Body farms unravel mysteries of human decomposition

Forensic evidence about murder victims is more plentiful and accurate today thanks to body farm research

In May of 1983 in New Jersey, a cyclist stumbled upon a turkey vulture feeding on something in a black plastic bag. Upon closer inspection, it was a human arm. Flies and carrion beetles had long been feasting on the flesh as the medical examiner removed the plastic from the body. Only the wallet and family photos found on the corpse revealed the identity of the victim as Daniel Deppner. Deppner had been poisoned and shot point blank in the head. The body was too far decomposed to give any clue about how long Deppner had been dead. The only clue was when Deppner was reported missing.

A few months later, police found another body in Orangetown, just north of the New Jersey-New York border, under curious circumstances. The corpse appeared to be fresh with little decomposition. Corpses typically begin to decompose from the bacteria inside the body, but in this case the body had more decay on the outside than inside. During the autopsy, the coroner found evidence of ice crystals in the victim’s heart. The body appeared fresh because it had been frozen. Investigators were fortunate that the culprit was in a hurry and did not properly thaw the body, or else they would have never realized the victim died more than two years before. A missing persons report confirmed this was Louis Masgay.

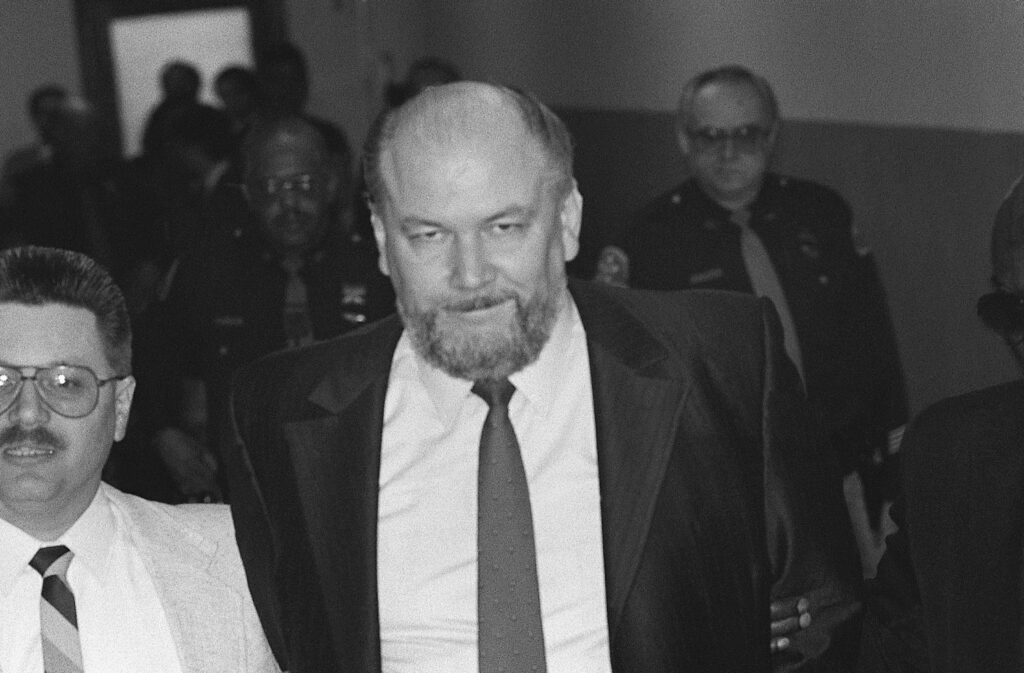

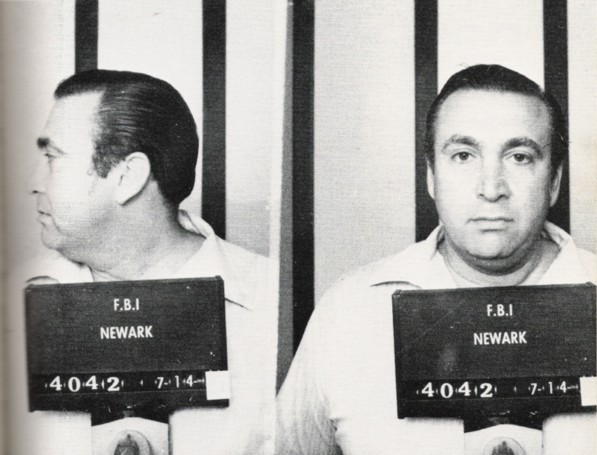

Deppner and Masgay were both associates — and now victims — of Mob hitman Richard Kuklinski.

Kuklinski had already committed a number of murders by the time he began his career with the Mob. He started doing occasional jobs for the DeCavalcante family in New Jersey. Later, he became involved with a like-minded killer, Gambino family hitman Roy DeMeo of New York. DeMeo and his crew perfected a system of murder called the “Gemini method.” They would lure a target into an apartment next to DeMeo’s Gemini Lounge bar where, after a shot to the head, the crew would drain the body of blood and dismember the corpse for easy disposal. Kuklinski worked with DeMeo’s crew as an enforcer. Kuklinski’s murders were not limited to Mob hits, however. Deppner was an associate in Kuklinski’s breaking-and-entering crew. Masgay was a customer for fencing hijacked VHS tapes.

