Mobsters in the military

Despite extensive criminal histories, Monk Eastman and Moe Dalitz served their country admirably in war

Historically, the U.S. military has alternated in size between small standing armies in peacetime and vastly expanded forces during war. The two world wars produced periods with the largest numbers of men in military uniform in U.S. history. The U.S. military during World War I was more than 4.7 million, for a small period of involvement, just more than a year and a half. In World War II, the United States had more than 16 million men and women in military uniform.

With so much of the population in military service, it is perhaps inevitable that there would be mobsters in the ranks. Some became involved with organized crime after their military service, such as George Barone and Matthew “Matty the Horse” Ianiello, who served in the Navy and the Army respectively during World War II, and who both found their way into New York’s Genovese crime family. Others enlisted after or in the midst of long careers in organized crime. Edward “Monk” Eastman, a gang leader in New York who spent time in prison before he served in World War I, and Morris “Moe” Dalitz, a bootlegger and illegal casino operator before he served in World War II, are two of the most well-known examples.

Eastman ran with petty criminal gangs in New York in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He worked his way to the head of a local gang, which initially focused on small-scale larceny, and gained infamy as the Eastman Gang. The gang thrived in the violent New York underworld at the turn of the century, and expanded rapidly, at one point having roughly 1,200 thugs and thieves answerable to Eastman. The gang broadened beyond larceny into running brothels and dabbled a bit in dealing opium. The gang’s muscle also earned the attention of the political bosses of Tammany Hall, and they were put to work rigging elections and intimidating voters. In return, Eastman and his gang were paid and usually protected from police attention. An arrest would be quickly followed by Tammany Hall’s lawyers appearing at court. Where legal wrangling didn’t get results, bribes and threats often could.

Monk’s first known arrest and conviction, for larceny, earned him three months at Blackwell’s Island, in New York, in 1898. Four years later, with the increased attention the gang was getting, his arrests began to gain more attention in the news. Eventually, the multi-hour Battle of Rivington Street, a shootout with the rival Five Points Gang, sent an enormous shock through the public. Tammany Hall decided to let Monk face his next arrest without the assistance of its lawyers, and he was imprisoned for his role in a robbery and shootout with a pair of Pinkerton detectives. He was convicted and sentenced to a ten-year stint in Sing Sing prison. After serving five years, he was released, but found that his gang had split up and moved on. Without the structure of his gang, Monk’s criminal activities scaled down to larceny and opium, to which he became addicted. The opium trade earned him eight more months at Sing Sing, and an attempt to steal silver sent him to Clinton Correctional Facility at Dannemora for nearly three years. He was released in October 1917, six months after the United States had declared war on Germany. The U.S. was still building up the expeditionary force needed to actively enter the conflict.

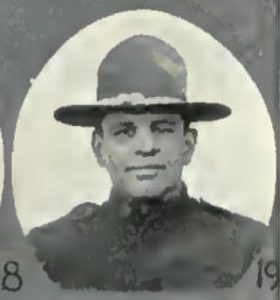

Monk enlisted, and entered service with the 106th Infantry Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division. His medical examination upon enlistment is the source of an oft-told anecdote, in which the doctors could barely believe the network of scars from blades, bludgeons and bullets that covered his body. He is reported to have answered a question about which wars he had been in with the quip, “Oh, just a lot of little private wars around New York.” American forces arrived in Europe in the summer of the following year, and Eastman saw active combat in some of the most decisive and hard-fought battles at the end of the war, including the Somme offensive and the breaking of the Hindenburg Line. While Monk had enlisted under an assumed identity, he stood out for his age and prowess, reportedly outrunning the younger men during training and impressing all with the force of his bayonet strikes on practice dummies.

His fellow enlistees discovered his true identity, and after that no more jibes about his age were made by the younger recruits. He seemed to take on a “tough older brother” role to his fellow soldiers. The men of the 27th trained at Camp Wadsworth, in South Carolina. They learned to build an entire trench network, watch it be shelled, rebuild it, go through gas drills and suffer the indignity of being judged “dead” by observers if they so much as showed their heads above the wall of the trench while not actively firing. Once they reached France, their training was taken further by British veterans of the brutal trench warfare. The 27th were the beneficiaries of years of experience the Europeans learned the hard way. Actual combat was far more grueling.

