News site releases pages from huge FBI file on notorious New England Mob boss

Documents include report on Raymond Patriarca’s secret interests in Dunes Hotel in Las Vegas

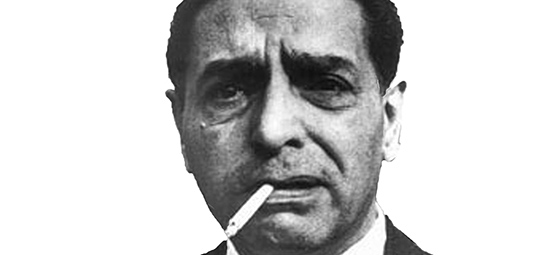

Raymond Patriarca, leader of a major New England crime family from the 1940s to the mid-1980s, seemed to live the life of a classic twentieth century American mobster.

A convicted robber and pimp in his early twenties, during the Prohibition Era, Patriarca developed a talent for cunning, intimidation, bribery, and disciplined secrecy to keep his interstate criminal enterprises flourishing. Things were going well through the 1950s until the FBI planted listening devices in his Providence, Rhode Island, office in the early 1960s that revealed his illicit activities.

Patriarca’s world slowly crumbled. He was sentenced in 1968 to five years in federal prison for conspiring to murder rival gambler William “Willie” Marfeo, who was shot to death in a phone booth in 1966. He was found guilty in 1970 in the conspiracy to hit Marfeo’s brother, Rudoph, and Anthony Melei, who were gunned down in a grocery store in Providence in 1968.

In 1980, police arrested him as an accessory in the 1968 murder of a man whose skeletal remains were found in 1970 with three bullet holes in his head. He also faced federal racketeering charges in 1981. But judges in both cases ruled he was too ill to stand trial. He died from a heart attack suffered while in bed with his mistress in 1984.

Patriarca’s disreputable legacy is being resurrected, with many new details, thanks to the GoLocal.com news website in Providence, which obtained almost 10,000 pages of partially redacted documents from the FBI through the Freedom of Information Act. The news group started scanning pages and on August 3 posted the first set of forty-two digitized copies in what it calls the “Patriarca Project.” The website plans to release other documents as they are scanned in the coming weeks.

The FBI’s file on Patriarca starts in 1953 with a one-page memo from the agency’s special agent in charge in Boston alerting FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover about a story in the Providence Bulletin newspaper concerning a prominent Rhode Island attorney, Thomas Paolino, who was recommended by a state Republican Party committee for a federal judgeship. Paolino had served as Patriarca’s lawyer in a legal dispute with the IRS over nonpayment of income taxes. Paolino insisted he no longer represented Patriarca. The FBI agent described Patriarca as the “reputed chief of the Rhode Island underworld” and “considered the number 1 hoodlum and racketeer in the entire New England area.” The memo ends by mentioning that another lawyer, not Paolino, had won the judicial appointment.

Subsequent FBI memos to Hoover relate to Patriarca’s infamous past, his extensive criminal activities, arrests, convictions, and purported efforts to use bribery to get out of legal jams. A report from the FBI in Boston dated May 19, 1954, named Patriarca as “the most outstanding gangster in Rhode Island” who was “identified as a member of an alleged National Syndicate.” (This memo is interesting in that Hoover in the 1950s publicly denied the existence of a national crime syndicate.)

The Boston office also pointed out that the U.S. Senate Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce (the Kefauver Committee) outed Patriarca as a major Mob figure years before. At a hearing by that committee in Washington, D.C., on July 7. 1950, Virgil Peterson, director of the Chicago Crime Commission, referred to Patriarca as “the king of the rackets in Providence, R.I., and is also tied up with members of the Frank Costello mob in New York.”

Patriarca was born on March 17, 1908, in Worcester, Massachusetts. He left school in Providence after the eighth grade, worked as a bellboy, mechanics helper, and rent collector. But he took a different turn. According to the May 19, 1954, memo, while in his twenties he “listed his occupation as professional gambler and racketeer and has been ever since.” Providence police referred to Raymond and his brother Francis as “drunk rollers and petty thieves during Prohibition when their father was said to be operating a speakeasy.”

Raymond soon graduated to more serious offenses. His long criminal record included breaking and entering, larceny, and armed robbery convictions from 1928 to 1944. His involvement in the prostitution racket resulted in his conviction in 1931, at age twenty-three, of violating the White Slave Traffic Act, or Mann Act, which got him a year and a day in federal prison. In 1938, back in Providence, he and accomplice Benjamin Tilley were caught holding stolen jewelry. A judge gave the ex-con Patriarca up to five years in Massachusetts State Prison on robbery, assault, and burglary charges. The FBI memo mentioned there were allegations Patriarca offered $12,000 to a witness to keep quiet. After only four months in state prison, Patriarca was paroled by Massachusetts Governor Charles Hurley after “a certain girl” delivered an illicit payment of $38,000 to Daniel Coakley, an aide to Hurley. (Coakley was subsequently impeached in 1940 for obtaining Patriarca’s release.)

