The top 5 heists in Mob history

Organized crime figures lurk behind some of America’s biggest robberies of the 20th century

What makes a “good” heist? Is it an exceptionally detailed plan, a cast of colorful characters or an unfathomable amount of stolen money or goods?

Armed robberies have never been the bread and butter of organized crime activities, but the Mob has been involved in some large, high-profile heists over the past century. Here are the top five heists in Mob history, selected for their strong Mob ties, incredible stories and the exceptionally high value of the stolen goods.

5. Plymouth Mail heist, Plymouth, Massachusetts

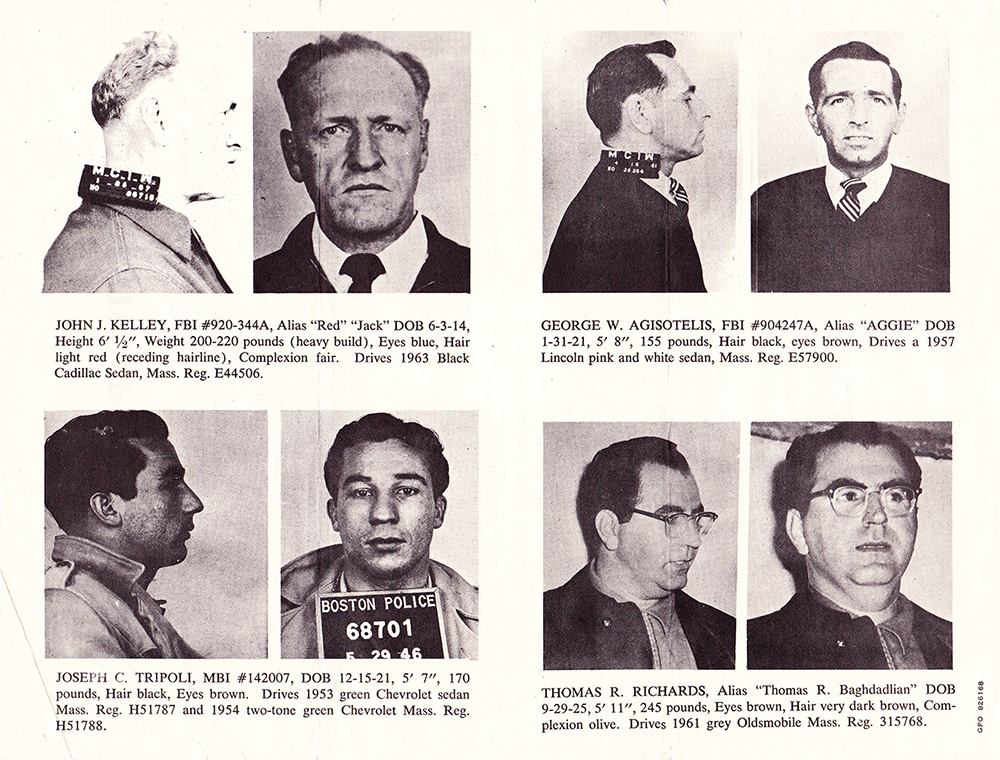

In what the press dubbed the “Great Plymouth Mail Robbery,” a group of armed men robbed a mail truck en route to Boston at about 8 p.m. on Tuesday, August 14, 1962. At the time, the theft of $1.5 million was the largest cash robbery in U.S. history, a record that later Mob-related heists would break. The mail truck was carrying cash deposits from Cape Cod banks to the Federal Reserve Bank in Boston. The robbers wore police uniforms to detain the mail truck and detour other traffic.

Early in the investigation, postal inspectors and law enforcement looked at John “Red” Kelley and George “Billy Aggie” Agisotelis as prime suspects. In early August 1967, with the five-year statute of limitations approaching, they indicted Kelley, Aggie, Thomas Richards and Patricia Diaferio. Richards disappeared before the trial. Aggie cooperated with authorities, but he also mysteriously went missing — Mob hitman Maurice “Pro” Lerner later claimed that he killed him. Kelley and Diaferio were both acquitted. No one was ever convicted, and some estimated the investigation cost as much, if not more than, the robbery itself.

