John Dillinger’s wooden gun and death mask preserve notorious moments in his life

The infamous outlaw’s spree of robberies and narrow escapes came to a bloody end 90 years ago today

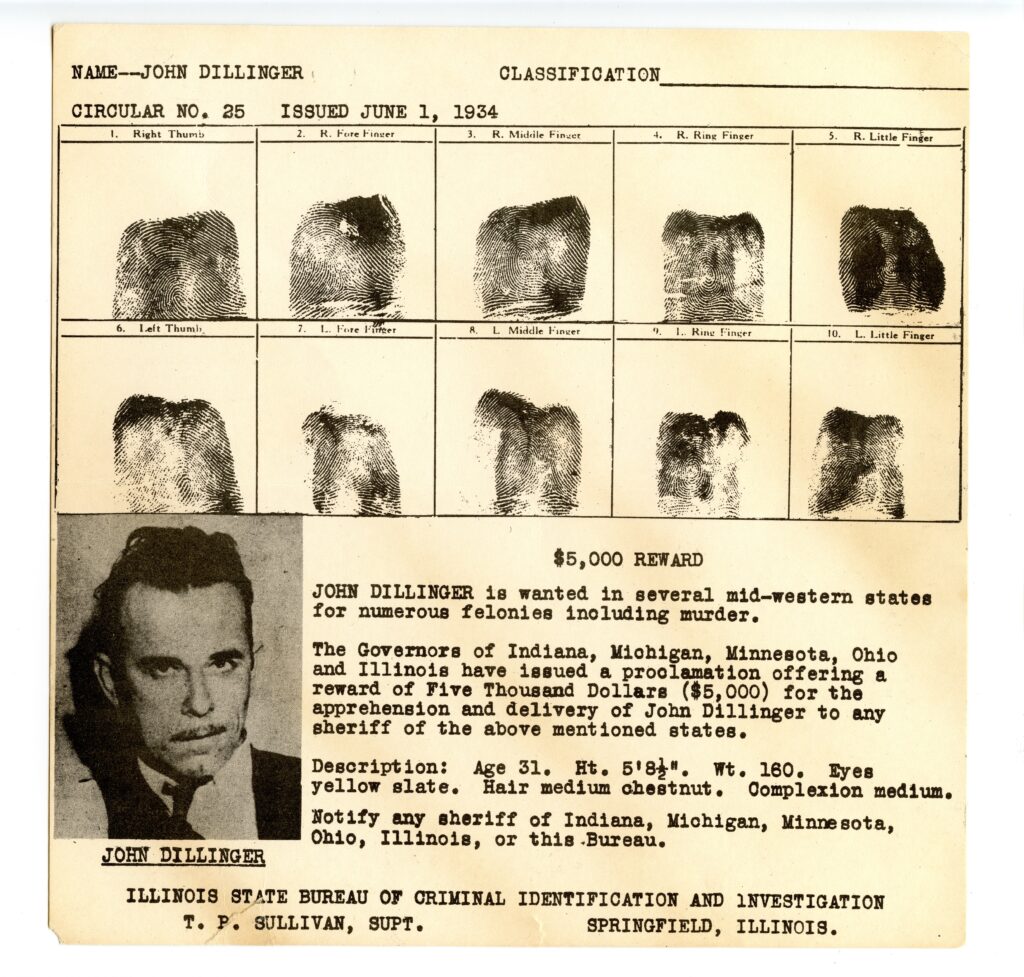

On July 22, 1934, “Public Enemy Number One” – John Dillinger – was killed by federal agents moments after he walked out of the Biograph Theater in Chicago. The cat-and-mouse game between the Dillinger Gang and law enforcement had finally reached its conclusion after 14 months.

Ten years earlier, Dillinger debuted on the criminal scene with life-changing consequences. At 21 years old, he robbed a grocery store owner. It was his first major crime. His well-meaning father encouraged him to plead guilty for lenience, but the judge doled out the maximum sentence. After nearly a decade behind bars, Dillinger came out a bitter and hardened man with underworld connections and training from veteran bandits.

Dillinger began robbing banks only a month after his parole in May 1933. He also paid a visit to Indiana State Prison and threw guns over the wall to help his buddies – and future Dillinger gang members – escape. Dillinger had been arrested by the time they pulled off their escape, so the fugitives returned the favor. Eight of the escaped inmates broke Dillinger out of jail in Lima, Ohio, and killed Sheriff Jesse Sarber in the process.

With his new gang in tow, Dillinger spent the rest of 1933 robbing banks and police armories. When the new year rolled around, most of the Dillinger gang had gone to Tucson, Arizona, to find a new hideout. Meanwhile, Dillinger led a smaller crew to rob a bank in East Chicago, Indiana, on January 15, 1934. During their getaway with $20,000, Dillinger exchanged fire with Officer William O’Malley and killed him. The gang had a short-lived reunion in Tucson before they were arrested on January 25.