The personal effects found on Deppner and Masgay’s bodies were the only clues to identify them and provide evidence for the post-mortem interval (PMI) – how long they had been dead. Deppner’s body was too decomposed for any accurate biological estimate. Masgay’s frozen corpse left no pathologic clues for time of death. Had Kuklinski tried to hide the victim’s identity by removing personal effects and fingertips, as he had done in previous cases, determining the PMI may have been impossible. Forensic anthropologists at the time were unable to determine PMI for a well-decayed corpse. There was room for improvement that the University of Tennessee’s Forensic Anthropology Center (FAC) had just recently begun to explore.

In 1977, University of Tennessee forensic anthropologist William Bass was called in by the local sheriff to consult on a puzzling case. Apparently grave robbers had placed a murder victim in the disturbed grave of Confederate Lieutenant William Shy. Bass estimated the post-mortem interval at six months to a year based on the condition of the victim’s body. However, as more evidence became known, Bass realized the “murder victim” was actually the expertly embalmed body of William Shy, well preserved in a sealed iron casket. From this experience, Bass recognized that forensic anthropologists needed to know a lot more about the decomposition process. In 1987, Bass opened the first anthropology research facility – later dubbed “the body farm” by a Patricia Cornwell novel in 1994.

Using human cadavers to study decomposition was a new concept in 1980, as the standard practice was to use pig cadavers as an analogue to humans in decomposition studies. Pigs and humans share many attributes, including body mass range, anatomy and hair coverage. Pigs are widely available, so researchers can control traits and the time and cause of death. However, pigs fall short of a perfect analogue concerning body proportions, stomach anatomy and diet. Recent studies have observed that pig cadavers decompose at a higher rate compared with human cadavers. Pig studies allowed researchers to know and understand the steps of decomposition, but the timing of said steps lies with human cadaver studies.

Researchers were initially reluctant to use human cadavers in decomposition studies because of several confounding factors. Unlike pigs, for human cadavers, researchers cannot control variables such as age and weight. Most donated human cadavers have died of natural causes, so the elderly make up a large portion of available cadavers. Humans also have dissimilar body chemistry thanks to factors such as diet and pharmaceutical use. Lastly, human cadavers may have been autopsied or frozen before arrival at the facility. Even with these limitations, it is still important to use human cadavers to understand how the human body decomposes.

The primary focus of body farms is forensic taphonomy (from the Greek taphos, meaning “burial”), which covers everything that happens to a body from death to discovery. Taphonomists observe how the human body decomposes in a controlled environment by studying the body itself as well as the impact the body has on its surroundings.

A corpse forms a localized ecosystem that attracts a variety of carrion organisms that feed on decaying tissue such as insects, bacteria and even vertebrates such as vultures. Species have adapted over time to have a favored stage in the decomposition process to minimize competition with other organisms. Blowflies and ants prefer the fresh stage at the beginning of decomposition. Adult flies lay their eggs in the corpse, which provides a crucial food resource for the newly hatched larvae. As the body begins to bloat from gases produced by flourishing bacteria, the odor becomes a signal for carrion beetles to join the feast. Predators such as wasps arrive not to feed on the corpse, but to prey on the foraging insects. Because each species has a preferred time to feed on a corpse, taphonomists study the assemblages of organisms feeding on a cadaver to estimate accurately the post-mortem interval.

Taphonomists also study environmental factors that influence the decay process. Bodies decay at different rates depending on temperature, weather and soil chemistry. Extreme cold or heat leaves detectable signatures on the body, such as microscopic cracks in the bones from the freeze-thaw cycles of water in the tissue.

More than 100 bodies are donated to the University of Tennessee each year. The body farm even arranges transportation for bodies within 100 miles of Knoxville. While medical schools return remains to the family after use, the FAC cleans the skeletal remains and maintains them in its anthropology collections, which contain more than 1,600 individuals ranging from fetal to 101 years old.

For nearly three decades, the University of Tennessee’s Forensic Anthropology Center was the only one of its kind. With the rise in popularity of forensic science in the 21st century, however, other universities started their own body farms. Today, there are nine body farms across the world, with seven of them located in the United States. Environment has a significant impact on decomposition, so it is beneficial for body farms to be located in different climates. In addition to Tennessee, there are body farms in Texas, Illinois, Colorado, North Carolina and Florida. Several more are in the planning phase and will begin construction when they secure funding. In 2016, the Australian Facility for Taphonomic Experimental Research became the first body farm outside the United States.

Forensic taphonomists work closely with law enforcement for training and consultation. Investigators apply these principals to cases to determine the time of death in conjunction with other evidence. With an ever-increasing library of decomposition data, Richard Kuklinski’s carelessly creative disposal of frozen bodies is no longer a foolproof way to disguise the time of death. Taphonomists have tested those and many other conditions in their outdoor laboratories. In recent years, the Tennessee facility has worked with Mexican investigators to train them on forensic excavation — a step toward resolving the many mass graves of drug cartel victims. Thanks to these recent advances in forensic taphonomy, it has become more difficult for killers to make a victim disappear. Any negligence will inevitably leave a clue for investigators to identify the victims and solve the case.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org