Kelley was not a made man, but he operated within a criminal network that included armed robbers, mobsters and hitmen. He committed a string of robberies alongside other Mob affiliates and associates, including Boston mobsters Phil Cresta, Vincent Teresa and Carmello Merlino. While cooperating as a government witness, he admitted to being a hitman for hire for New England Mob boss Raymond Patriarca.

In Teresa’s book, My Life in the Mafia, he details how Kelley and associates planned and orchestrated the Plymouth Mail Robbery. In Teresa’s account, Aggie and Kelley led a group of bank robbers and holdup men to plan the robbery. For weeks leading up to the heist, Billy Aggie followed the mail truck to learn the route and determine necessary precautions.

In The Mob and Me: Wiseguys and the Witness Protection Program, former U.S. Marshal John Partington, who served as Kelley’s handler, outlined how Kelley folded Boston Mob boss Jerry Anguilo into the operation. Kelley claimed Anguilo gave the crew $7,000 for fake police uniforms, masks and shotguns and helped the crew launder the stolen money. His involvement illustrates an important point about heists: The men who pull them off may not all be mobsters, but the Mob expects a cut no matter what.

4. Pierre Hotel heist, New York City

In the early morning hours of January 2, 1972, seven armed men walked into the lobby of New York’s storied Pierre Hotel. They took about two dozen people hostage and stole a reported $3 million worth of money, bearer bonds, jewelry and other valuables from the hotel’s safe deposit boxes in less than three hours. Considered the largest hotel heist in history, experts estimate they likely stole much more than that, but victims of the crime underreported their losses.

Sammy Nalo and Bobby Comfort were professional burglars with a lengthy rap sheet, including the theft of $1 million in cash and jewelry from actress Sophia Loren at the Sherry Netherland Hotel. They claimed to have robbed and burglarized hotels across New York City, including the Drake and the Carlyle. They set their sights on the Pierre next and went to work selecting a team. They connected with Lucchese crime family associate Christie “The Tic” Furnari, who gave Nalo and Comfort the family’s blessing. According to Daniel Simone’s book, The Pierre Hotel Heist, which he wrote with Nick “The Cat” Sacco, another man who worked the heist, Furnari pulled in skilled burglar and fellow Lucchese associates Bobby Germaine and Al Visconti. To round out the team, they recruited Turkish hitman Ali Ben, his brother-in-law Al Green (not the singer) and contract killer Donald “The Greek” Frankos.

Nalo and Comfort selected the Pierre because it had only two security guards on duty overnight. It also had some of the city’s wealthiest guests. They picked January 2 because the morning after New Year’s Day was typically quiet, and safe deposit boxes at the hotel were likely filled with fancy jewels worn the evening before.

The men pulled up to the Pierre in three cars. Nalo, Comfort and Sacco were in a limousine driven by Green. Green stayed outside as the getaway driver, while the others entered the hotel. The group wore tuxedos, fake wigs and moustaches to conceal their identities. After entering the lobby under the ruse of a reservation for Dr. Forster, one of Comfort’s aliases, the men took hostage the security guards, hotel staff and guests in the lobby, totaling at least 19 people. Nalo and Germaine got to work opening the safe deposit boxes.

During early reconnaissance, Comfort had an affair with the hotel’s assistant bookkeeper, who told him how the hotel logged the contents of the safe deposit boxes. Comfort made the concierge share those logs to target specific high-value boxes. The thieves had until the 7 a.m. shift change to finish the job, so time was of the essence.

The heist is remembered not only for being one of the largest hotel heists in history, but for the hitches the robbers encountered. When a Brazilian guest, Mr. de Montejo, called down for an elevator, the crew took three more hostages: Montejo, his new bride and mother-in-law. Upon arriving in the lobby, they were met with a surprise. One of the other hostages was Montejo’s mistress — yes, he had a mistress in the hotel while on his honeymoon – leading to an uproarious confrontation with the newlyweds.