The wooden gun escape

Dillinger was extradited to Indiana to face charges for the murder of Officer O’Malley. Authorities flew him to Indiana and held him at the Lake County Jail in Crown Point. Despite calls to move the prisoner to the higher-security state penitentiary in Michigan City, Sheriff Lillian Holley was confident the local jail was more than enough to contain him.

“We do not expect to have any trouble with our newest prisoner,” Holley told reporters. “Of course, I warned him the first thing that we would stand for no monkey business. If he starts anything there will be a half-dozen deputies about the place with machine guns to take care of him.”

The jail did not hold him. Dillinger escaped on March 3, 1934.

The details of the escape were revealed by Dillinger’s attorney, Louis Piquett, in interviews with G. Russell Girardin, whose unpublished 1935 manuscript was released by William Helmer in 1994 as Dillinger: The Untold Story. Dillinger’s first idea was to have his gang bust him out with dynamite, but that didn’t pan out. He then asked Piquett to get him a gun, but Ernest Blunk, the sheriff’s deputy who was on the take, refused. Dillinger settled for the next best thing: a wooden gun.

While Dillinger later claimed he whittled the wooden gun himself, it was the attorney’s investigator, Arthur O’Leary, who procured the gun from a woodworker. On the morning of the escape, the gun was delivered to Dillinger.

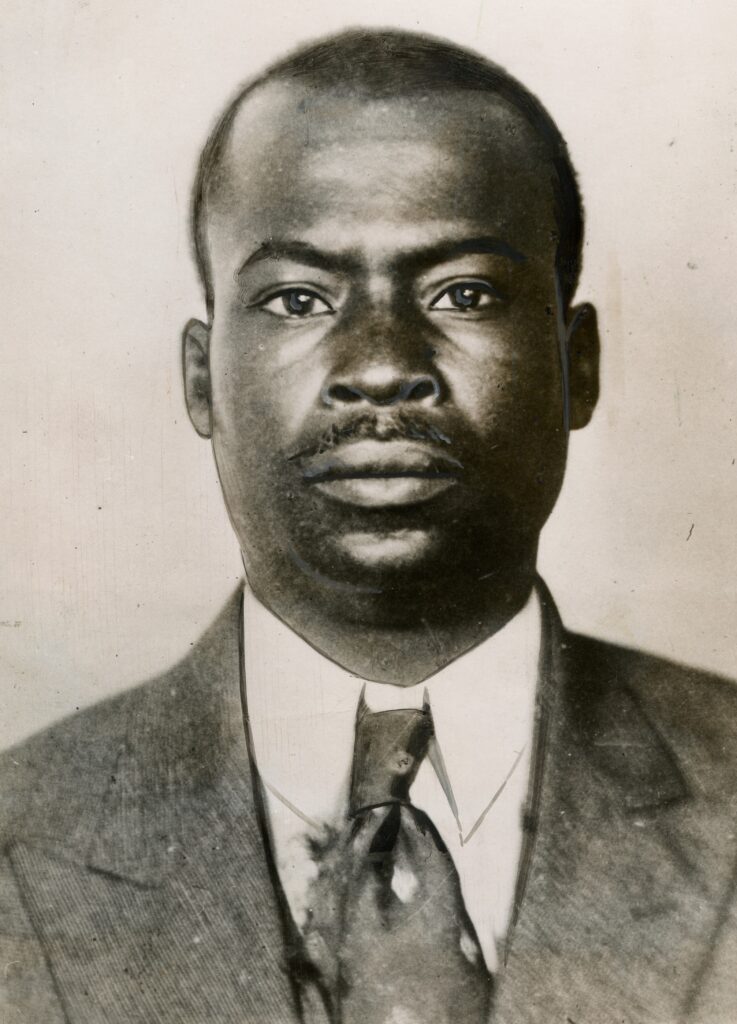

While out of his cell for exercise, Dillinger pressed the fake gun into a prison trustee’s back and, with the help of Deputy Blunk’s convincing performance – he was later acquitted for lack of evidence – began forcing the prison guards into jail cells. Herbert Youngblood, a Black inmate and murder suspect bound for death row, joined Dillinger in his escape.

At first glance, the wooden gun is not terribly convincing. The 5.75-inch piece of wood has a quarter inch-diameter safety razor handle as the “barrel” and two nails on either end to simulate the sights. Shoe polish gives the gun it’s dark finish. It also lacks a grip.

Dillinger didn’t need the wooden gun to stand up to close scrutiny for his escape to work. It only had to work long enough for Dillinger to obtain real guns. Once Dillinger and Youngblood found two Thompson submachine guns, the wooden gun’s job was over, which Dillinger smugly pointed out to the now-confined warden and guards.

