. Wood, however, refused to give up his police force, which he called the Municipals. The city now had two police forces with a distinct ethnic divide: the Municipals, mostly Irish Catholic immigrants, and the Metropolitans, primarily Anglo-Saxon Protestants.

In Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, historians Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace wrote about the two forces, “Chaos ensued. Criminals had a high old time. Arrested by one force, they were rescued by the other. Rival cops tussled over possession of station houses.” After a fight outside City Hall, the state’s Court of Appeals ruled the Metropolitans as the city’s legitimate police force. The decision forced Wood to disband the Municipals the day before a major riot on Independence Day.

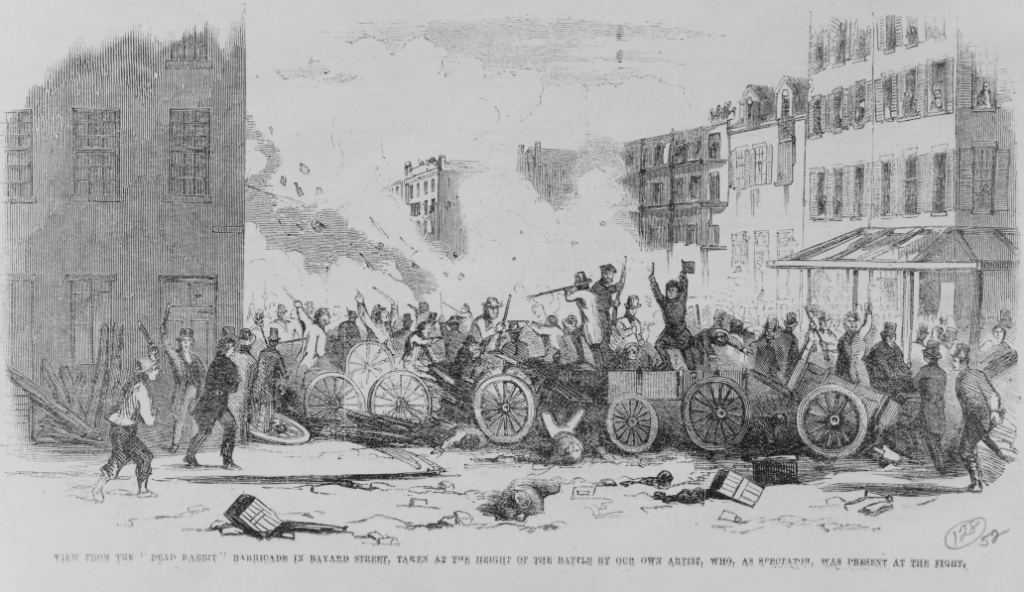

The Wood-aligned Dead Rabbits, an Irish Sixth Ward gang, caught the weak Metropolitans off guard with an assault amid the festivities. Luckily, a rival gang affiliated with the Know-Nothings, a political party consisting of anti-immigrant, Protestant-leaning Bowery Boys, came to the police’s rescue. These gangs of mostly young laborers and apprentices had ruled respective neighborhoods since the 1830s. However, these groups, far from organized, were more like raucous social groups for young men. The clash between the gangs allowed the police to beat a retreat, but order was not restored until the National Guard arrived. Twelve people were killed, including two police officers, and 41 others were injured.

