Happy New Beer’s Eve!

On April 7, 1933, Americans celebrated the ability to legally drink beer after 13 years of Prohibition

On the evening of April 6, 1933, lines formed outside of bars and breweries. In Chicago, WGN Radio broadcast special programming onsite at Atlas Brewing Company as it got ready to deploy a fleet of trucks filled with kegs and bottles of beer for the first time in 13 years. Radio host Quinn Ryan described the beer manufacturing and packaging process to listeners. CBS Radio broadcast segments on breweries across the Midwest — focusing its attention on the brew-hubs of St. Louis, Milwaukee and Chicago.

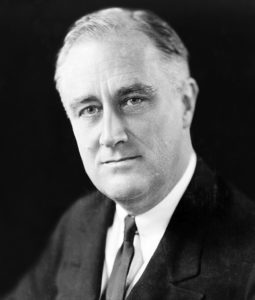

A few weeks earlier, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed the Cullen-Harrison Act, which legalized beer for the first time since Prohibition went into effect in 1920. For the first time in 13 years, Americans could drink legally obtained alcohol, and they were ready. An article in the April 8, 1933, edition of The New Yorker suggested, “Your guess is as good as anybody’s as to the larger social changes the return of beer will bring, but one thing seems certain: Beer gardens are going to spring up all about you.”

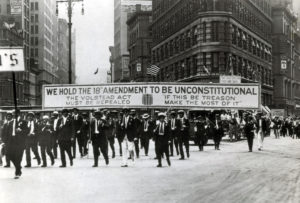

When Roosevelt took office in March 1933, Congress had already passed the repeal of Prohibition, but states had not yet completed the process of ratifying the 21st Amendment. Whereas outgoing President Herbert Hoover took a strong position in favor of the 18th Amendment and its enforcement, Roosevelt encouraged Americans to vote in favor of repeal. Because of the immediate need to get the country out of the Great Depression, his first 100 days in office were focused on creating jobs and generating revenue. That time is best remembered by the establishment of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Civilian Conservation Corps and other New Deal organizations, but it also was when Roosevelt encouraged passage of a Prohibition stopgap.

Nine days after his inauguration, on March 13, Roosevelt delivered a message to Congress: “I recommend to the Congress the passage of legislation for the immediate modification of the Volstead Act, in order to legalize the manufacture and sale of beer and other beverages of such alcoholic content as is permissible under the Constitution; and to provide through such manufacture and sale, by substantial taxes, a proper and much-needed revenue for the government. I deem action at this time to be of the highest importance.”

Congress acted quickly. Representative Thomas H. Cullen of New York introduced legislation to the House, and Senator Pat Harrison of Mississippi introduced it to the Senate. The legislation called for the immediate relegalization of the sale, manufacture and distribution of beer with no more than 3.2 percent alcohol by weight. On March 21, a joint conference committee passed the Cullen-Harrison Act, and Roosevelt signed it into law the following day. It was set to take effect on April 7. After signing the bill, Roosevelt famously remarked, “I think this would be a good time for a beer.”

States had to pass concurrent legislation in order for the Cullen-Harrison Act to go into effect within their borders. Nineteen states passed laws that mirrored the April 7 start date, and six others legalized beer but established later start dates. Other states soon followed suit.

Americans across the country started planning festivities for April 7. In Washington, D.C., a private organization planned a “Beer Ball” to celebrate what was almost immediately coined “New Beer’s Eve.” Revelers planned an elaborate party in the Washington Auditorium that would rival a New Year’s party come the stroke of midnight April 7.

In celebration of the new law, brothers August and Adolphus Busch of Anheuser-Busch gifted their father with 12 Clydesdale horses. The horses then began their inaugural tour, traveling through the streets of St. Louis. The Busch family sent them by rail to New York City, where they delivered two cases of beer to former governor and famous “wet” Al Smith. Then they went to Washington, D.C., to deliver a case of beer to President Roosevelt.