Monk Eastman was in his element. He had taken to the disciplined life of a soldier very well, and in the trenches he really began to shine. Out of necessity, troops were rotated in and out of the trenches, to give them a much-needed break from the muddy filth and constant artillery barrages. Monk requested to stay, when his company rotated out, to act as a stretcher bearer for the incoming unit. He frequently threw himself into no man’s land to rescue and retrieve fallen soldiers of his unit, including his squad sergeant. He gained notoriety for crawling up on machine gun nests at Vierstraat Ridge with a handful of grenades to stop them from shooting at his brothers-in-arms, incurring shrapnel wounds to his legs. He even insubordinately escaped from a hospital, where he had been confined after his leg injury. There it was discovered that he had been gassed and simply had not told anyone. Standard procedure was to keep gas victims under observation until their lungs either recovered or they died. Monk simply left in the confusion, so he could return to the front line with his unit, for the action at the Hindenburg Line. Eastman’s unit and commanders thought so highly of his service that they compiled a large volume of letters from his officers and fellow soldiers, requesting a pardon and reinstatement of his citizenship and rights. Monk’s exploits had gained so much interest in the newspapers that New York Governor Al Smith granted the petition from the 27th Infantry Division. Details of Monk’s military service were outlined in newspaper articles, the petitions submitted to the governor and military service records. In addition, many of the specifics are detailed in Neil Hanson’s book Monk Eastman: The Gangster Who Became a War Hero.

Sadly, Eastman’s exemplary combat service to his nation, and the high regard in which his fellow veterans held him, did not prevent him after the war from exploring the hot new criminal enterprise of the day: bootlegging. Eastman was just starting to feel out his entry into the opportunity that Prohibition provided when an argument with one of his partners resulted in his death on December 26, 1920. The partner, a Prohibition agent looking to make money on the other side of the law, pulled a gun and shot Eastman several times. Eastman’s recent fame and stature as a war veteran brought a great deal of interest from the press. Where they once eagerly reported on his arrests and trial, now the hunt for Monk’s killer made headlines. Jerry Bohan, the corrupt Prohibition agent who had gunned him down, was swiftly caught, and he confessed to the killing. Monk’s fellow veterans of the 27th ensured that their fallen comrade received the hero’s funeral procession they believed he deserved. In an ironic touch, the funeral procession included a police escort.

