Netflix’s ‘Fear City’ reveals how FBI, prosecutors built the Mafia Commission case

Documentary series provides fewer insights into the underworld impact of the trial of New York’s Five Families

The Netflix documentary series Fear City: New York vs. the Mafia tells the story of the investigation and prosecution of what came to be known as the Commission case, the bold effort by the Justice Department and the FBI to take down the five organized crime bosses in New York in the 1980s. It was called the Commission case because the five dons representing the “Five Families” of the New York Mafia held seats on the Commission, a sort-of board of directors of organized crime, governing Mafia activities in New York and across the country.

Charles “Lucky” Luciano formed the first Commission in 1931. He did so after leading a violent campaign to eliminate “Mustache Petes” – old-fashioned Mafia bosses of limited vision – in favor of younger leaders capable of operating criminal enterprises in more modern and sophisticated ways. The Commission’s power and membership varied greatly over the decades but it continued to settle disputes and issue edicts well into the 1980s.

Fear City is well done. Its producers deserve a ton of credit for tracking down many of the key players in the Commission case and convincing them to open up on camera. But it is important to understand that the three-part series tells the story from a specific perspective. This is a documentary about the FBI agents and prosecutors from the U.S. Attorney’s Office who were involved in gathering evidence and building the case. A total of 16 agents, investigators and prosecutors were interviewed on camera. But the series offers little for those seeking insights into the New York Mob and the impact of the investigation at that time.

The filmmakers interviewed just two former mobsters to carry the load for that side of the story: Michael Franzese and John Alite, both of whom, incidentally, have spoken at The Mob Museum. Each contributes valuable color to the storytelling, especially in the first half of the series. Franzese and Alite highlight the fact that the Mafia in the 1970s – in the decade before the Commission case went to trial – was extremely powerful in New York.

“It was the golden era of the Mob,” Franzese says. “The FBI couldn’t keep up with us.” He adds later, “We prospered because we infiltrated every fabric of society.”

Alite has a similar recollection: “We were untouchable. Who was going to stop us? You felt like you had the power to do anything you wanted.”

Of course, the Commission case changed all that. Taking advantage of a little-used law up to that time, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, prosecutors were able to construct a case against the Mafia bosses even though they could not be directly linked to the murders, robberies, extortions and other crimes committed by their underlings. As FBI agent Jim Kossler says, RICO “would change everything.”

The strength of Fear City is in the interviews with FBI agents revealing how they gathered evidence. And the star among the agents is Joe Cantamessa, a special ops guy who relates a couple of fascinating anecdotes about planting bugs in mobsters’ houses. I won’t spoil the documentary by going into detail, but suffice to say that Cantamessa and others were very creative in how they went about their business – and they took considerable risks to get the job done. And as Cantamessa notes in describing one of his bug-planting adventures, “I’m making this up as I’m going along.”

Other agents were assigned the more tedious but no less important task of listening to recordings of the bugs and wiretaps. Amid the long silences and routine family dialogue, they found nuggets of evidentiary gold. The FBI had an incredible 25 bugs and wiretaps going at any one time in the 1980s, creating a daunting number of hours of audiotape to be reviewed.

One of the biggest revelations of the Commission investigation was the existence of “The Concrete Club,” which was shorthand for the Mafia’s almost-total control of commercial construction in New York City. “The Concrete Club has to be one of the most audacious schemes that the Mob has ever pulled off,” prosecutor John Savarese says in the third episode.

Another coup for investigators was their surveillance of a meeting of the Commission. Video shows the Mafia kingpins entering and leaving a business. “This is a Commission meeting unfolding right in front of our eyes,” agent Joe O’Brien says.

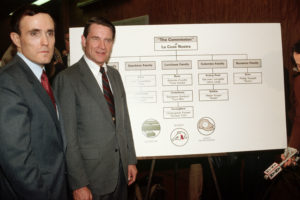

The 1985 arrests of the Mafia bosses and the subsequent 10-week trial were a media circus, with U.S. Attorney Rudy Giuliani as giddy ringmaster. Giuliani relied on a trio of young prosecutors, including future Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, to try the case, but he deserves credit for conceiving of and championing such a bold and risky endeavor.

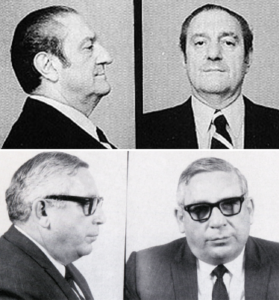

Ultimately, the jury found all eight mobsters tried in the case guilty, including three top bosses – Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, Antonio “Tony Ducks” Corallo and Carmine “Junior” Persico. Seven of the defendants received 100-year sentences, and one, Anthony “Bruno” Indelicato, got 40 years.

Sadly missing from the documentary is any reference to Persico representing himself during the Commission trial. As the New York Times reported at the time, Persico “provided some of the trial’s most memorable moments, using a sardonic, streetwise humor to address the jury and question witnesses.” Often referring to himself in the third person, Persico wondered why he did not appear on any of the FBI’s surveillance tapes. “Maybe he didn’t want to meet anybody anymore,” he said. “Maybe he had had enough. Maybe Carmine Persico was tired of going back and forth to jail.”

A few critics have found fault with Fear City. Q.V. Hough, writing for Screenrant.com, complains that “the backstory of the New York Mafia” is completely missing. The series, he says, “ignores 100 years of history.” I noticed this, too, but it’s clear that director Sam Hobkinson decided to limit the scope of his story to a particular snapshot of time and place. The backstory Hough seeks can be found in hundreds of books and dozens of cable television specials. It’s practically the raison d’etre of The Mob Museum. As a historian, my instinct would have been to include the wider historical context, but Hobkinson had a different vision.

Hough also says Fear City “rushes through the specifics” of the RICO law that served as the foundation for the Commission case. He is right. While the filmmakers landed an interview with RICO creator Robert Blakey (who also has spoken at the Museum), they spend too little time explaining the law and its advantages and pitfalls.

Writing for Vox.com, Alissa Wilkinson is particularly hard on Fear City, but she reveals her biases in the process. She is offended by the fact that Giuliani’s more recent issues as a lawyer and adviser to President Trump are not included in the documentary. But director Hobkinson clearly made a decision not to bring the stories of all the characters depicted in the documentary up to date. As mentioned before, he limited the scope of his storytelling, omitting most of what happened before and what happened after. Within this context, it would have been odd for him to add three minutes about Giuliani’s 21st century political activities.

Wilkinson makes a better case when she criticizes Fear City for doing so little on the interplay between the Mafia and Donald Trump in the 1970s and ’80s. Trump certainly was not the only New York developer victimized by the Mafia’s influence in construction, but he was the most prominent. While this is mentioned in the documentary, Wilkinson rightly asks, “How did Trump deal with the Mob? To what extent? Were his actions criminal?” Attempting to answer these questions could have helped illuminate exactly how the “Concrete Club” operated.

In the end, Fear City is a revealing case study in how FBI agents do their work. For those interested in the nuts and bolts of how law enforcement took down the Mob in the last three decades of the 20th century, this documentary is a revelation. But for those looking for new insights into the Mafia, or for a hit piece on Trump and Giuliani, Fear City will not satisfy.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org