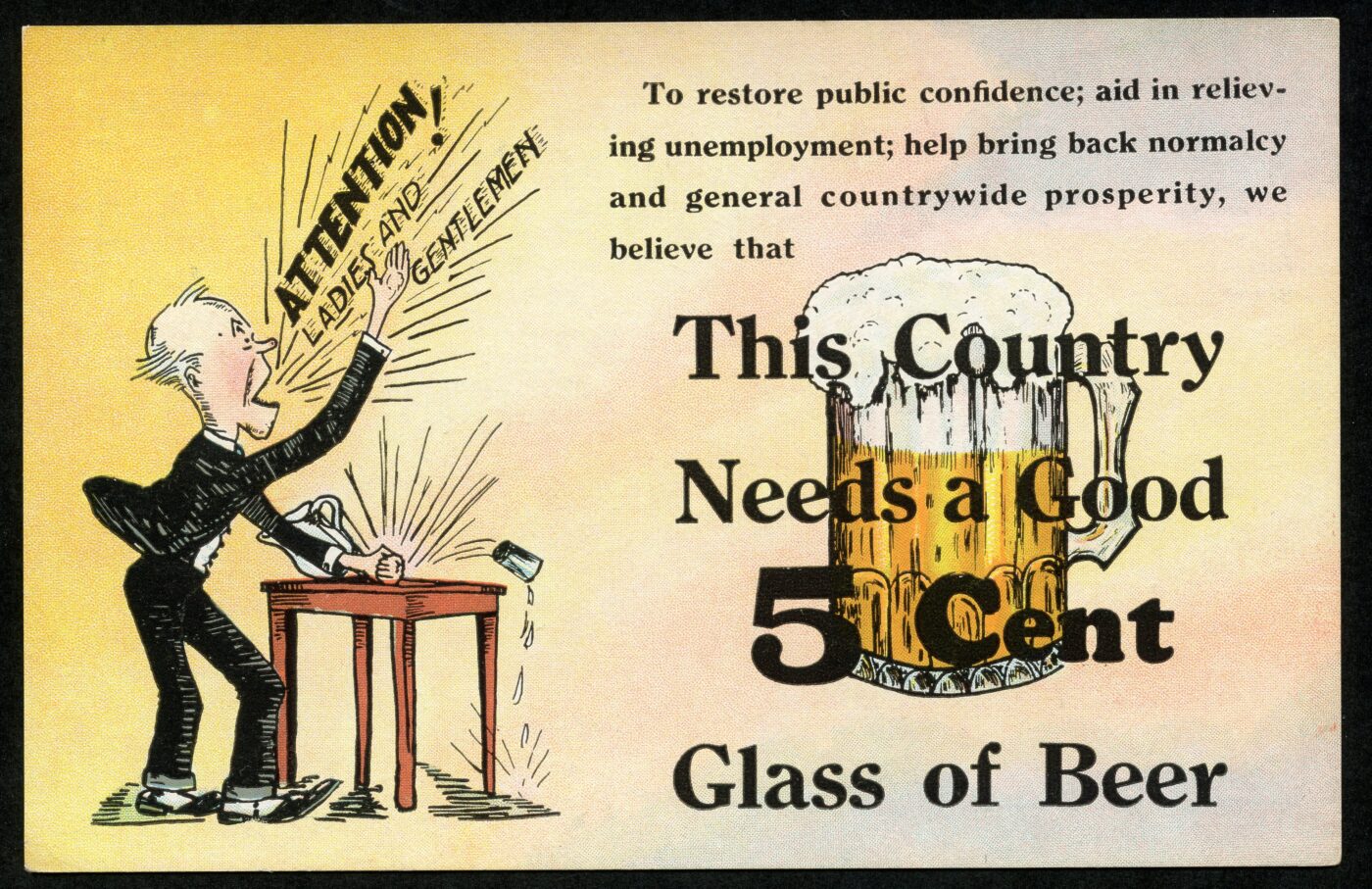

But it wasn’t all fun and games for thirsty consumers. In most major cities, Prohibition agents were out in the hours leading up to April 7, issuing tickets to people who celebrated a little early. In Reno, drinkers paid as much as 50 cents a beer on the first day of legal sales, thanks to a limited supply and an outsized demand. Before Prohibition, it was unheard of to pay more than 5 or 10 cents a beer, and even in illegal speakeasies, most people were paying 15 to 25 cents.

Breweries had just two weeks to make enough beer to quench America’s thirst, which was no small feat. During Prohibition, breweries around the country shuttered. In New York City, there were 70 breweries in 1919. By 1933, only 23 survived. The American breweries that did stay open during Prohibition were reduced to smaller work forces, and some of them had been physically modified to make alternative products. For instance, Pennsylvania brewery Yuengling made ice cream. Coors diversified into the manufacture of malt syrup and porcelain. Anheuser-Busch made at least 25 alternative products, including frozen eggs, soft drinks, home-brewing ingredients and even automotive parts.

Most breweries also made “near beer,” beer brewed and then stripped of its alcohol. Although it was sold as a healthy, nonalcoholic alternative to beer, many people would use it to make “needle beer” by placing a needle through a beer bottle or keg’s cork and infusing the liquid with alcohol. Near beer is made in a nearly identical manner as real beer. The only difference is that before bottling and aging, it is heated or vacuum distilled so the alcohol is removed. Near beer was generally made from lower-quality ingredients and was not aged as long as normal beer.

Many breweries prepared for New Beer’s Eve by just skipping the final step of removing alcohol from near beer recipes that were already in production. This meant they could more quickly and efficiently build up their stock, but it led to lower-quality beer.

Breweries hired new employees to make all of this happen – brewers, bottlers, truck drivers, delivery men. Restaurants, hotels, and groceries also accurately anticipated an increase in business. But bootleggers, rumrunners, moonshiners and speakeasy proprietors were not as excited. In the April 15 edition of The New Yorker, reporter Morris Markey spoke to speakeasy owners about how the first week of legal beer was affecting them. One anonymous proprietor explained that the speakeasies hidden behind upscale restaurants still had some life left in them but, “The decent, average speakeasy: good food and reasonably priced drinks and respectable dinner trade — all that is done with. Most of them will go bankrupt.”

To illustrate the increasingly sluggish bootlegging industry, a May 4, 1933, article in North Carolina’s Roanoke Rapids Herald, “Liquor Cases on Decline,” reported only three Prohibition violation cases and 10 total criminal cases tried in the county court that week, down from about 20 per week in previous years. Similar decreases in Prohibition violations occurred across the country. And as criminal cases decreased, tax revenue increased. By 1933, states were weary from enforcing Prohibition, and now there was something more lucrative to pursue: tax evasion.

Legal beer was great for thirsty Americans and government coffers drained from the raging Great Depression, but the mobsters who made millions off Prohibition had little to celebrate. Bootleggers, speakeasy proprietors and others could see the writing on the wall. They could still turn a profit as long as only low-point beer was available, but they would need to diversify to stay solvent after full repeal, which would occur on December 5, 1933. They invested their profits in new, or at least different, ventures. Many mobsters shifted focus to casinos and other forms of gambling, which paved the way for their eventual migration to Las Vegas.

On April 6 and 7, raise a glass to legal beer! The Mob may not have celebrated the Cullen-Harrison Act, but Americans everywhere can be glad it brought back beer 86 years ago.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org