Sixty years later, ‘In Cold Blood’ murders still resonate

Historic Mob Museum building played pivotal role in arrests of Clutter family killers

As the sun set shortly after 5 p.m. on December 30, 1959, a driver stopped a 1956 Chevrolet at the front steps of the Las Vegas Post Office and Courthouse on Stewart Avenue. A stocky man, his hair styled in a greasy pompadour, emerged from the passenger side, limped up the steps and entered the lobby of the post office. The driver, taller, with shorter, dark blondish hair, stood outside the car waiting.

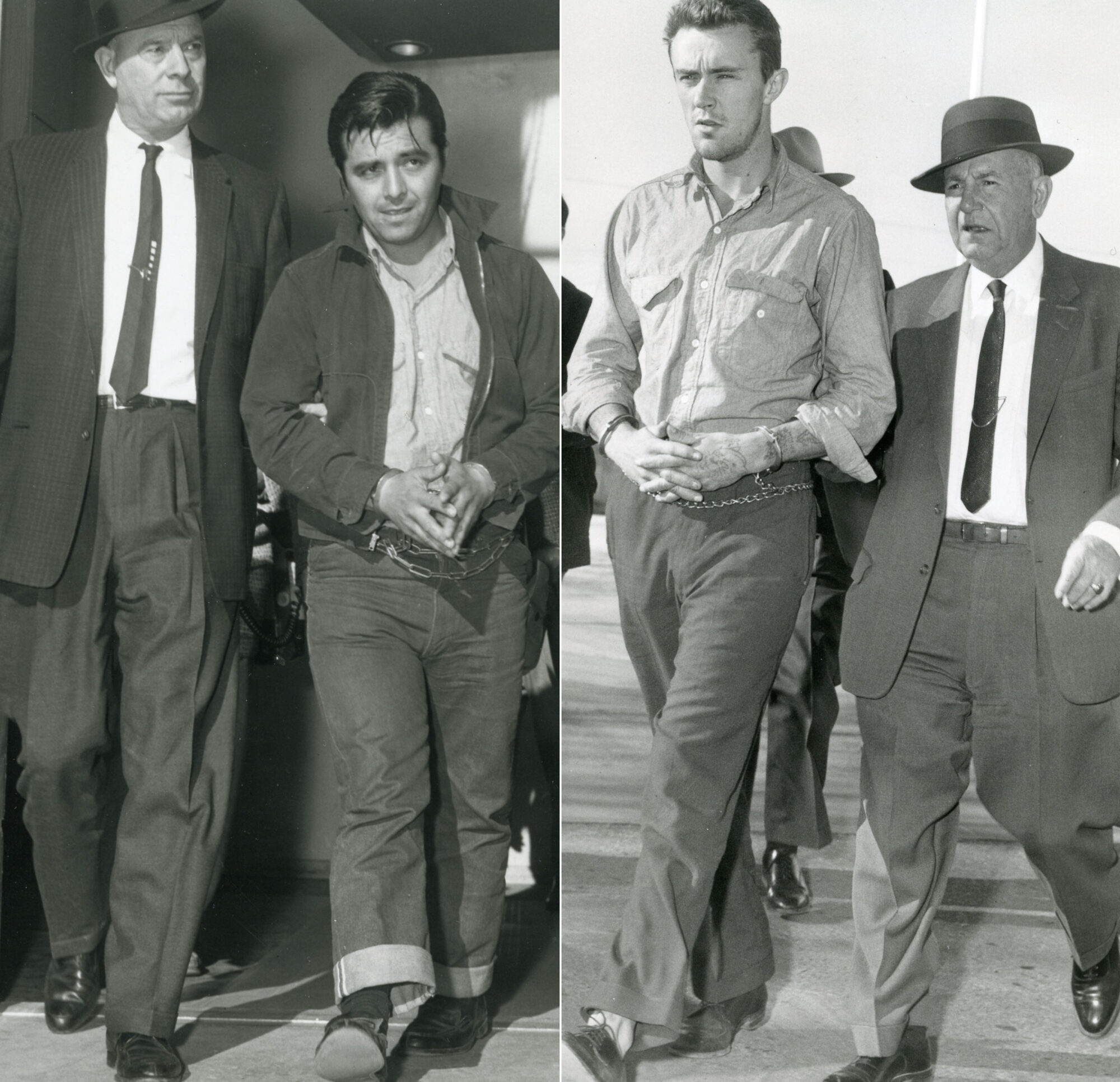

A pair of Las Vegas police officers patrolling in a marked sedan noticed the Kansas license plate from the rear of the Chevrolet. The patrol officers had the mugshots of two men, Richard Eugene Hickock and Perry Edward Smith, wanted for questioning in the November 15 shotgun murders of two adults and two teenagers in Kansas. On December 16, Harold Nye, an agent from the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, had visited Las Vegas, briefed police Lieutenant B.J. Handlon about the suspects and questioned Smith’s former landlady and local pawnbrokers. Police entered their names on an all-points bulletin.

Luckily, Hickock and Smith rolled into town and landed in the lap of law enforcement. The Las Vegas police officers, Ocie Pigford and Francis Macauley, noted that the Chevy’s Kansas state license plate, JO 16212, matched that of a reported stolen plate affixed to a stolen car. They watched as the stocky man – Perry Smith, his legs permanently damaged from a years-old motorcycle accident – awkwardly descended the steps of the courthouse, cradling a cardboard box, and slipped into the car.

The cops tailed the black and white Chevy as it sped west down Stewart to Main Street, turned left and, after several blocks, slowed opposite a two-story, arched Mission-style building, the Victory Hotel, on Main near Bridger Avenue. Pigford and Macauley pulled ahead of the Chevy, stopped, drew their guns and arrested Hickock and Smith on alleged parole violations. That was just to hold them for what was coming next. Earlier, a federal warrant charging Smith with unlawful flight and violating parole was filed in Kansas City by FBI Agent-in-Charge W. Mark Felt, who years later became famous as “Deep Throat,” the damaging source of stories about the Watergate scandal in the Washington Post that led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974.