Another surprise occurred when hotel resident Jordan Graff came to the front door. As Frankos led him in at gunpoint, he began to suffer a heart attack. Not wanting to add murder charges to their criminal activity, the men called the first doctor they found in the registry, but the vacationing physician was too inebriated to be of much use. Comfort made the decision to call 911. Nalo and Germaine temporarily halted their efforts in the safe room to hide the hostages there. When a group of three police officers and two paramedics arrived and took Graff to a hospital, they had no clue they’d been greeted by the culprits of a robbery in progress.

Once that was over, the robbery resumed. Shortly after 6 a.m., the group began to clean up. Before leaving, they put the hostages back in the safe room and asked them not to act as witnesses for the police. Then they slipped $20 tips to each of the detained hotel employees — except for the security guards, who Comfort allegedly said had cop mentalities.

The police investigation into the robbery faced several uphill battles. The hostages did not provide useful descriptions or information, and many of the victims denied they had high-value items in their safes. Stolen jewels were later traced to Detroit and Rochester, New York, but the crime is still technically unsolved. Nalo and Comfort served time for possessing stolen goods connected to the heist, but none of the robbers was convicted of the crime itself.

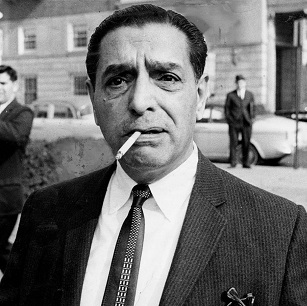

3. Bonded Vault heist, Providence, Rhode Island

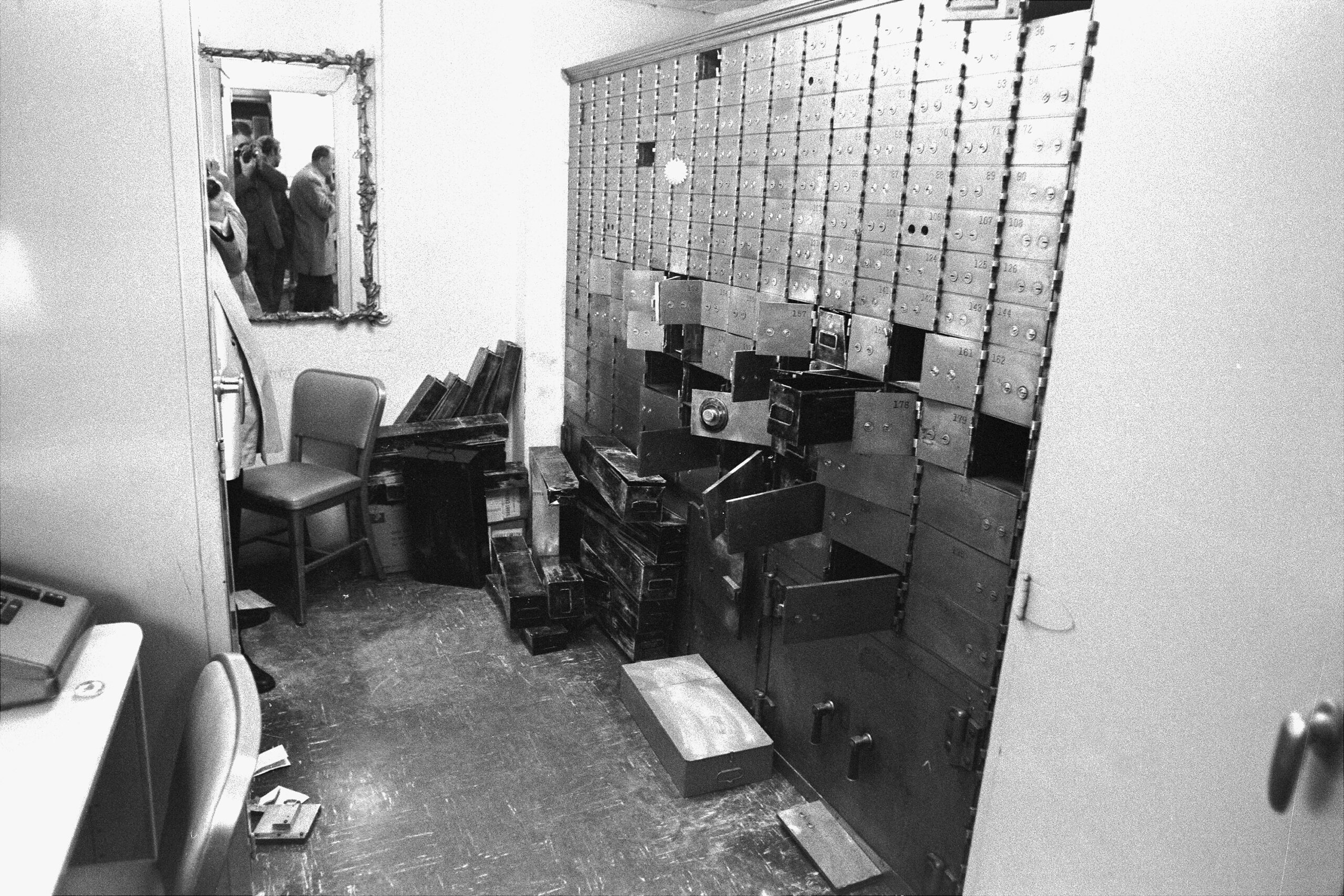

What happens when a Mob boss decides to rob his own criminal organization’s unofficial bank? The answer is found in the 1975 robbery known as the Bonded Vault heist. On the morning of August 14, 1975, about 8 a.m., eight men arrived at Hudson Fur Storage in Providence, Rhode Island. The men were not looking to rob Hudson Fur, but instead had their eye on what was called the Bonded Vault Company, a series of 146 large safe deposit boxes housed within the Hudson Fur building. It was commonly known that the Patriarca crime family and its associates stored cash and goods there.

