The Commission trial lifted the lid on the New York Mafia

Thirty-five years ago, the FBI and federal prosecutors aimed to take down leaders of the Five Families

First of two parts.

In the annals of Mafia courtroom dramas, one case tends to stand above the rest, The United States v. Salerno, otherwise known as the Commission trial. This 1986 trial was full of theatrical highs and lows, and featured eight of the most prominent and feared New York mobsters of the time. They were:

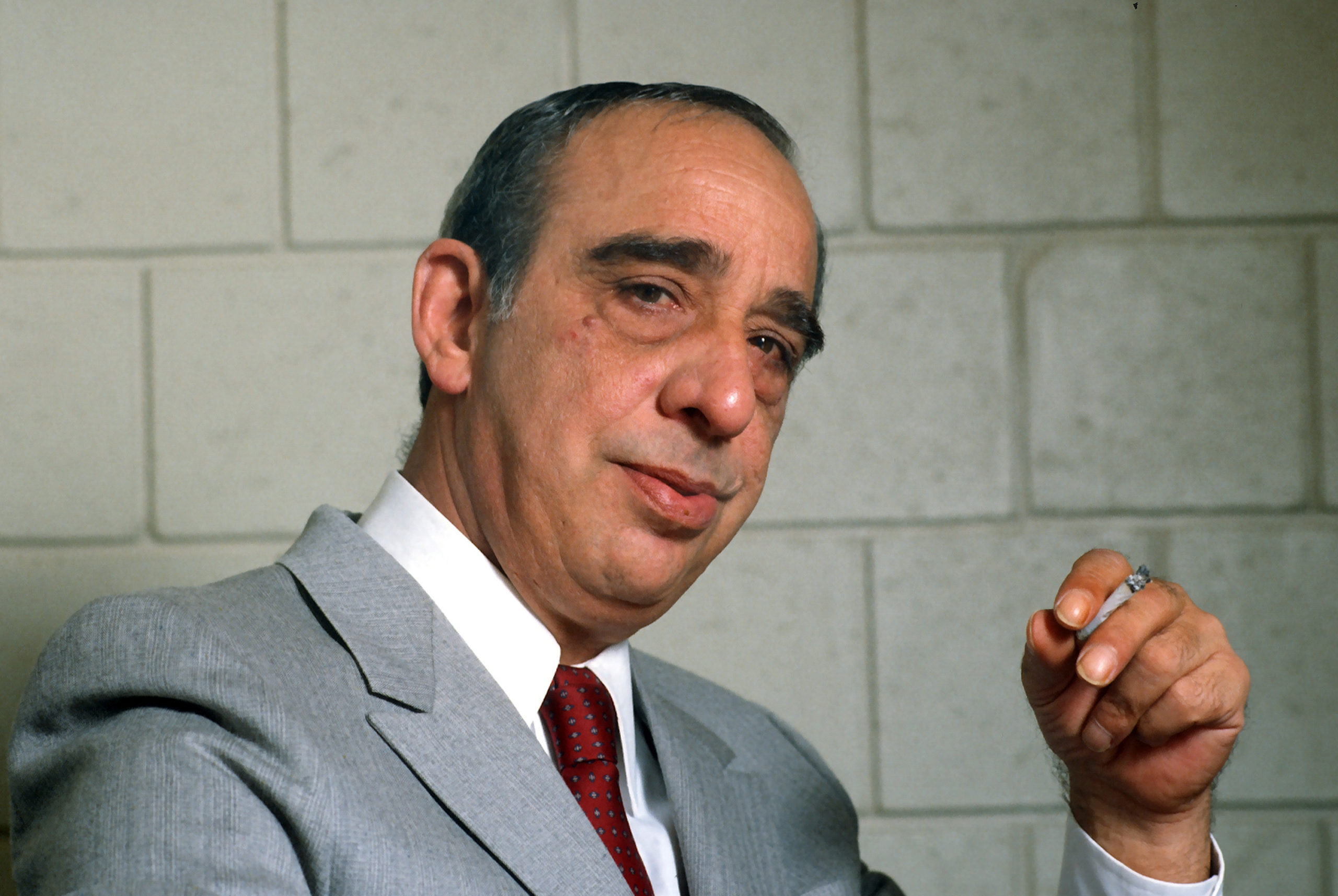

- Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, 75, boss of the Genovese crime family.