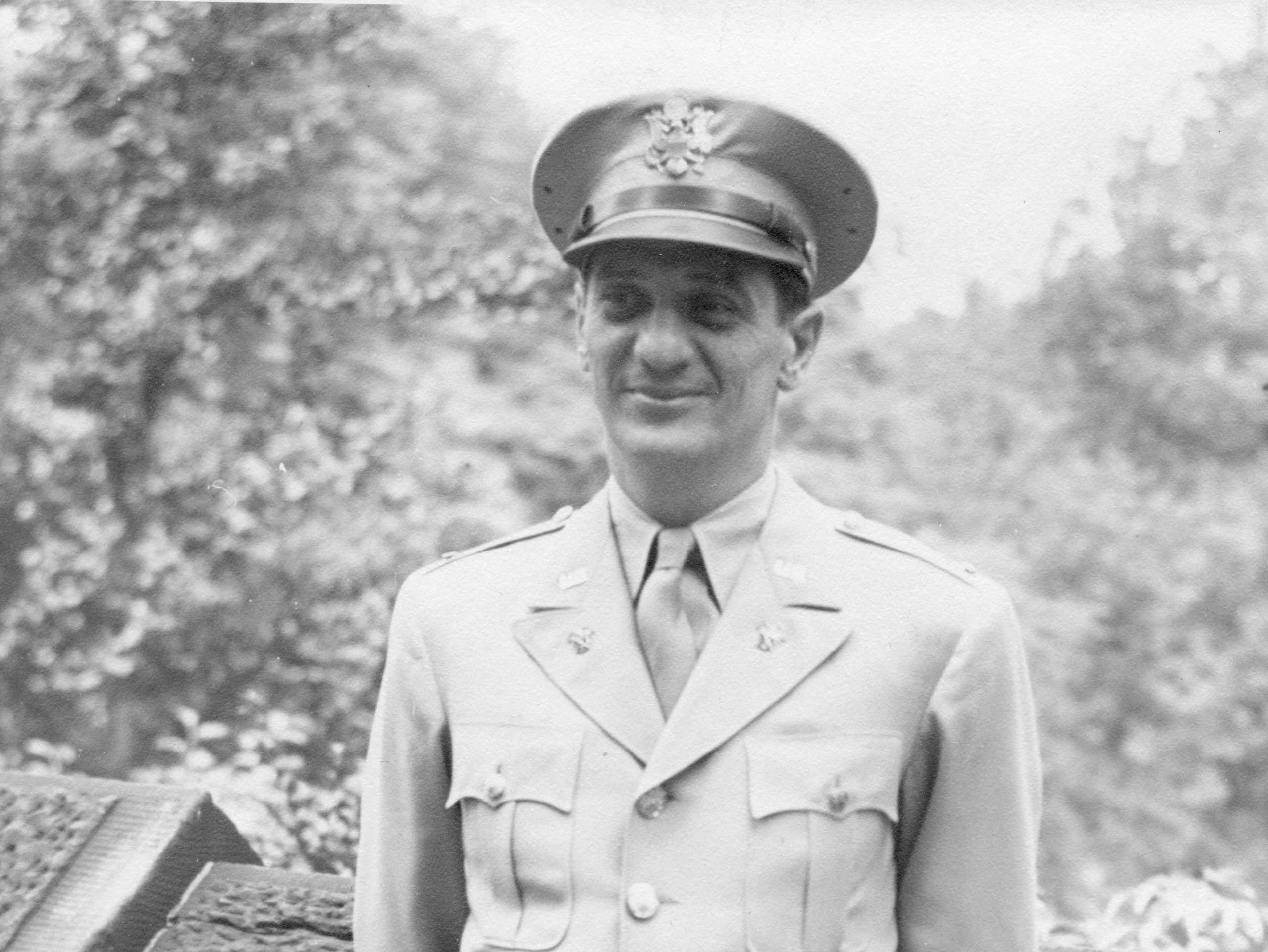

Morris “Moe” Dalitz entered into bootlegging right at the beginning of Prohibition, in 1919. Dalitz’s family owned a laundry business, and the laundry trucks that were used for deliveries proved an excellent method of smuggling booze. Dalitz prospered in bootlegging, but always kept his legitimate businesses in mind, pouring his profits from bootlegging into the laundry business, which in turn provided the means to expand bootlegging. Dalitz formed relationships with the Galveston syndicate, which brought in alcohol from Mexico and Canada, and made contacts with other organized crime figures, including Meyer Lansky and Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel. Around 1930, Dalitz moved from Detroit to Cleveland, expanding his presence and laying the foundation for what would be his next illicit business. The end of Prohibition meant the end of bootlegging, and Dalitz believed that gambling would be the next high-return opportunity he could exploit. He operated a number of illegal casinos, such as the Beverly Hills Supper Club in Covington, Kentucky, and the Pettibone Club in Ohio. These gambling businesses, while known of by law enforcement, were generally tolerated. His involvement in gambling continued even while he enlisted in the Army in June 1942, six months after Pearl Harbor. As Dalitz explained in an oral history in the 1970s, he “missed the First World War by a year.” “I was too young. I had an older brother who did make the first one. His name was Louis Dalitz,” but in the emotionally charged aftermath of the attack by Imperial Japan, “with all the excitement of Pearl Harbor, I, like many other people, walked into a recruiting office.” Dalitz requested to go overseas to fight.

Unlike Monk Eastman, Dalitz did not serve in a combat role. He was not even sent outside the United States. Instead, the Army realized Dalitz had much-needed experience that was valuable to the Quartermasters Corps. With his lifelong knowledge of the laundry business, he was invaluable to the Laundry Department in New York. Although less glorious than Eastman’s service, logistics are a critical component of an operating military force. Dalitz’s value to the Quartermasters Corps is reflected by his career. Shortly after Private Dalitz joined the corps, the Army commissioned him as a second lieutenant and placed him in charge of the Laundry Department in New York. Dalitz elected to live at the Hotel Savoy-Plaza, and managed to comfortably continue to run his businesses, both licit and illicit, while serving. His department serviced U.S. troop ships and U.S. personnel overseas. Dalitz’s expertise reached beyond the fixed laundry facilities of the Army, and he was instrumental in getting mobile laundry services much closer to the troops in combat. The experiences of disease and illness from World War I’s trenches had taught a lesson in combat hygiene, and although there had been an early form of mobile laundry in 1918, improvements were drastically needed. Dalitz worked with the auto industry to design new mobile laundry units that were put into service in North Africa. While they were found to have some drawbacks, they were a vast improvement. Dalitz took great pride in his accomplishments. “I didn’t get overseas like I wanted to, but I did the next best thing, and I received a nice award for the work I did. It is considered to be a very coveted non-combatant award from the Second Service Command.” Dalitz was discharged from service at the end of May 1945, just a few weeks after the surrender of Nazi Germany.

Following the war, Dalitz channeled his experience with his illegal casinos in the Midwest toward the expanding Las Vegas gambling scene. He partnered with his Cleveland contacts to finance the completion of the Desert Inn hotel-casino. In Las Vegas, Dalitz’s casinos were legal, but his involvement was a significant factor in the legitimate casinos becoming infiltrated by the Mob, particularly the Midwestern Mob. Over time, he sold his interests in his casinos and turned to the development of Las Vegas into a tourist destination and convention hub. Dalitz also engaged in an array of philanthropic and business ventures that changed the face of Las Vegas, earning him the nickname “Mr. Las Vegas.”

Dalitz was cagey about his ties to organized crime. In testimony to the Kefauver Committee, he only admitted to crimes that were old enough that he wouldn’t be prosecuted. Dalitz only faced criminal charges once in his life, and those were ultimately dropped.

Monk Eastman and Moe Dalitz were from different eras of organized crime, and had quite different military service experiences, but each contributed significantly in his own way. The U.S. military benefited from both men’s service, and both of them seemed to have valued their time and gained from it.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org