One of the eight men, Robert “The Deuce” Dussault, had no problem corralling the storage facility’s five employees into an office with their heads covered by pillowcases. The storage facility had minimal security because of its association with the Patriarca family. Dussault then called six of his associates into the building and they began stealing the contents of the safe deposit boxes. To conceal their identities, the men called each other “Harry.”

First, they tried to drill open the safes. When that failed, they used a crowbar to pry off the solid steel doors. Ultimately, the seven “Harrys” left with millions of dollars — estimates range from $2 million to $30 million — in cash, gold and silver bullion, gems, guns and more.

The men then went to a hideout in East Providence where they each took $64,000 in cash and made plans to fence the rest of the valuables. Dussault took his cash share to Las Vegas, where he gambled it away and ran into trouble. In the meantime, one of the hostages from the heist cooperated with police, providing them with a description of two of the culprits, including Dussault. A Patriarca family associate also provided the names of the perpetrators.

Dussault decided to cooperate with law enforcement and testified along with another one of the robbers, Joe Danese. Ultimately, three of the six men who stood trial were convicted and three were acquitted.

As part of Dussault’s deal with the FBI, he revealed that Raymond Patriarca, then the Patriarca family’s leader, was the one behind the robbery. Dussault said most of the money went straight to Patriarca. Dussault alleged that Patriarca orchestrated the crime because he felt he was not getting his fair share from the family’s criminal activities while in prison for the murders of Rudolph “Rudy” Marfeo and Anthony Melei. The heist remains the largest in Rhode Island’s history.

2. Lufthansa heist, New York City

If you have seen the movie Goodfellas, you know a little something about the Lufthansa heist. At the time in 1978, it was the largest cash robbery on American soil and is considered the biggest heist in Mob history.