- Carmine “Junior” Persico, 53, boss of the Colombo crime family.

- Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo, 73, boss of the Lucchese crime family.

- Gennaro Langella (Jerry Lang), 47, underboss of the Colombo family.

- Salvatore “Tom Mix” Santoro, 72, underboss of the Lucchese family.

- Christopher “Christie Tick” Furnari Sr., 62, consigliere of the Lucchese family.

- Ralph “Little Ralphie” Scopo, 57, a soldier in the Colombo family and a former union leader.

- Anthony “Bruno” Indelicato, 38, a soldier in the Bonanno crime family.

That lineup would be interesting enough on its own, but this case offered added flavor when Persico decided to act as his own attorney. Judge Richard Owen ordered attorney Frank Lopez to serve as Persico’s legal adviser during the trial. Lopez said of Persico, “He could explain the case better . . . in his own homespun style.” “Style” is something the Mafia don definitely added to the proceedings.

A little background

The FBI and U.S. attorneys for the Southern District of New York had an ambitious goal: to take down the American Mafia by prosecuting three of the top five New York crime bosses.

The trial got its nickname from the entity created by Charles “Lucky” Luciano in 1931 to oversee the Mafia’s national crime syndicate. The Commission was composed of the bosses of the five New York Mafia families, as well as representatives from other prominent crime families across the country.

Anthony “Bruno” Indelicato, alleged killer of the cigar-smoking Bonanno family boss Carmine Galante, was included among the defendants to reveal to the jury the true murderous nature of the Mafia. Graphic photos of Galante’s bloodied and bullet-riddled body would be shown in court.

The original 15-count indictments were revealed in February 1985. The indictments were the product of five years of investigations, 171 court-authorized wiretaps and strategically placed bugs, and the work of more than 200 federal agents. By the time the trial started 18 months later, the indictment count had grown to 25, including charges of extortion, labor racketeering, narcotics, gambling and murder. The core mantra behind these indictments was that the Mafia Commission used “threats, violence and murder.”

The original indictment contained nine defendants. By the time the trial started, two names had been added, but three names had to be removed – they were dead by natural causes or otherwise. The three men removed from the indictment were Paul “Big Paul” Castellano, Gambino family boss (murdered December 16, 1985); Aniello “Neil” Dellacroce, Gambino family underboss (died of cancer December 2, 1985); and Stephano “Stevie Beefs” Cannone, Bonanno family consigliere (died of natural causes September 1985).

Samuel Dawson, attorney for Salvatore Santoro, had choice words about the indictments: “The indictment includes the Chicago fire and the San Francisco earthquake. I intend to prove that Mr. Santoro did not play with matches, or have anything to do with the earthquake.”

At the bond hearing, Magistrate Michael Dollinger read the obligatory statement warning that if the defendants were to threaten any witnesses in the case, their bail would be forfeited. “Christie Tick” Furnari asked, “What witnesses?” His attorney quickly led him out.

Let the circus begin

The trial started on September 8, 1986, on the third floor of the Manhattan Federal Court. The trial was THE show to attend in New York, and spectators never left disappointed.

Before jury selection began, Salerno’s attorney, Anthony Cardinale, argued that his client clearly was unfit to stand trial. As “Fat Tony” repeatedly dabbed at his right eye with a white handkerchief, Cardinale explained that Salerno was suffering from the recent effects of surgery less than a week before. Judge Owen denied the request.

Persico claimed he was facing double jeopardy. Earlier that year he was convicted of being the Colombo family boss. That case was now in the hands of the federal appeals court. Persico contended this trial should be delayed until after the appeals court issued its ruling. Judge Owen denied his request.

Arguments were then raised that the trial needed to be delayed because the defendants could not receive a fair trial because of all the pretrial publicity. Judge Owen denied the request as well.

What is the Mafia?