The FBI in 1954 did not consider Patriarca a “violent” gangster. But agents reported that he “reaps a major cut from robberies and thefts in Rhode Island and other states” and is “owner and banker of many gambling establishments in Rhode Island.” Investigations indicated he operated a “shakedown racket in the Federal Hill section of Providence” and had a group of young men asking merchants for “protection money.” Those who refused to pay got their windows smashed.

The IRS, which said Patriarca owed more than $86,000 in back taxes from 1945 to 1951, maintained liens on property he owned until he agreed to settle, for $19,000, in 1955.

A leader in the local vending machine business, Patriarca at one point hired a henchman to pressure business owners to remove competitors’ coin-operated jukeboxes and replace them with Patriarca’s. According to the FBI, “he had no trouble getting his jukeboxes in because people are afraid to refuse” and did not want to risk the wrath of the “strong-arm man” Patriarca sent to their businesses.

By 1955, regarded as a “Top Hoodlum” by the FBI, an agency informant reported that Patriarca owned a “one-quarter interest in a million-dollar gambling house being built in Las Vegas, Nevada.” Although unknown at the time, that property was the Dunes Hotel, which was to open on May 23, 1955. Another informant reported on March 31 of hearing that Patriarca “in association with John Berborian, a well-known Providence gambler, and about ten other unidentified individuals, has purchased shares of stock or invested money in a gambling establishment” in Las Vegas and the “reported owner and moving force” of the casino was Joseph Sullivan, a member of a New Bedford, Massachusetts, family and widely known in illegal gambling circles in the Pawtucket-Providence area.” The FBI in Boston passed the information on to the agency’s office in Salt Lake City, which then held jurisdiction over Las Vegas.

Also that year, an informant maintained that Patriarca “has control of most of the New England area and receives a cut from all gambling activities.” Boston police questioned Patriarca about the murder of a café owner, William Rolfe, found dead on February 23, 1955. Rolfe was holding a penny in his hand, which the FBI said was “believed to be the underworld symbol for a ‘welcher.’” Patriarca, however, offered nothing of substance to investigators.

In 1956, when Patriarca entered the cigarette vending business, the FBI reported that he was associating with Louis “The Fox” Taglianetti (a New England Mafia soldier who would be murdered in 1970) and continued to enjoy proceeds from gambling in Rhode Island, Boston, and elsewhere in Massachusetts. He also had a piece of a company run by his brother-in-law that manufactured sweaters and employed mostly “salesmen who are connected with the hoodlum element” who went around town selling the clothing for cheap as stolen “hot merchandise” when they were actually legitimate.

The following year, an article in the Providence Bulletin claimed Patriarca was the person of “most powerful influence” alluded to in a 600-page report by the Massachusetts Crime Commission provided to state lawmakers about an estimated $2 billion illegal gambling network in Massachusetts. Also, according to the newspaper, Patriarca’s entry into cigarette vending with his firm the National Cigarette Service in 1956 displaced machines owned by other companies in fifty-five locations in Rhode Island, even though those companies had placement contracts. A judge issued a restraining order and injunction against Patriarca, at the request of a competitor, to prevent him from “bumping” machines from public spaces.

For some time in the mid-1950s, Patriarca effectively shut down leaks about his activities. A number of FBI memos during this period showed that people in Patriarca’s sphere of influence kept their stories straight. One phrase used repeatedly by agents included: “People are intensely loyal to him and in fear of him, and it is virtually impossible to obtain witness testimony of his activities.” Interviewees told agents over and over that Patriarca had “had a heart attack and was taking it easy.” A former commander of the Providence Police Department’s vice squad reported he “could not find anything” about Patriarca’s involvement in illegal gambling. Other local and state police officers told agents they “could not find anything” on him either. A longtime friend of Patriarca, Henry Tameleo (later convicted with Patriarca in the Marfeo murder), in an interview with agents described his friend as a “legitimate businessman” who “does not need to engage in illegal activities and has nothing to do with gambling or gambling activities.”

But Patriarca would start losing his grip thanks to intelligence information gathered in the 1960s with bugging of his Providence office and leads from informants. Damning testimony from hit man Joseph “The Animal” Barboza in the Marfeo murder case in 1968 led to Patriarca’s conviction and five-year sentence for conspiracy, and the beginning of his final downfall.

There is more to come from the “Patriarca Project” as further releases from his FBI file are posted by GoLocal.com in Providence.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org