Artifact Spotlight: Alternative liquor products from Prohibition

In the 1920s liquor companies found creative ways to make products that skirted the new law

When Prohibition started on January 17, 1920, beer brewers, liquor distillers and winemakers were in a predicament. The 18th Amendment made it illegal for them to manufacture or sell their main product, so how were they going to survive?

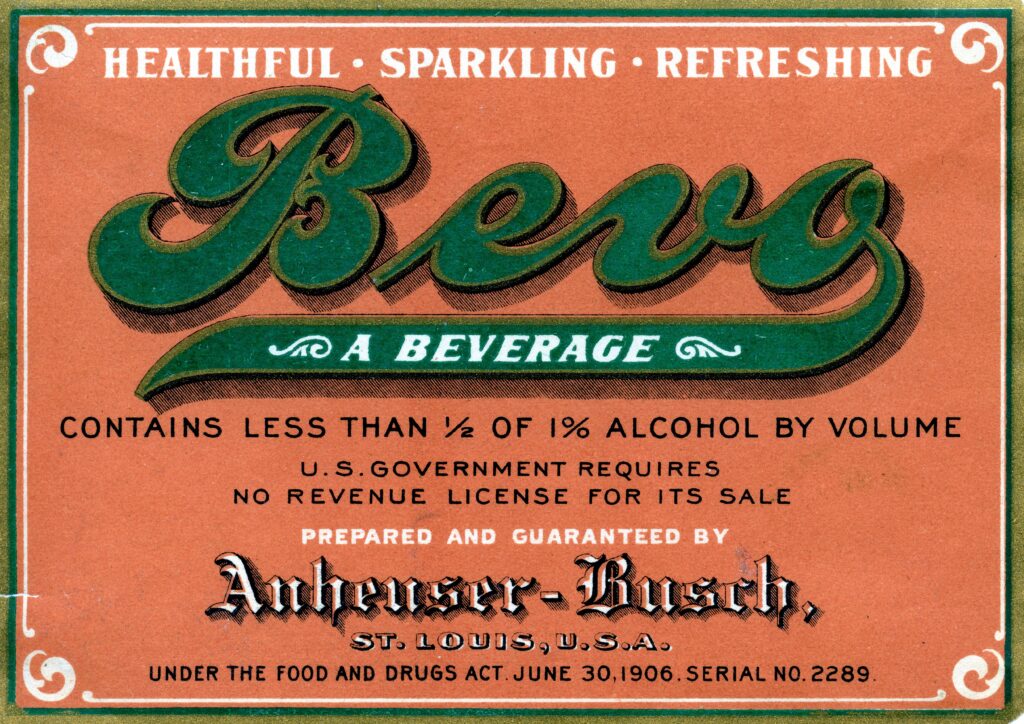

The Volstead Act, passed by Congress to enforce the 18th Amendment, defined “intoxicating liquors” as any drink with alcohol content of at least one half of 1 percent. It also outlined exemptions related to religious, medicinal and scientific uses of alcohol. While not ideal, this was something manufacturers could work with.