It’s been sixty years since the cruel murders of four members of the Clutter family: father Herbert and mother Bonnie Mae, their daughter Nancy, 16, and son Kenyon, 15, in their farmhouse in the rural Kansas town of Holcomb on November 15, 1959. The slayings had nothing to do with organized crime, but have a special significance for the Mob Museum, now housed in the former federal building. It’s where police first spotted the suspects’ car and where Perry Smith entered to pick up the box – containing incriminating evidence – that he had mailed to himself for General Delivery during his road trip with Hickock to Mexico.

Hickock confessed in a statement made to Kansas Bureau of Investigation agents at the Las Vegas police station, saying that Smith killed the four victims. Smith declined to confirm or deny Hickock’s statement, then later, after leaving Las Vegas for Kansas with the agents, admitted he had in fact murdered them all.

The Clutters each died from a shot to the head by Smith with Hickock’s shotgun. The men first tied up the family members. They also taped their mouths, except for Nancy’s. This gave her the chance, in her horror, to get them to stop. According to Smith’s initial account, with the gun aimed at her, Nancy exclaimed “Oh, no! Oh, please. No! No! No! No! Don’t! Oh please don’t. Please!” before the twelve-gauge shot blasted into her head.

However, as Truman Capote wrote, “the confessions, though they answer how and why, failed to satisfy the sense of meaningful design. The crime was a psychological accident, virtually an impersonal act; the victims might as well have been killed by lightning. Except for one thing: they had experienced prolonged terror, they had suffered.”

The two men received death sentences in March 1960 and after unfruitful appeals, died after hanging from the gallows of the Kansas State Prison in Lansing in 1965. That gave Capote the ending he needed to complete his brilliant if flawed 1966 book on the Clutter murders, In Cold Blood.

Today, high school students read Capote’s fascinating tome, which he described as a “nonfiction novel.” His prose influenced American journalism, popularizing the use of fictional techniques in true crime and other genres in books and magazines, with writers injecting their own interpretations of the thoughts of real-life characters and making up dialogue based on educated guesses.