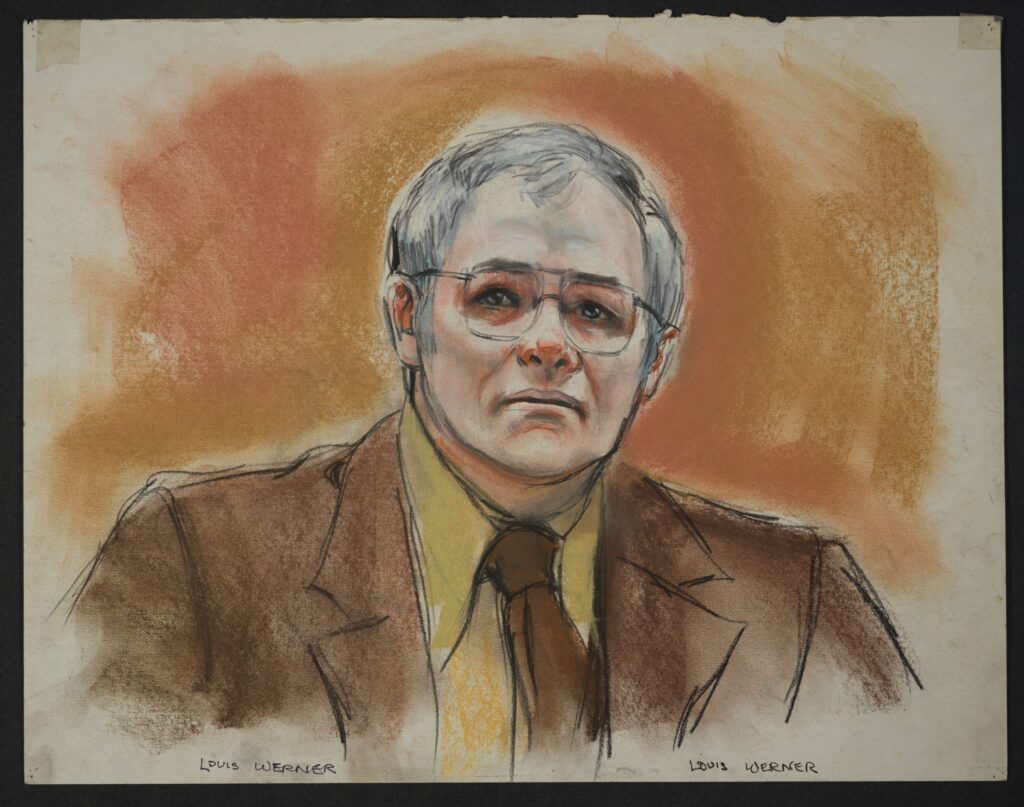

On December 11, 1978, at the Lufthansa cargo terminal at John F. Kennedy International Airport, six men made off with $5 million in cash and about $875,000 in jewelry. It was two Lufthansa employees, not the Mob, who first came up with the plan to rob the Lufthansa high-value room, which stored money and jewelry ready for transfer from German to American banks. Peter Gruenwald and Louis Werner realized their inside job needed criminal masterminds for a score of this magnitude. Werner, who owed $6,600 in gambling debts, shared the initial plan with bookmaker Martin Krugman, who recruited Lucchese associate Henry Hill.

Hill shared the plan with Jimmy “The Gent” Burke, who received permission from Lucchese capo Paul Vario to move forward with the heist. Werner shared a map with mobster Joe “Buddha” Manri and walked him through the security protocols at the Lufthansa cargo warehouse. On Saturday, December 9, Werner told the crew that a cash shipment of about $2 million had come in and would be in the high-value room until banks reopened on Monday morning.

On Monday, December 11, about 3 a.m., six men in ski masks pulled up to the Lufthansa warehouse. They cut the gate’s padlock with bolt cutters and walked in. They ushered the employees into the break room at gunpoint and forced the shift manager to disable the alarm and open the storage vault. At this point, the men realized that an unexpected second shipment had come in with more than $5 million in cash and jewelry for them to steal. By 4:21 a.m., the men had finished moving everything into their van and left.

Almost immediately, the FBI identified Burke and his crew as likely suspects in the crime. In February 1979, the police arrested Gruenwald, but there was a twist: Werner had boxed Gruenwald out of the plot. Even though Werner had paid Gruenwald a small share of the take, Gruenwald was not part of the final planning that resulted in the heist. With an ax to grind, he cooperated with law enforcement.