Before the jury could be selected, Persico had some “directives” for Judge Owen. First, he wanted to make it absolutely clear to the judge – and to the jury – that in no way can the Mafia be presented as or construed to be a criminal entity. Obviously, according to Persico, it was the government spinning this mistruth.

Persico went further when he attempted to guide Judge Owen on how to question prospective jurors. He explained, “Not too many of these jurors have a lot of education. I don’t believe you should use this terminology questioning the jury. You should use more lay language. They don’t understand this kind of language. I should put it in less – plainer terms.”

Judge Owen countered, “I’m accustomed to asking people questions in language that they can understand and answer.”

Jury selection started. Prospective jurors were given a quiz to determine if they knew, or had heard, of any of about 200 past and present Mafia figures or alleged mobsters whose names may come up during the trial. The list included Al Capone, Vito Genovese and Lucky Luciano. The quiz was given, and the answers were provided.

The jury was selected: seven women and five men.

Opening arguments

Opening arguments began on September 18, 1986.

The prosecution was intent on showing that the Commission was a criminal enterprise, and that each of the defendants was a member of the Commission, or of an entity directly under its control. Also, each of the eight men being tried had committed at least two – if not more – acts of racketeering to benefit the Commission and its goals. The racketeering fell into three categories:

1. The Commission directed bid-rigging (including extortion) in the New York concrete industry.

2. The Commission organized Staten Island loansharking territories.

3. The Commission ordered the murder of Bonanno family boss Carmine Galante, along with two of his associates.

U.S. Attorney Michael Chertoff described the Commission: “It’s kind of like a board of directors of a big criminal company.” The evidence he would present included surveillance photographs, videotapes and audio recordings. Among the witnesses were some high-ranking Mafia figures, as well as an undercover FBI agent named Joseph Pistone – known to the Bonanno family as “Donnie Brasco.”

“It’s not romantic, not like TV, the movies or books,” Chertoff told the jury. “You’ll see them fighting, back-stabbing each other. The Commission was dominated by a single principle – greed.”

Yes, there is a Mafia

The defense attorneys went into preemptive attack mode, knowing that one of the prosecution’s goals was to emphasize how the defendants were all going to deny the Mafia’s existence. In his opening statement, defense attorney Samuel Dawson said, “This case is not about whether an organization is in existence, known as the Mafia or La Cosa Nostra. There is – right here in New York City.” But he said there was no evidence the defendants were guilty of the racketeering charges.

Dawson turned to the jury and asked them this simple question: “Can you accept that just because a person is a member of the Mafia, that it doesn’t mean he committed the crimes charged in this case?” He paused before he reminded them that, “You each assured us that you would accept and abide by that basic point.”

“Yes, there is a Commission,” Dawson stated in a matter-of-fact way. But, he said, the Commission’s only function was to approve of new members, and to resolve conflicts between groups. The Commission was not about extorting money from the construction industry, it was only setting prices to avoid competition. “This is a bid-rigging case. An antitrust case. The government has reached for more than what the evidence shows.”

The admission to the Commission’s existence was one of the first times in history when a defense attorney disclosed this about the American Mafia.

It was attorney John Jacobs’ turn. In a unique opening, he said that, yes, his client (Ralph Scopo) did accept some labor payoffs. But, he explained, Scopo didn’t accept the payoffs for the Mafia.

Now it was Persico’s turn to make his opening statements. With his gold-rimmed glasses and black pin-striped suit, he spoke softly to the jurors in a friendly, conversational way. His strategy was to win the jury over with charm, self-abasement and empathy. The jury couldn’t possibly convict someone they liked, right?

“Guess by now you all know my name is Carmine Persico, and I’m not a lawyer. I’m a defendant,” he said with his strong Brooklyn accent. He confessed to being a “little nervous” while he flipped through his notes on a yellow legal pad. He added, “Don’t let them (the prosecutors) blind you with all the labels. Keep your eye on the issues.”

Persico then said, while he smiled and raised his hands, “Mr. Chertoff says the Mafia … is all about making money. The government wants you to believe the money went up to the Commission and the orders came down. I’d like to know where that money went. You won’t see it coming to me. They can’t try me on gossip, or rumors.”

