The Kansas City Massacre prompted legal reforms that bolstered federal law enforcement

Shootout 90 years ago triggered the FBI mission to take out ‘public enemies’ such as Pretty Boy Floyd and John Dillinger

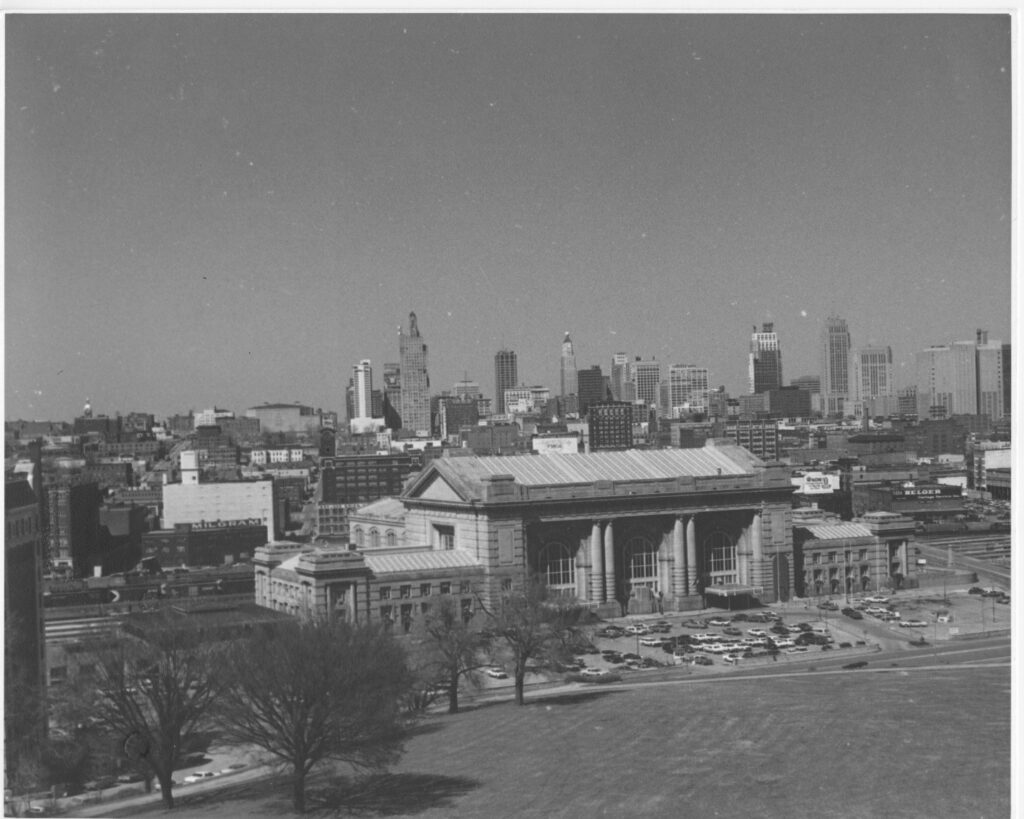

On June 17, 1933, an ambush at Kansas City’s Union Station railroad depot left five men dead and two wounded. An agent of the Bureau of Investigation (later known as the FBI), a police chief and two detectives were among the fatalities.

The shootout, which came to be called the Kansas City Massacre, spurred Congress to pass a series of crime bills that included the first federal gun control law and a mandate for federal law enforcement officers to carry firearms. It also was the trigger for FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s crusade against bank-robbing hoodlums – his “public enemies.”

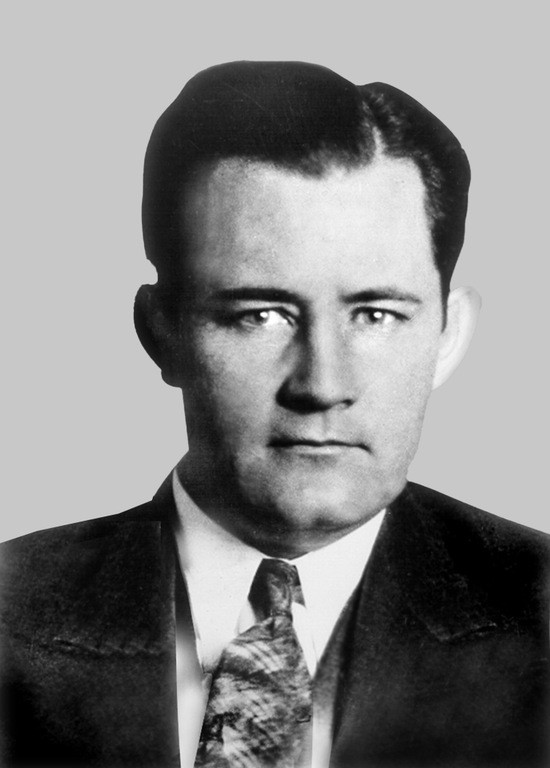

At the center of the Kansas City Massacre was Frank Nash, a prolific bank robber with a knack for cracking safes using nitroglycerin. After receiving a life sentence in 1913 for shooting his crime partner in the back, he was granted a pardon by enlisting to fight on the Western Front during World War I.

During his second prison sentence – 25 years this time for burglary using explosives – Nash got out early for good behavior. Once again in prison for train robbery in 1924, Nash remained at Leavenworth until his prison job gave him the opportunity to walk away on October 19, 1930. After he helped seven more prisoners escape the following year, the FBI decided to hunt him down. They tracked him to Hot Spring, Arkansas, and he was apprehended on June 16, 1933. That night, Nash and his law enforcement escorts boarded a Kansas City-bound train set to arrive early the following morning.