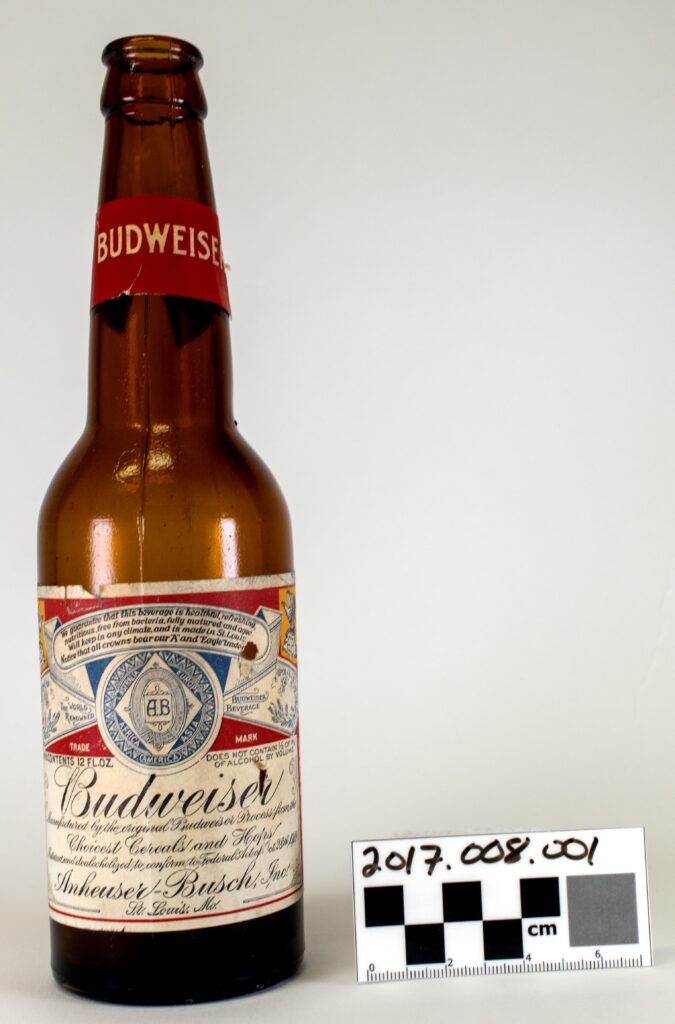

In 1916, Anheuser-Busch began producing “near beer,” a beverage that tasted like beer, foamed like beer and smelled like beer, but with the alcohol boiled off. They called it Bevo, after the Czech word for beer. At the onset of Prohibition, other companies followed suit: Miller had Vivo, Coors had Mannah and Pabst had Pablo.

Unfortunately, demand for these products plummeted as bootleggers, moonshiners and rumrunners made the genuine article widely available at neighborhood speakeasies. Without the intoxicating side effects, beer apparently lost its appeal. But brewers already had the next solution in plain sight.

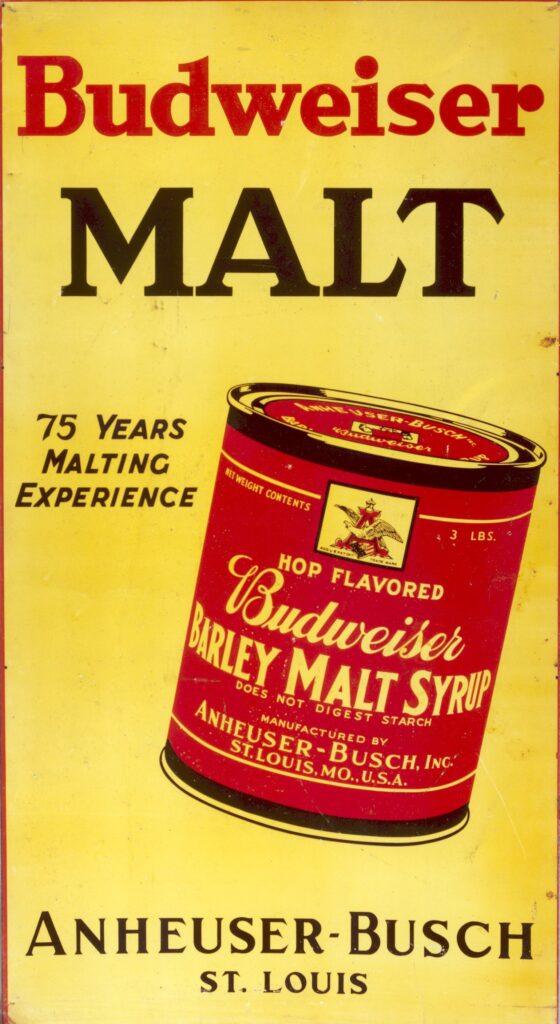

Beer doesn’t start out alcoholic. Brewers combine ingredients to make a wort, a non-alcoholic soup of hops, barley and water. Beer becomes alcoholic by adding yeast, a microscopic fungus that ferments the wort, turning sugar into alcohol. The Volstead Act only outlawed the fermented product, so beermakers could legally sell the ingredients separately.

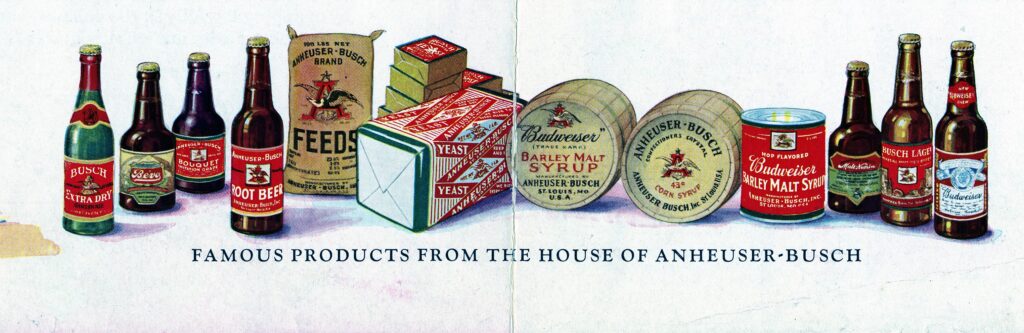

Anheuser-Busch started marketing “Hop Flavored Budweiser Barley Malt Syrup,” advertised for baking bread and making malted milk and candy. The slight sweetness of its American lager translated well into a sweetener. Coors followed its lead and effectively became a malted milk company for the duration of Prohibition. Coors continued to make malted milk until 1957.

