Fifty years ago this spring, Mario Puzo changed the way we view organized crime

The Godfather novel was a best-seller that spawned two legendary movies

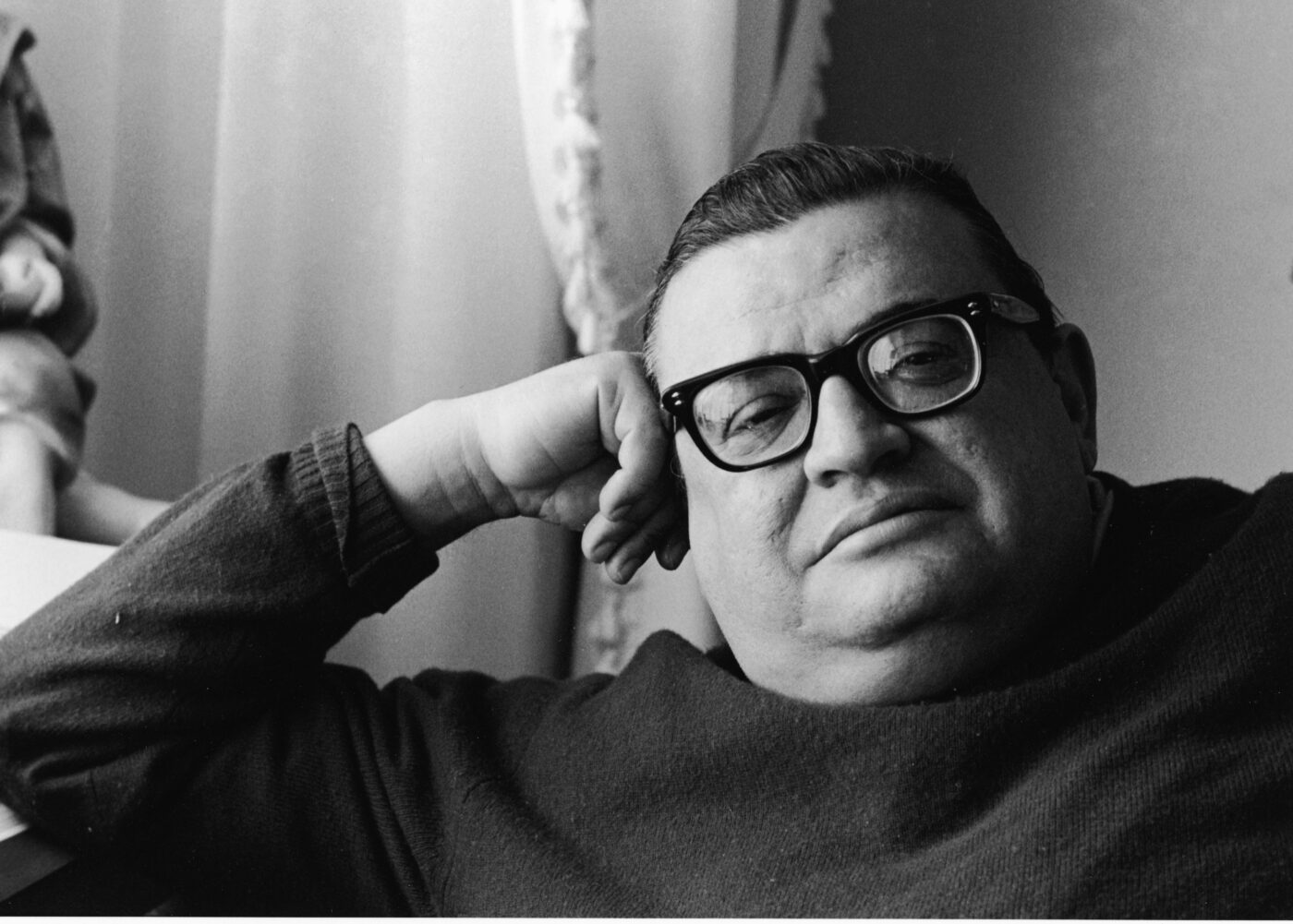

Mario Puzo needed money. His first two novels, The Dark Arena (1955) and The Fortunate Pilgrim (1965), received good reviews but were not best sellers. He had an idea for his next novel, but his publisher wasn’t seeing dollar signs attached to it.

“I was 45 years old and tired of being an artist,” Puzo wrote in The Godfather Papers and Other Obsessions. “I owed $20,000 to relatives, finance companies, banks and assorted bookmakers and shylocks. It was really time to grow up and sell out as Lenny Bruce once advised.”

Puzo didn’t want to write about the Mafia, as his editors had suggested, but he knew it was a subject that would sell. A $5,000 advance from G.P. Putnam got him motivated. Still, it took him three years to complete the manuscript.

He based his story entirely on research. As he put it, “I never met a real honest-to-god gangster. I knew the gambling world pretty good, but that’s all.”