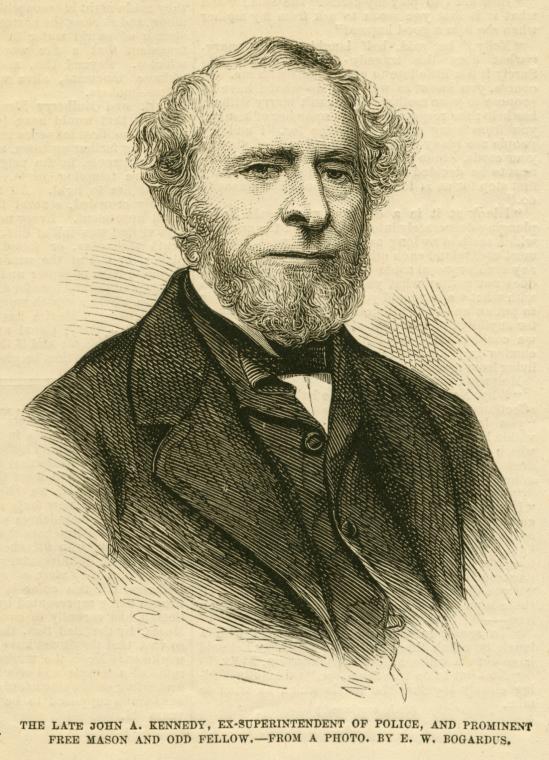

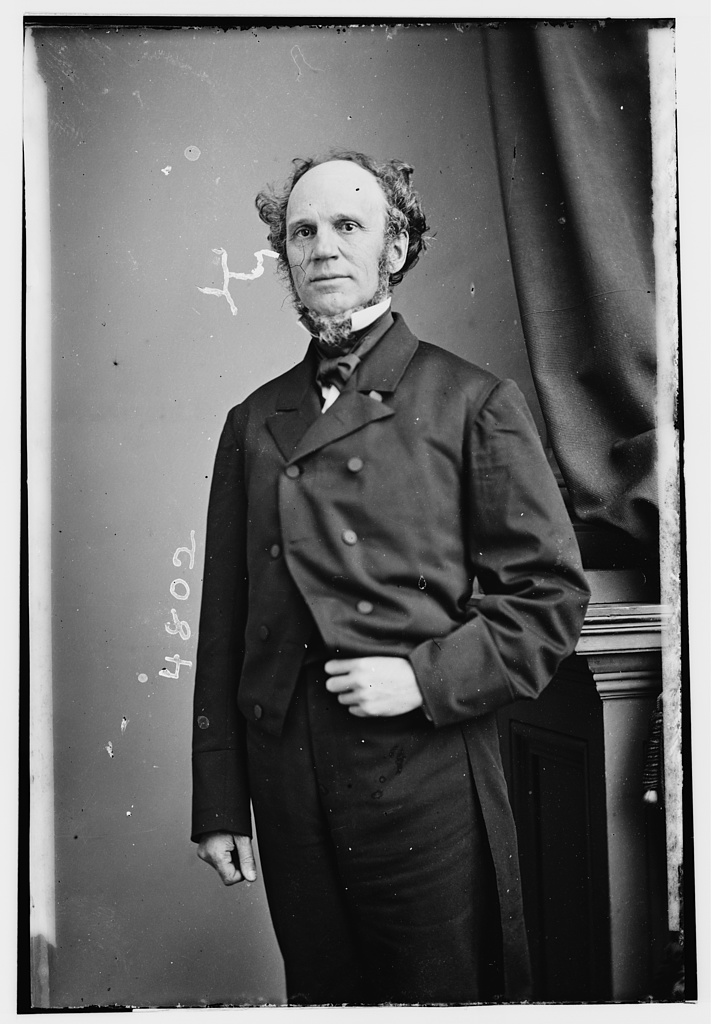

The new superintendent

Political forces continued to interfere with the police until John A. Kennedy became the new superintendent in May 1860. Kennedy allowed former Municipals to rejoin the force. The attempt to conciliate incensed Irish Catholics failed, however, because the Metropolitans continued to target immigrants. In one day in 1860, Metropolitans arrested 500 “street vagrants,” mostly immigrants, for the vaguely defined crime of “disloyalty to the Union.” Kennedy also used his powers during the Civil War to arrest 4,000 army deserters in a single year, again mostly immigrants. During the 1862 midterm elections, his officers singled out immigrant voters in a ploy to keep them from the ballot box.

In that same year, Kennedy arrested a well-respected member of the immigrant community, Isabel Brinsmade, for treason. Her arrest triggered a major backlash, and she sued Superintendent Kennedy and the Metropolitan Police for unlawful arrest. During the trial, evidence and testimony showed the police commissioners that Kennedy had been overzealous in his duties. Yet, the commissioners stirred more animosity by only censuring him.

More tinder for the riots

The ill-prepared police had other issues leading up to the draft riots. Without a riot squad or even mounted police officers, they relied on “direct attack on the mob, with a vigorous use of the club,” wrote historian Adrian Cook in The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863.

The force also lacked support from state leaders. Democratic Governor Horatio Seymour sunk police morale with his constant criticism. Seymour attempted to replace the Republican members of the Board of Commissioners with loyal Democrats.

Invading Confederate troops at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, made tensions worse and the need for conscripts more apparent. Around the same time, the federal government began to implement the National Conscription Act. Immigrant workers despised the new law because wealthier men could pay $300 to dodge the draft, far above a working-class immigrant’s pay grade. Beyond that, President Abraham Lincoln had stipulated there were no exemptions for immigrants working toward citizenship.

With low police morale, limited peacekeeping ability and agitated immigrants, the city only needed a match to set it ablaze.

