Citing coronavirus risks, Italy releases four imprisoned Mob bosses

Another 70 aging bosses may be sent to house arrest because of health issues in nation’s prisons

During the coronavirus pandemic, the world’s prisons are among the hotspots for the disease. Inmates living in close proximity create an ideal environment for the contagion to spread. That has prompted officials in multiple countries to grant early release to hundreds of thousands of criminals, including organized crime bosses.

In the United States, those permitted to walk from county jails or state and federal prisons to home confinement, as least temporarily, include former Donald Trump lawyer Michael Cohen and Michael Avenatti, ex-attorney for one-time porn actress Stormy Daniels.

But in Italy, with its extraordinary number of Mob-connected inmates, the impact of COVID-19 — and perhaps a surplus of government compassion — has led to the recent release from prison of four notorious crime bosses.

As many as 70 other Italian bosses may prove eligible for conversion to home confinement based on their advanced age and recognized health problems.

Despite the unsavory reputations and criminal acts committed by these men, a law passed by the Italian government aimed at releasing prisoners older than 70 and in poor physical shape to protect them from the virus.

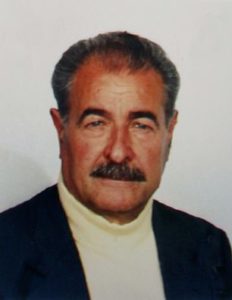

One prominent boss already permitted to walk from prison, into house arrest, is Francesco Bonura of Palermo, who, at 78, served eight years of the 23-year sentence imposed on him for racketeering and cocaine trafficking in a case involving other top Sicilian bosses in 2012.

Decades earlier, Bonura got off on a technicality in a case in which authorities charged him with five murders. Still considered the head of the Uditore, one of more than 100 crime families in Sicily, Bonura was imprisoned in the wake of major anti-Mafia legal reforms since the 1990s that imposed harsher prison sentences, the seizure of criminal assets and greater protections and incentives for witnesses to testify in organized crime trials.

Italian judges have also set free three other infamous crime leaders. Two are members of the powerful ’Ndrangheta of the southern province of Calabria: 65-year-old Vincenzino Iannazzo, and Rocco Santo Filippone, 72. The fourth is Pasquale Zagaria, 60, of the Casalesi clan with the Camorra family based in Naples.

Lawyers for Iannozzo, serving 14 years in a federal prison in Umbria, convinced a judge to release him to house confinement, even though he is younger than 70, claiming he was at risk to the virus based on his gender, age and various pathologies such as “immune deficiency from chronic anti-rejection therapy for transplantation.”

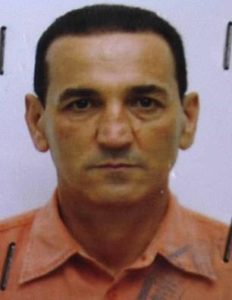

Filippone offered a more straightforward plea for release to house arrest: He’s older than 70 and suffers from heart disease. Of the two ’Ndrangheta bosses, Filippone’s exit from prison is more troubling.

A court convicted him and another boss, Giuseppe Graviano, in the 1993-1994 attacks on Italian police patrols in Reggio Calabria that killed two officers and wounded two others. Filippone and Graviano acted on orders from their boss, Salvatore “Toto” Riina, who in the 1990s sought to intimidate the Italian government to halt or soften anti-Mafia measures through terrorism-style murders of public officials. Riina orchestrated the assassinations of prosecutors Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, both killed in bombings in 1992, which shocked the country and triggered the passage of anti-Mafia legislation and new crackdowns on crime families. While serving a life sentence, Riina died in prison in 2017 at age 87.

The Italian news media refers to Zagaria, less of a boss with the Camorra than his brother Don Michele Zagaria, as the “economic mind” of the crime family’s Casalesi subgroup. He has been in prison since 2007, when a court sentenced him to 27 years. But his declining health has placed him at risk for the coronavirus, and doctors claim he needs cancer treatments that cannot be adequately provided in prison.

Concerns about the coronavirus have reached such a height in Italy, where more people have died from the malady than any country except the United States, that the society seems willing to let loose crime bosses, even if that means they may resume their illegal deeds remotely from their homes.

Some Italian officials have complained publicly about the judicial reasoning behind the releases. Matteo Salvini, leader of the Italian far-right party, the League, posted his reaction on Facebook: “That is crazy. It’s a lack of respect for people, magistrates, journalists, policemen and victims of the Mafia.”

Leo Beneduci, secretary general of the largest prison police officers’ union in Italy, in an interview with the British newspaper The Guardian, pointed out just how pervasive organized crime is in his country, in and out of its prisons.

“It is a very alarming situation,” Beneduci said. “In Italy there are approximately 12,000 members of criminal organizations in prison. Members of the penitentiary police have begun reporting detainees who embrace each other with the alleged goal of increasing the possibility of contracting the virus and getting released from prison.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org