Puzo submitted the manuscript to Putnam in 1968, and, with the last installment of his advance, took his family to Europe. The vacation cost him a lot more money than he had. But when he returned, he learned that his publisher had sold the paperback rights to The Godfather for $410,000. His money problems were over.

The novel, released 50 years ago this spring, went on to become a No. 1 best seller in the United States, as well as in Europe. It was on the New York Times best-seller list for 67 weeks. Since then, it has sold more than 20 million copies and is still in print today.

In addition to selling well, The Godfather received generally positive reviews. The legendary sportswriter Dick Schaap, in a review for the New York Times, recognized the novel’s faults but praised its cumulative appeal. “Allow for a touch of corniness here. Allow for a bit of overdramatization there. Allow for an almost total absence of humor. Still, Puzo has written a solid story that you can read without discomfort at one long sitting. Pick a night with nothing good on television, and you’ll come out far ahead.”

Although journalists and historians had been documenting the inner workings of the Mafia for years, it was Puzo who introduced the general public to the traditions, hierarchies and activities of Italian-American crime families. His story, centered on the Corleone family, is a narrative of a growing Mob war in New York and of who will take over the family when Don Vito Corleone dies.

It was a natural story for the big screen, and Hollywood took notice.

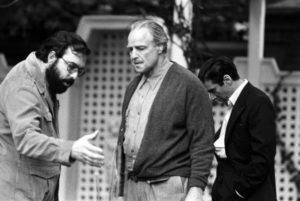

The Godfather movie paid even bigger dividends for Puzo, who signed on to write the screenplay. He worked on the early drafts in New York and Los Angeles in 1970, then collaborated with director Francis Ford Coppola on revisions in 1971.

As work progressed on the film, the Italian-American Civil Rights League began to express concerns about whether the movie would stereotype Italian-Americans. Producer Al Ruddy promised to take out all references to the Mafia in the script, and the League pledged to cooperate. Puzo said this was a brilliant move on Ruddy’s part, “because the word ‘Mafia’ was never in the script in the first place.” In fact, according to Ruddy, there was a single Mafia reference that had to be excised.

The movie earned more money than any other film in 1972, and it won Best Picture at the 1973 Academy Awards. The sequel, The Godfather: Part II, released in 1974, received comparable accolades. The performances by Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Robert Duvall, James Caan and Diane Keaton helped cement their places in the Hollywood pantheon.

The Godfather’s cultural influence has been profound, from its sensitive portrayal of Italian Americans to its contributions of enduring words and phrases to the language. Tom Santoprietro, who wrote a book called The Godfather Effect, says the movie transformed Hollywood. “It made Italians seem like more fully realized people and not stereotypes,” he told Smithsonian magazine in 2012. “It was a film in Hollywood made by Italians about Italians.”

Santoprietro said Italian-Americans have come to embrace the film because “it squashed the idea that Italians were uneducated and that Italians all spoke with heavy accents. Even though Michael (Corleone) is a gangster, you still see him as the one who went to college, pursued an education and that Italians made themselves a part of the New World. These were mobsters, but these were fully developed, real human beings.”

While few may see Puzo’s third novel as a literary masterpiece, there is no discounting its enduring appeal. Consider the weight and portent of this excerpt from Puzo’s description of Don Vito Corleone:

“[He] was a man to whom everybody came for help, and never were they disappointed. He made no empty promises, nor the craven excuse that his hands were tied by more powerful forces in the world than himself. It was not necessary that he be your friend, it was not even important that you had no means with which to repay him. Only one thing was required. That you, you yourself, proclaim your friendship. And then, no matter how poor or powerless the supplicant, Don Corleone would take that man’s troubles to heart. And he would let nothing stand in the way to a solution of that man’s woe. His reward? Friendship, the respectful title of ‘Don,’ and sometimes the more affectionate salutation of ‘Godfather.’ … It was understood, it was mere good manners, to proclaim that you were in his debt and that he had the right to call upon you at any time to redeem your debt by some small service.”

The Godfather was so convincing that plenty of real-life wiseguys embraced it. Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, underboss to John Gotti in the 1980s, had nothing but praise for the movie in his memoir, Underboss:

“I left that movie stunned,” he said. “I mean, I floated out of the theater. Maybe it was fiction, but for me, then, that was our life. It was incredible. I remember talking to a multitude of guys, made guys, everybody, who felt exactly the same way. … The Mob end was so on the money, it was crazy. It was basically the way I saw the life.”

The down side to The Godfather’s success is that it has glorified organized crime in some people’s eyes. The well-rounded depictions of the characters have had the side effect of making those characters and their lifestyles appealing. Some people admire the Corleones – and, by extension, their real-life counterparts – despite the fact that they are largely unrepentant criminals engaged in heinous acts of treachery and murder.

It was not Mario Puzo’s intention to glorify the Mob – he just wanted to get out of debt by writing a novel that lots of people would want to read. Readers and moviegoers should be able to distinguish between the absorbing fiction of The Godfather and the dark reality of organized crime.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org