Across six decades, the case still resonates online, and remains controversial, with unresolved concerns among reporters, writers and enthusiasts. In 2012, police in Florida theorized that Hickock and Smith killed a second family of four, the Walkers, at a tenant ranch house in the town of Osprey near Sarasota, a little more than a month after the Clutter killings. Clifford and Christine Walker, their three-year-old son and two-year-old daughter were shot to death with a .22-caliber gun on December 19, 1959. Mrs. Walker had been raped.

Numerous witnesses claimed seeing Hickock and Smith in west Florida around that time. The men did travel in their stolen ’56 Chevy from Kansas through Florida, with Hickock writing a series of bad checks for cash, before making their way west, then south to Mexico and then Las Vegas. They bought things at a store in Sarasota several days before the Walker killings and stayed at a motel in Miami until the day before. The only highway running west and north out of Miami then was U.S. 41, which cut through Osprey. Witnesses placed the suspects in Tallahassee on December 21 or 22. Both men denied participation in the Walker slayings and passed polygraphs tests in 1960, but in the years since, experts have raised serious doubts about the reliability of the technology used in such tests back then.

The Sarasota County sheriff’s office persuaded a judge in 2012 to order the exhumation of the skeletal remains of Hickock and Smith, buried in a cemetery near the Kansas State Prison in Lansing, to take and compare DNA samples. Samples extracted from the men’s bone marrow failed to produce a match, but police said the decades-old evidence — semen found on Christine’s clothing — had deteriorated, making any test inconclusive. Sheriff’s deputies in Sarasota still regard Hickock and Smith as prime suspects.

In Cold Blood questions

The accuracy of Capote’s reporting in his 1966 book has been in dispute since it came out and remains a fashionable topic. As recently as 2017, a documentary about the murders on SundanceTV, Cold Blooded: The Clutter Family Murders, included an interview with a granddaughter of one of the two surviving Clutter daughters, who were not at the house at the time of the murders. The woman said the family objected to Capote’s portrayal of their home life, such as depicting Mrs. Clutter as reclusive and mentally ill.

“And so, where other people profited monetarily from the crime, we lost,” the unidentified granddaughter told People magazine. “The family has not profited from the book or movies and would have never taken money if it was offered.”

In the same People interview, the documentary’s producer, Joe Berlinger, described the Clutter clan as “terrific people who don’t understand why this story continues to fascinate people.”

Michael Nations, son of the late Mack Nations, a Wichita, Kansas, news editor, maintains that Capote objected to and helped block publication in New York of his dad’s 1962 manuscript based on Hickock’s prison letters to avoid upstaging In Cold Blood. He said Capote’s book relied too heavily on Smith’s account of what happened.

“People think that In Cold Blood was the gospel,” said Nations, who has posted videos about his father’s work on YouTube. “I don’t think it was that way at all. It’s not an honest story.”

Las Vegas connection

Smith, who listed Las Vegas as his residence, moved there briefly after his parole in July 1959. Driving a ramshackle used car, Smith had relocated and worked as a truck driver in Idaho when he received Hickock’s letter about the “cinch” of a “score” and asked him to partner with him on it. Smith returned to Las Vegas in his car and checked back into the Victory Hotel, a $9-a-week flop house and former brothel on Main Street. He sold the car for $90 and left town by bus on November 11. Four days later, he killed the Clutter family. When the two men returned to Las Vegas on December 30, the objective was to retrieve Smith’s parcel from the post office and collect another box he had stored at the Victory Hotel, outside of which police would arrest him and Hickock late that afternoon.

Capote’s description of the route Hickock and Smith took from Stewart Avenue to the Victory Hotel before the arrest is way out of whack: “they traveled five blocks north” — toward North Las Vegas? — “turned left, then right, drove a quarter mile more and stopped in front of a dying palm tree and a weather-wrecked sign from which all calligraphy had faded except the word ‘OOM.’”