Authorities arrested Werner a few days later. He eventually would be sentenced to 15 years in prison. Werner was the only person connected to the heist to serve time for the crime, but not the only one to pay for it.

Exactly one week later, getaway driver Parnell Steven “Stacks” Edwards was shot to death. He had failed to properly dispose of the van used in the heist, and Burke blamed him for the FBI linking their crew to the crime. Krugman went missing and was presumed dead in January 1979. Joe Buddha was killed in May along with another man believed to have assisted with planning the heist. In total, 14 people connected to the heist were killed between December 1978 and May 1987 — 11 of them before the end of 1979.

In 2014, Bonanno family capo Vincent Asaro was indicted and arrested for alleged involvement in the heist but was acquitted of all charges.

As for Henry Hill, the inspiration for the main character in Goodfellas, he did not actually participate in the heist. He was arrested on narcotics charges in 1980 and became an informant, resulting in the revelation of his small role in the Lufthansa heist.

1. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist, Boston

On March 18, 1990, at 1:24 a.m., Richard Abath, a security guard at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston let two men in police uniforms into the museum. The two “officers” then duct-taped and handcuffed Abath and another guard. The men stole 13 works of art from the museum in 81 minutes — the largest art theft in history. Works by Vermeer, Rembrandt, Degas and Manet were among the stolen paintings. Before they left, the thieves also grabbed the videotapes from the security cameras that might have given a clue to their identity. Although Abath was never considered a suspect, the police scrutinized his behavior that night and investigated his finances.

In 1994, the museum received an anonymous letter offering to facilitate the return of the paintings in exchange for immunity and $2.6 million. The museum turned the letter over to the FBI, but the lead fizzled out.

In 2010, several news outlets reported that the FBI had submitted physical evidence from the scene for DNA testing. Then in 2017, the Boston Globe reported concerning news that some of the evidence, specifically the duct tape and handcuffs used to restrain the two guards, had gone missing more than a decade earlier.

One early — and lingering — theory placed former Winter Hill Gang boss James “Whitey” Bulger at the head of the heist. In this theory, Bulger planned the heist to funnel money to the Irish Republican Army, known for using valuable art to pay for guns. No evidence supports this theory, and Bulger said nothing about the heist when he was arrested in 2011, 16 years after he went into hiding.

In 1991, Bulger’s FBI handler, John Connolly, allegedly asked him about the heist, and according to Connolly, Bulger had an interesting answer. He did not know who had committed the heist but was just as interested as the FBI, because he believed the criminals responsible owed him tribute for committing the heist on his turf.

The FBI has allegedly investigated a number of people associated with the Boston Mafia in relation to the heist. In 2010, investigators searched the Maine home of Boston Mafia associate Robert Guarente, whom they believed had some of the artwork in his possession at the time of his death in 2004. FBI investigators believe Guarente acquired the stolen works from thieves George Reissfelder and Leonard DiMuzio, who both died in 1991. During the search, the FBI found nothing, but Guarente’s wife claimed he gave two stolen paintings to Connecticut mobster Robert Gentile, which he denied. In 2012, investigators searched Gentile’s home and found a handwritten list of the stolen paintings with their estimated worth.

Another Mob-connected theory involves Bobby Donati, whose body was found beaten, stabbed and stuffed into the trunk of his Cadillac in September 1991. Shortly after the heist, he allegedly visited Boston Mafia capo Vinnie “The Animal” Ferrara in prison and confessed to stealing the artwork as a bargaining chip to trade for Ferrara’s release from prison. According to former Boston jeweler Paul Calantropo, Donati also visited him in the spring of 1990. Calantropo said Donati showed him an eagle-shaped finial — one that looked identical to the one stolen from the Gardner Museum.

Today the case remains unsolved, although ties to organized crime have been suggested ever since the crime was committed. None of the art was reclaimed, and the museum continues to offer a $10 million reward for the safe recovery of the stolen works.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org