Edwin (sometimes mistakenly called Edward) Saager, a mechanic paid off to supply a getaway car, had Sheriff Holley’s 1933 Ford V-8 ready for Dillinger’s escape. With Blunk and Saager as “hostages,” Dillinger and Youngblood escaped to Illinois where they parted ways. Youngblood was killed in a shootout with police two weeks later.

In the coming days, the harshest criticism from the press was laid on the “lady sheriff.” One report wrote she “became hysterical” and “shrieked into the telephone” when she learned of Dillinger’s escape. Sheriff Holley defended her actions and placed the blame on those who were at the jail when he escaped. “I feel that I’m getting the blame for this just because I’m a woman. I can’t see where I was at fault,” Holley told the Chicago Tribune.

Humorist Will Rogers agreed with her: “You can’t blame that woman sheriff so much after all because she thought she was depending on men!” In a post-escape visit to his home in Mooresville, Indiana, Dillinger reportedly said to his father, “Will Rogers doesn’t know how close he hit to the bull’s eye with that one.”

Sheriff Holley was clear about what would happen to Dillinger if he returned to Crown Point in a remark to the judge in the Dillinger case: “If I get him back, you won’t try him, judge. You may try me instead.”

War on “public enemies”

The response to the epidemic of folk-hero bank robbers transformed federal law enforcement. J. Edgar Hoover originally envisioned his fledgling Bureau of Investigation (renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1935) as a force of lawyers and accountants who took down criminals with paperwork. He was reluctant to get involved with the problem of violent crime. The Kansas City Massacre in 1933 changed all that when a group of law enforcement officers, including one of Hoover’s agents, were ambushed and killed in a botched attempt to free bank robber Frank “Jelly” Nash. Hoover learned the hard way that FBI agents needed to be armed after losing four agents between June 1933 and November 1934.

In response, Attorney General Homer Cummings and President Franklin Roosevelt became dedicated to fighting crime on a federal level. 1934 saw a slew of new laws passed: federal agents received a congressional mandate to carry firearms, robbing banks became a federal crime, and the feds could pursue stolen cars and kidnappers across state lines.

Dillinger crossing into Illinois with the sheriff’s stolen car put him in the FBI’s crosshairs. From March to July, federal and local law enforcement played a cat-and-mouse war of attrition with the Dillinger Gang. Dillinger’s allies were gradually arrested, wounded or killed during each skirmish.

While hiding out in Chicago in May 1934, the increasingly desperate Dillinger had plastic surgery to change his facial features and attempted to have his fingerprints surgically removed, although they eventually grew back mostly intact. With a new face, Dillinger committed his final bank robbery on June 30, 1934, in South Bend, Indiana, alongside Homer Van Meter and “Baby Face” Nelson. Shortly after, Dillinger found a new hideout at the Chicago home of brothel madam Anna Sage (née Cumpănaș), an association that would have fatal consequences.

The death of Dillinger

On July 22, 1934, Dillinger went to the movies with two lady companions, Sage and Polly Hamilton, a new girlfriend after Billie Frechette was arrested three months earlier. He had fittingly gone to see Manhattan Melodrama, a gangster movie starring Clark Gable.

Sage, trying to stave off her looming deportation, secretly met with Melvin Purvis, the special agent in charge of the FBI’s Chicago field office, and revealed Dillinger’s theater plans.

Dillinger walked out of the theater with the two women to an ambush. The agents knew it was Dillinger because Sage wore an orange skirt as a signal, which led to the press mistakenly labeling her the “woman in red.” As Dillinger fled down an alley, he was shot from behind. The bullet entered through the back of his neck and exited under his right eye.

Dillinger’s older sister, Audrey Hancock, identified his body in the morgue. His body received many more visitors, including those who wanted to make a death mask of the slain outlaw. Four different molds were created of his face of varying quality. The funeral home director later noted that Dillinger’s face was missing facial hair and skin from all the molds.

Harold May, president of the Reliance Dental Supply Company, made the second mold of Dillinger’s face, supposedly to show off a new mold-making material called “Reprolastic.” May sent a cast of the death mask to FBI Director Hoover, who allowed trainees at the FBI National Academy to make copies of the mask as part of a forensic modeling training program.

Before the advent of photography, death masks preserved the appearance of deceased famous people, such as Beethoven, Sir Isaac Newton and Mary Queen of Scots. The masks served as references for sculptures and portraits. Death masks took on renewed interest in the 1800s because of phrenology, the belief that the size and shape of the skull and face revealed psychological characteristics, often used to justify racism, classism and sexism. The practice of making death masks was uncommon by 1934, but America’s Dillinger fever made an exception.

Dillinger’s death was just one of the successes the FBI had in its crusade against bank-robbing outlaws. By the end of 1936, most of Hoover’s “public enemies” were either dead or in custody. The newly armed FBI could now go toe-to-toe with well-armed criminals, although it would be a few decades before they would take an active role in the fight against America’s organized crime syndicates.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org