Hot Springs chief of detectives Herbert “Dutch” Akers tipped off Richard Galatas, an associate of Nash in town, that the FBI was en route to Kansas City with their prisoner in tow. Galatas sounded the alarm, and soon Vernon Miller, a bootlegger and former South Dakota sheriff, was tasked with freeing Nash from his captors. An old acquaintance of Nash, Miller couldn’t free his friend alone, so he headed to a Kansas City brothel where he recruited two well-armed fugitive highwaymen: Adam Richetti and Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd. Having obtained the manpower – and firepower – he needed, Miller led the trio to Union Station where they waited for their quarry to arrive.

Escorting Nash on the train were Otto Reed, police chief of McAlester, Oklahoma, and two FBI agents: Frank Smith and Joseph Lackey. Upon arrival, they were met by Special Agent in Charge Reed Vetterli and agent Raymond Caffrey, as well as Kansas City detectives Frank Hermanson and William Grooms. After receiving the all clear, the lawmen led Nash to a Chevrolet parked outside the station. While they were loading the prisoner into the vehicle, two armed men emerged from behind a nearby car and unleashed a hail of bullets. While the lawmen were armed with shotguns and pistols, they were no match for the lethal efficiency of the outlaws’ submachine guns. In the aftermath, the two detectives and agent Caffrey were lifeless on the ground outside the car. Inside, the police chief was dead, as was Nash, betrayed by friendly fire. Having botched their mission, the assailants fled.

Vernon Miller fled to Chicago first before making his way to the East Coast, hoping to find work with Murder Inc. boss Louis “Lepke” Buchalter. Wherever Miller went, the FBI followed, however, and he became a liability for Buchalter. In November of 1933, Miller’s body was found in a ditch outside Detroit after Miller allegedly killed one of Longie Zwillman’s underlings and was bumped off in retaliation.

“Pretty Boy” Floyd and Adam Richetti fled together and went into hiding, posing with two sisters as couples for cover in New York. In October 1934, they decided to go back to Oklahoma. After a car accident in Ohio, Floyd and Richetti attracted the attention of local police, escalating into a firefight that left Richetti captured and Floyd on the run. Two days later, an FBI squad, led by renowned G-Man Melvin Purvis, tracked down and killed Floyd. In 1938, Richetti was convicted of murder and became the fifth person executed in the Missouri State Penitentiary gas chamber.

Following the Kansas City Massacre, efforts to prevent future tragedies were swift. If the bureau had to go toe to toe with bandits brandishing machine guns, they needed to boost their arsenal. A week after the ambush, Kansas City Special Agent in Charge Ralph Colvin wrote to Hoover requesting more guns:

“We ought to have one Thompson sub-machine gun, a couple of high-power rifles and about four 45 calibre Colts [sic] Automatic pistols and plenty of ammunition for each. A saw-off shotgun or two would also be useful. I hate to send agents out after these outlaws unless we can meet them on equal footing.”

Director Hoover promptly wrote back: “I fully agree with you that our men must be afforded every possible facility in dealing with the type of men responsible for the cowardly acts committed at Kansas City.”

In fact, Hoover was one step ahead of Agent Colvin. On June 20, 1933, Hoover ordered two Thompson submachine guns for delivery to the Kansas City field office. Hoover also organized a committee to determine which firearms equipment would be best to supply to agents across the country. The result was that all field offices would receive .38 Special revolvers, .30-06 Springfield rifles, Remington or Winchester 12-gauge automatic shotguns and Thompson submachine guns. The next step would be to get Congress on board with allowing agents to carry firearms without restriction.

Contrary to popular belief, federal agents were allowed to carry firearms before the Kansas City Massacre. But the firepower was limited, as wrote Agent Colvin in his plea to Hoover: “We have only the small light pistols furnished by the Bureau and which are entirely inadequate for the purpose.” Without a congressional mandate to override local and state laws, agents had to follow the same rules as private citizens and obtain the requisite permits. This increasingly became an issue as bank robbers with fast getaway cars began speeding across state lines.

In 1934, Congress passed a slew of crime bills that strengthened federal law enforcement. The new laws also brought bank robbers under federal jurisdiction by making it a federal crime to flee across state lines, rob a bank tied to the Federal Reserve and extort or kidnap for a ransom. Congress officially granted the FBI the authority to make arrests and serve warrants for federal crimes and, of course, carry firearms. Lastly, the National Firearms Acts regulated all firearms except revolvers, pistols and rifles and shotguns with barrels more than 18 inches long. The legislation required said firearms to be registered through the Treasury and levied a $200 tax on any transfer to discourage law-abiding gun owners from supplying criminals. That tax is still in effect today, though the fee has not changed since 1934.

To arm up and fight these gangsters, Hoover needed a proper training facility to instruct agents in handling the newly acquired munitions. In 1934, the Marine Corps invited the Bureau to use its firing ranges in Quantico, Virginia, which would eventually become the FBI training academy. Now, properly armed and trained, agents were ready to take to the field and go after Hoover’s “public enemies.” In 1934, the FBI gunned down John Dillinger and George “Baby Face” Nelson and captured George “Machine Gun” Kelly. Shortly after, the Barker-Karpis Gang was decimated with the deaths of Ma and Fred Barker in 1935, and the capture of Alvin “Creepy” Karpis in 1936.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org