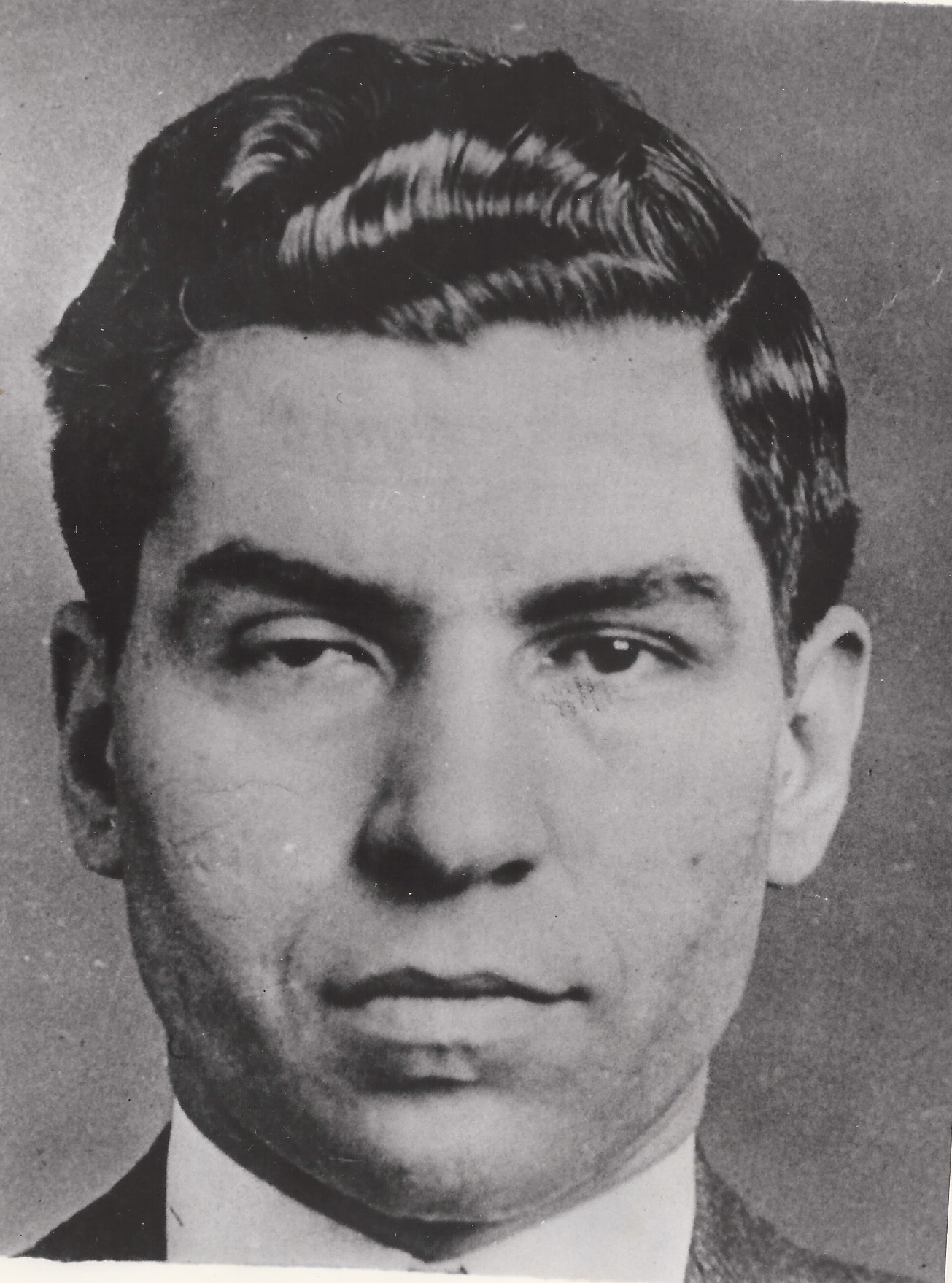

Charles Luciano survived ‘gang ride’ 95 years ago

Saved by a cop, ‘Lucky’ endured beating, stabbing

With unseasonably warm weather for a mid-October evening, Officer Henry A. Blanke dropped the convertible top of his Ford patrol car and set out from Staten Island’s Tottenville Station. He likely expected a quiet cruise down Hylan Boulevard. Blanke’s shift, however, would be anything but uneventful as the twilight hours commenced.