Yet the most popular use of this product was not as a milkshake ingredient, but as a key component of the bootlegger’s supply chain. By 1926, Anheuser-Busch was comfortably weathering the storm, thanks to the hefty profits lining its coffers (from six million pounds of syrup sold annually).

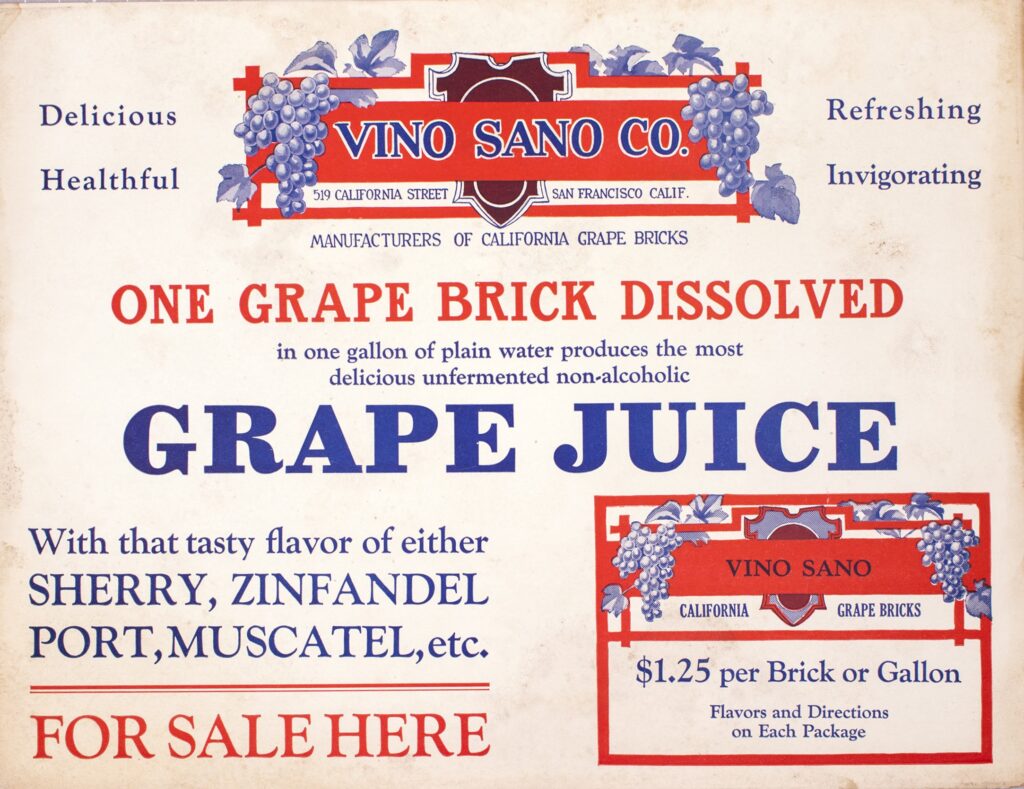

Winemakers joined brewers in the do-it-yourself market. Like beer, before the aging process starts, wine is just grape juice. To supplement income from sacramental wine, some vineyards sold bricks of grape concentrate. Consumers would add water and enjoy grape juice at home. The Vino Sano Grape Brick gave specific instructions: “To prevent fermentation add 1/10% Benzoate of Soda.” Which is to say, if you don’t add the prescribed preservative, your grape juice will eventually become wine.

Fortunately for the alcohol industry, this detour would not be the new status quo for very long. Prohibition came to an end when the 21st Amendment was ratified on December 5, 1933, ending the 18th Amendment’s 13-year crusade against alcohol. Distilleries, breweries and vineyards returned to making alcoholic beverages. Many, however, now had a slew of alternative products in their repertoire that they continued to sell well after Prohibition ended.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org