Persico lowered his voice and spoke with an ominous tone. “Be wary of prosecution witnesses.” He speculated that these witnesses would include murderers and drug dealers. And how were these “stellar” witnesses being paid? They were being paid, he said, with “your money and my freedom.” “They are powerful,” he emphasized as he pointed to the prosecution team. “Not me. … I’m sure after you hear all the evidence, you will acquit me.”

From their own mouths

On the first full day of the trial, the jurors were advised they would be listening to tape recordings of some of the defendants and their associates. The first set of tapes was a conversation between “Tony Ducks” Corallo and an associate, Salvatore Avellino. A bug had been hidden in Avellino’s Jaguar.

Before the tapes were played, the prosecution presented a New York state investigator, Richard Tennien, who testified that he took part in the electronic surveillance. Persico decided Tennien was the perfect person on which to flex his cross-examination muscles.

“How long did you work on this investigation?” Persico asked in a friendly manner.

“Approximately a year,” Tennien answered.

“Did you ever hear anyone in the car describe themselves as members of organized crime?” Persico asked.

“In that terminology, no,” Tennien replied.

Contending that organized crime was a term invented by the government, Persico continued, “Policemen talk that way?”

“Yes,” Tennien answered, adding, “It’s just another term to describe the Mafia, La Cosa Nostra.”

Persico was determined to make a point. He asked Tennien if he himself used the term organized crime “just to make it sound more criminal?”

“No,” Tennien answered. Persico, knowing he didn’t accomplish what he had set out to do, ended his cross-examination.

The jury was instructed to put on large, black headphones, open the transcripts in front of them, and follow along. Transcripts were needed as some of the recorded conversations, at times, were difficult to understand.

The defense instantly disputed the audibility of some of the tapes, and questioned the accuracy of the transcripts. They had to plant a seed of doubt. They knew they only had to turn one of the jurors to their side to win the case.

The tape started to play. “Tony Ducks” and Avellino were discussing the problems with family members dealing in narcotics. Dealing was not approved by the Commission. How should these dealers being handled, Avellino asked. “Tony Ducks” replied, “We should kill them.”