The match

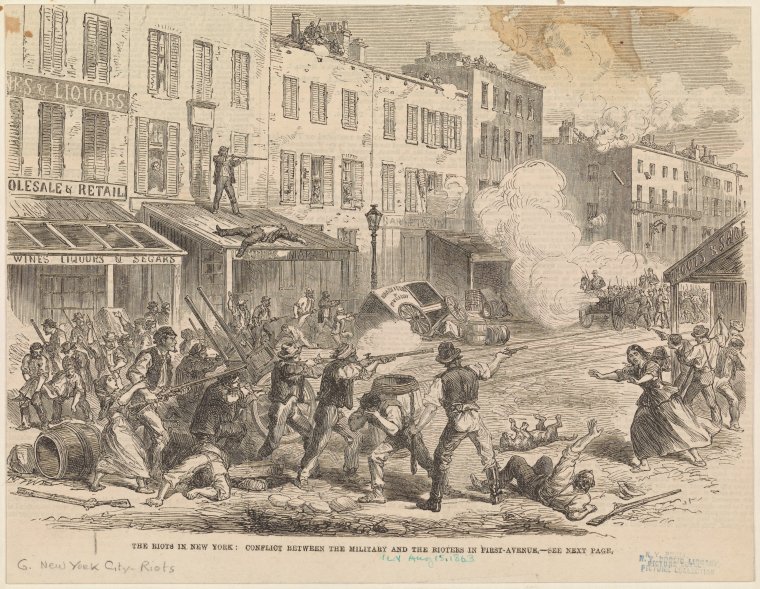

On the morning of Monday, July 13, 1863, draft workers began to draw names. Laborers around the city skipped work to protest. One group marched to the Ninth District Provost Marshal’s Office, where the draft was taking place. Draft officers had only announced about 50 names when the angry mob descended.

The firemen of the Black Joke Engine Company No. 33 joined the mob, incensed that their captain had been drafted. The immunity that kept firemen in the city from being drafted into the state militia apparently did not apply to the Union army. “A pistol shot rang out, and the Black Joke men burst into the office, smashed the selection wheel, and set the building on fire,” wrote historian Iver Berstein in The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War. The draft riots had begun.

Assault on the police and Superintendent Kennedy

All hell broke loose, and the angry mobs took their frustrations out on the Metropolitan Police. Rioters targeted the homes of officers or those sheltering them. Captured policemen were stripped of their uniforms and beaten, if not killed. In one particularly gruesome instance, a woman attempted to cut off the ear of a badly beaten officer, but squeamish rioters prevented her from finishing the job. Doctors were later able to reattach his ear.

The major target for the rioters was the despised police superintendent. When Kennedy heard about the rioting, he left police headquarters and made his way to the scene. He rode in a buggy until he hit blockaded roads and proceeded on foot. As he walked up Lexington Avenue, a former cop recognized him, “Here comes the son of a bitch Kennedy! Let’s finish him!”

The crowd pounced on Kennedy and beat him over the head until he was unrecognizable. The attack left the police with no leadership for hours. Some newspapers reported Kennedy was dead. Eventually, Police Commissioner Thomas C. Acton took control of the situation and called on all police units to converge at police headquarters on Mulberry Street.

When Kennedy was finally found, he “was almost unconscious, his face fearfully bruised and cut, one eye entirely closed, lips swelled frightfully … his hand cut with a knife, his body a mass of bruises, and his person covered with blood and mud,” according to contemporary historian David M. Barnes in The Draft Riots of New York, July 1863. The 60-year-old superintendent survived the riots and continued as superintendent until 1870, but for the rest of the week he was out of commission.

Siege and arson

Continuing the first day’s violence, a clash occurred between the Metropolitans and rioters at the Upper East Side Union Steam Works located on East 22nd Street. The factory, owned by the son-in-law of Republican Mayor George Opdyke, had been commandeered as an armory. There, police engaged in hand-to-hand combat with rioters. After three attempts, the rioters routed the police. Soldiers in the 12th U.S. Infantry broke through the rioters to recover the remaining arms cache.

The following evening, the steam works were burned to the ground. The nearby 18th Ward Police Station and the 23rd Precinct were also set ablaze. Days later, women and children were scavenging the remnants of the 18th Ward building for wood and other supplies when it collapsed, killing three of them.

During an assault on Jackson’s Foundry on July 15, two days into the riots, the mob demanded that the soldiers guarding the building give up all police officers within. The soldiers — unwilling to adhere to the rioters’ demands — were quickly overtaken. The foundry, however, was saved from destruction by military reinforcements who drove the rioters away. The police were clearly being targeted, but they weren’t the only group facing the mob’s wrath.

Black community targeted

The Black community was the rioters’ other major target. Anger within the immigrant community toward Black residents had escalated weeks before the riots. Factory owners had used Black workers as strikebreakers, guarded by the police. This touched off violence against the Black community in the city. The violence leading up to the riots was so bad that Superintendent Kennedy warned Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that he should not march the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, the first all-Black regiment, through the city.

During the riots, the police neglected to aid the Black community. In one instance, the police arrived far too late to aid a Black mariner named William Williams, who, after asking for directions, was murdered by whites near the uptown docks. Later, the police arrived upon the corpse of a Black coachman named Abraham Franklin hanging from a lamppost. Although the police took his body down, they callously left him lying in the street for the mob to desecrate.