Hickock, 28, and Smith, 31, had succeeded in eluding capture for more than six weeks since the mass murder in Kansas. Now, under arrest, they sat in separate interrogation rooms at Las Vegas police headquarters, then a few blocks west of the federal building at 400 North Main Street. Frantic agents from the Kansas Bureau of Investigation raced to Las Vegas as fast as possible to interview them. The box Smith sent to himself contained, aside from soiled clothing, pairs of black boots worn by him and Hickock — one with a distinctive cat’s paw symbol in its sole, the other with a diamond shape underneath — that the KBI believed left prints behind at the murder scene. Smith’s boot in fact had stepped in Herbert Clutter’s blood next to the body. The KBI had found Hickock’s shotgun — used in the killings — which he carelessly left propped at his parents’ home in Kansas. They also found there Hickock’s knife, used to slice Mr. Clutter’s neck.

The confessions

On January 3, 1960, the KBI agents, now in Las Vegas, switched on a tape recorder to record Hickock’s interrogation. Hickock made a lame attempt at lying. He said he met Smith in Kansas City and they planned to go to Fort Scott, Kansas, to see Smith’s sister, who had a wad of cash waiting for her brother. But they couldn’t find her. So they drove to an area frequented by prostitutes, selected two women and went with them to a motel, where after sex, the women robbed them of their money. Hickock, undeterred, also recited the many businesses where he had cashed fraudulent bank checks.

The two KBI agents interviewing Hickock told him about footprints at the murder site that appeared to match the boots owned by him and Smith. They told him about having essentially a “living witness” to the crime — Floyd Wells, Hickock’s cellmate at Kansas State Prison right after Smith got out on parole. Wells said he told Hickock about having worked for Herbert Clutter in 1948 and speculating — wrongly — that Clutter kept $10,000 in cash in an office safe at the farmhouse in Holcomb. Hickock told Wells he was determined to drive to the Clutter home, steal the cash and “leave no witnesses.” The KBI literally had no leads in the murders until Wells came forward ten days after hearing about the killings on the radio while in prison. Wells also had designs on a $1,000 reward for information on the killers offered by a newspaper.

News of a surviving witness shocked Hickock. He gave in. Weeping, he laid out a full declaration, of being there during the murders, which he pinned entirely on Smith, who he said cut Mr. Clutter’s throat and fired shotgun blasts into each family member. Hickock’s motive may have been to avoid the death penalty.

All they salvaged from the Clutter home was about $40 in cash, plus a pair of binoculars and Kenyon’s expensive Zenith transistor radio that they pawned in Mexico.

“Perry Smith killed the Clutters,” Hickock told them. “It was Perry. I couldn’t stop him. He killed them all.” He signed a document containing his written confession.

Moments later, while being led into a hallway, the still-emotional Hickock briefly lost consciousness and started to fall. Lieutenant Handlon and Clarence C. Duntz of the KBI caught the suspect and kept him from collapsing to the floor.

Under questioning by two different KBI officials, Smith would not confirm or deny Hickock’s version. After leaving Las Vegas with KBI detectives by car to Kansas on January 4 and resuming his story, Smith accused Hickock of killing Bonnie Mae and Nancy. He would even recant that tale, admitting he had killed them all, simply because he did not want Hickock’s mother to die thinking that her son was a murderer. Furthermore, Smith said that despite Hickock’s bravado, he chickened out and Smith had to kill the witnesses. He said he stopped Hickock from raping Nancy. Smith also remarked that he liked Herbert Clutter and “thought he was a very nice gentleman. Soft-spoken. I thought so right up to the moment I cut his throat.” That was before finishing him off with the shotgun.

Today, it’s still possible to trace Smith’s steps that cold winter afternoon on the front stairs leading to the old Las Vegas federal building, then enter the heavy windowed doors, walk on the original terrazzo floor and turn right to where the former postal counter is now the Mob Museum’s box office.

What’s left of the Victory Hotel — built in 1910, now closed and boarded up — still stands like an eerie monument on Main Street. The box Smith had left there, and took so much trouble to retrieve, held only a towel, and, according to KBI agent Nye, “one dirty pillow, ‘Souvenir of Honolulu’; one pink baby blanket; one pair khaki trousers; one aluminum pan with pancake turner,” some magazine pictures of male weight lifters, some medicines for swollen gums and containers of aspirin. Capote wrote that for Nye, though it provided no clues, the saved box “gave him a clearer impression of the owner and his lonely, mean life.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org