Fat Tony identified

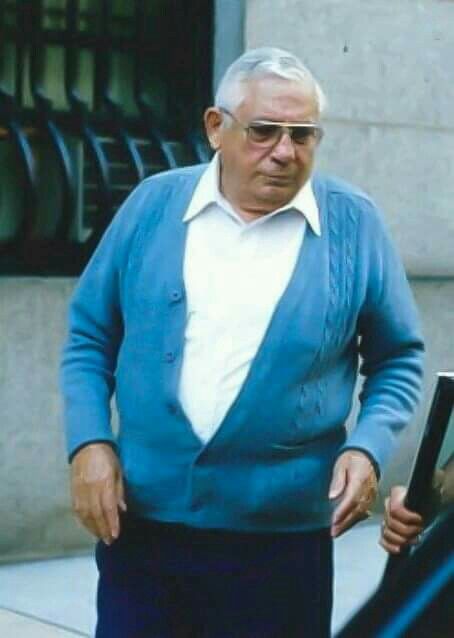

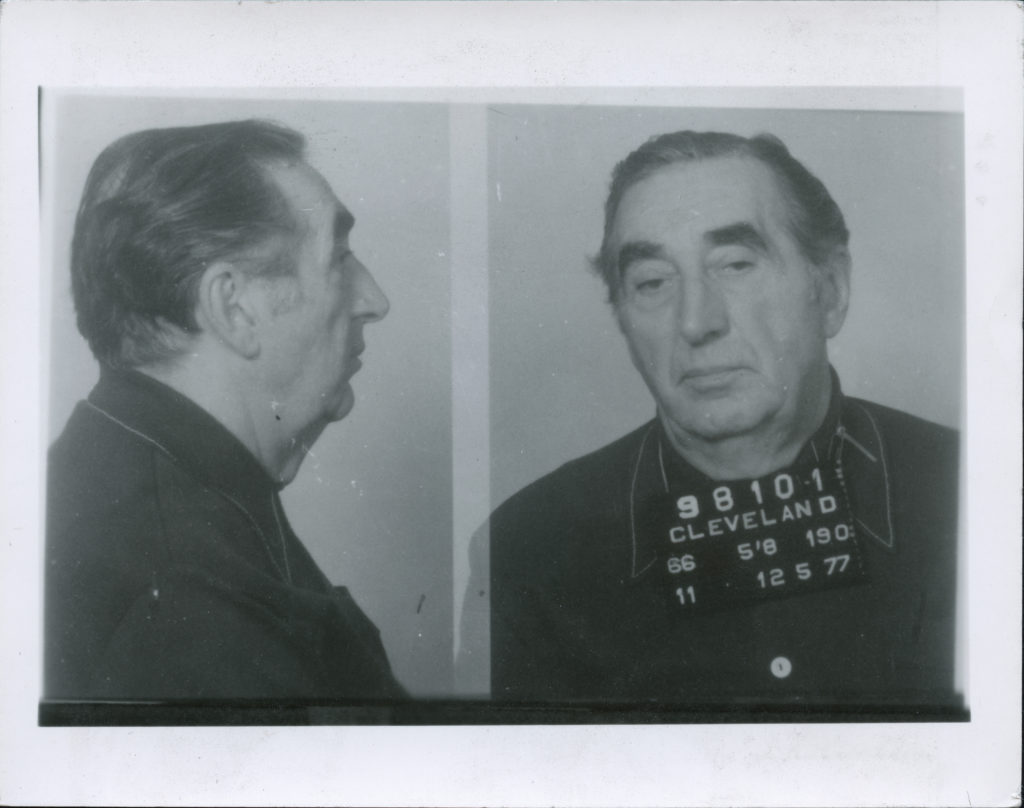

The oath of “omerta” – the Mafia’s code of silence – was thrown out the window when a former Cleveland Mafia underboss took the stand. Angelo Lonardo, (son of Joseph “Big Joe” Lonardo, former Cleveland family boss), was one of the highest-ranking Mafia figures to ever become a government witness. The 75-year-old Lonardo provided insights into how the Commission worked with the different family bosses outside of New York City. Lonardo’s family communicated to the Commission through Tony Salerno. He testified that Salerno was not only part of the Commission, but the boss of the Genovese crime family.

Attorney Chertoff asked Lonardo to look around the courtroom, and please tell him and the jury if he recognized any Mafia bosses that he had personally met. Stepping down from the witness stand, the older man looked the room around before his eyes became fixed on an individual sitting at the defense table.

“Yes, I do – Tony Salerno,” Lonardo said, pointing his hand toward Salerno. Soft murmurs raced across the courtroom as all eyes darted from Lonardo to Salerno. Salerno’s only response was a slight lift of the chin and a narrowing of his piercing eyes.

“People used to refer to him as Fat Tony,” Lonardo continued. “He’s a little thinner.”

Lonardo explained that the bosses of the five New York families controlled the entire national Mafia through the Commission.” He identified the five New York families as Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese, Colombo and Bonanno.

“If there’s a dispute about anything,” he explained, “they get together and iron it out.” Lonardo continued, “They make all the rules and regulations – what you can do, what you can’t do.”

And how did the feds get Lonardo to willingly testify about his former Mafia brethren? He was offered a deal. Lonardo had previously been convicted of drug charges. His sentence was “life without parole, plus 103 years.” By “cooperating,” his sentence was reduced, and he was being considered for parole.

Time to garden

Week after week, as the trial marched forward, the American public wanted more inside information and more shocking details. This was the face of America’s feared Mafia hierarchy? Agreed, they were a little rough around the edges, but that didn’t mean they were guilty. A lot of people were rough around the edges. And three of the defendants were in their 70s. Were they really running the Mafia at that age? Then again, President Ronald Reagan was 75 years old, and he was running the whole country.

Doubt had to be “planted,” and Carmine Persico was determined to be that “gardener.”

Marcy Knight is a freelance writer based in Florida.

Read Part Two: The 10-week-long Commission trial played to full courtrooms

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org