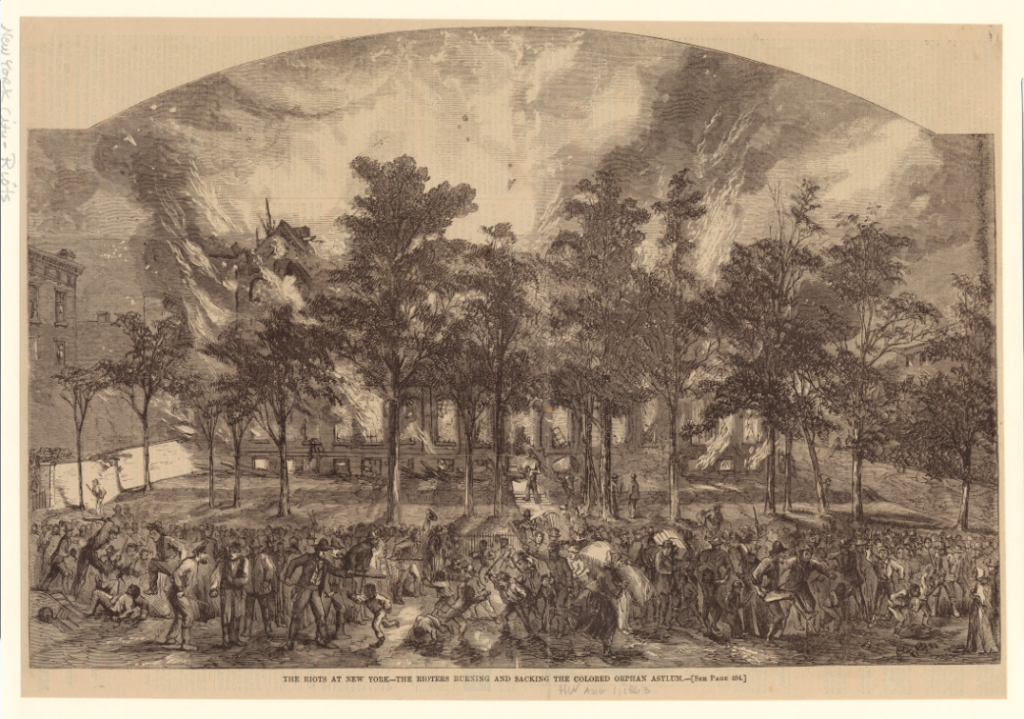

The rioters’ carnage continued by burning down the Colored Orphan Asylum. Luckily, an Irish driver of a horse-drawn omnibus rescued the children and transported them to safety at a police station.

Control returns

The police and military slowly gained control over the situation. However, they received no assistance from Governor Seymour, who arrived in the city on Tuesday morning. He declined to declare martial law and referred to the rioters as his “friends.” Furthermore, Irish Catholic Archbishop John Hughes, the most prominent member of the Irish community, remained silent on the situation until the chaos subsided.

It was through the efforts of Commissioner Acton and military leaders that order returned to the city. After Acton regrouped the police at headquarters, he placed Senior Inspector Daniel Carpenter in charge of forces. Carpenter led officers to the street outside and rallied the gathered officers, “Men! We are to meet and put down a mob. We are to take no prisoners. We must strike quick and strike hard.”

They soon won major victories. The forces dispatched a mob that attacked Brooks Brothers Clothing Store on Catherine Street and, with military support, broke down a barricade on Ninth Avenue placed by rioters. By Thursday, the situation was almost under control when more soldiers arrived from Gettysburg and patrolled the streets around Gramercy Park with a howitzer. By Friday, about 6,000 troops and other Metropolitan officers were stationed around uptown, and calm began to return to the city.

Aftermath of the riots

The bloody riots claimed more than 100 lives. The destruction was felt in more than 50 burned buildings and damages close to $2.5 million (about $53 million today). The riots led directly to efforts to professionalize both the police and fire departments.

After the Black Joke Fire Company sparked the riots, Superintendent Kennedy and Commissioner Acton called for major reforms. Two years after the riots, state legislators transformed the fire companies from voluntary social groups into salaried city employees. The police put more focus on mob suppression with more drills and club training, according to historian Adrian Cook.

The riots forced the police to quickly organize themselves to curb violence across New York City. Officers soon had training manuals and physical training standards to prepare for future situations. Officers, armed with just a club to keep the peace during riots, learned how to use the tool effectively. New York City Police still carry clubs in the form of a collapsible aluminum baton.

Martin Scorsese brought the riots into popular culture with Gangs of New York. The movie features events from the draft riots, but the story contains historical inaccuracies. In reality, the gangs had little to do with the draft riots, and William “Bill the Butcher” Poole, portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis, died eight years before.

Timothy Brown is a Ph.D. student in history at the University of Connecticut. He received his master’s degree in history from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He served as an intern at The Mob Museum in 2021.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org