During the hazy purgatory between darkness and daylight, the young cop happened upon an unusual scene. A staggering silhouette appeared on a sparsely populated stretch of road near Huguenot Beach. As Blanke drove closer, he could see a disheveled figure stumbling in the beach terrain.

The officer pulled up to the individual, a battered and confused man covering much of his face with a bloodstained handkerchief. Blanke quickly scanned the immediate area for any signs of an auto accident, but there was nothing but sand and brush.

“What happened?” Blanke asked.

“I was taken for a ride,” the wounded man muttered.

Blanke discovered the mysterious man about 6 a.m. on October 17, 1929. The victim, in a bewildered state, had not identified himself yet. He asked if he was in New Jersey and presented the cop with a deal: “Get me a cab and I’ll give ya fifty bucks.” Dismissing the overture, Blanke counteroffered, “What you need is an ambulance.”

A rescue vehicle arrived and rushed the bleeding man to Richmond Memorial Hospital, where medical staff worked to stitch up and bandage the lacerations on his back, cheek, chin, neck and wrists. Detective Gustave Schley of Tottenville Station questioned the patient, who revealed himself to be “Charles Lucania.”

The detective asked him who would have committed such an assault. Lucania was largely evasive. However, he did divulge that after receiving a call from a woman to meet with him, he stood at the corner of 50th Street and 6th Avenue in Manhattan when a sedan full of assailants kidnapped him at gunpoint. The abductors put adhesive tape over his mouth and bound him. Then they threw him to the car’s floor and repeatedly beat and stabbed him. He claimed to have kicked out one of the car windows, which got him pummeled into unconsciousness. Beyond describing a few additional details, Lucania offered nothing of substance, except that he had no idea why it happened but would “take care of it himself.”

Schley ruled out robbery, because Lucania’s valuables were all intact: a gold watch, necklace and $300 tucked inside a hidden pocket sewn inside silk underwear. The patient withdrew $50 from the secret pocket. “Here’s fifty bucks,” he offered the attending doctor, “for getting your shirt all splattered with my blood.”

Detective Schley took the bandaged stranger back to the station and called Detective Thomas Tunney of Manhattan. Tunney, familiar with the 33-year-old Lucania’s reputation and history, told Schley about the suspect’s five previous arrests, a nickname (“Lucky”) and known associates, including notable gangland figures Jack “Legs” Diamond and Thomas “Fatty” Walsh (shot dead in Miami that March). Police had recently questioned Lucania about a double homicide in the Hotsy-Totsy Club speakeasy on Broadway, for which Diamond was charged, but he claimed to know nothing about it.

Considering the new information, Schley booked “Lucky” on the pretense of “protecting” him from further underworld harm. Police summarily placed him into a lineup, took his mugshot and booked him on a felony charge of automobile theft. Bail was set at $25,000.

Lucky walked out of jail, but not without the remnants of his ordeal. Though he had returned, barely, from an intended one-way trip, he was left with a drooping right eye and scarring down his cheek, neck and across the chin. The healed wounds gave him a more “sinister” appearance.

But another alteration would be of his own making. At his October 29 court appearance, Lucky, upon being addressed as “Mr. Lucania” by the presiding judge, stated he no longer went by the name because he’d grown tired of people mispronouncing it. He now wanted to be known as Charles “Luciano.”

The press latched onto the story, and versions of the “gangland ride” spread across newspapers throughout the country with cleverly penned headlines. The incident forever seared the “Lucky” moniker into underworld history, but not without an abundance of mistaken folklore and foggy conjecture to follow. Although most articles were accurate in reporting that Lucky was an established nickname (visibly written in a tattoo he acquired at age 13), all it took was one or two incorrect or misleading lines of text to kickstart the idea that he’d earned the label “Lucky” on October 17, 1929.

Over the following decades, misreporting and incorrect historical accounts created a monstrosity of the original events, which were recorded in books, magazine articles, movies and documentaries long after 1929.

The young cop who found Luciano in 1929 gave an interview to reporter Josephine Cortes in 1962. He recalled returning to the scene after taking Luciano to the hospital that day. He told the reporter he found the impressions of both male and female shoeprints in the sand, along with wire and adhesive tape. He said the police had a list of underworld suspects, many of whom ended up dead, including one “encased in cement.” He also mentioned a rumor that circulated: Luciano was friendly with a cop’s daughter at the time and allegedly had been scheduled to meet her on that fateful night.

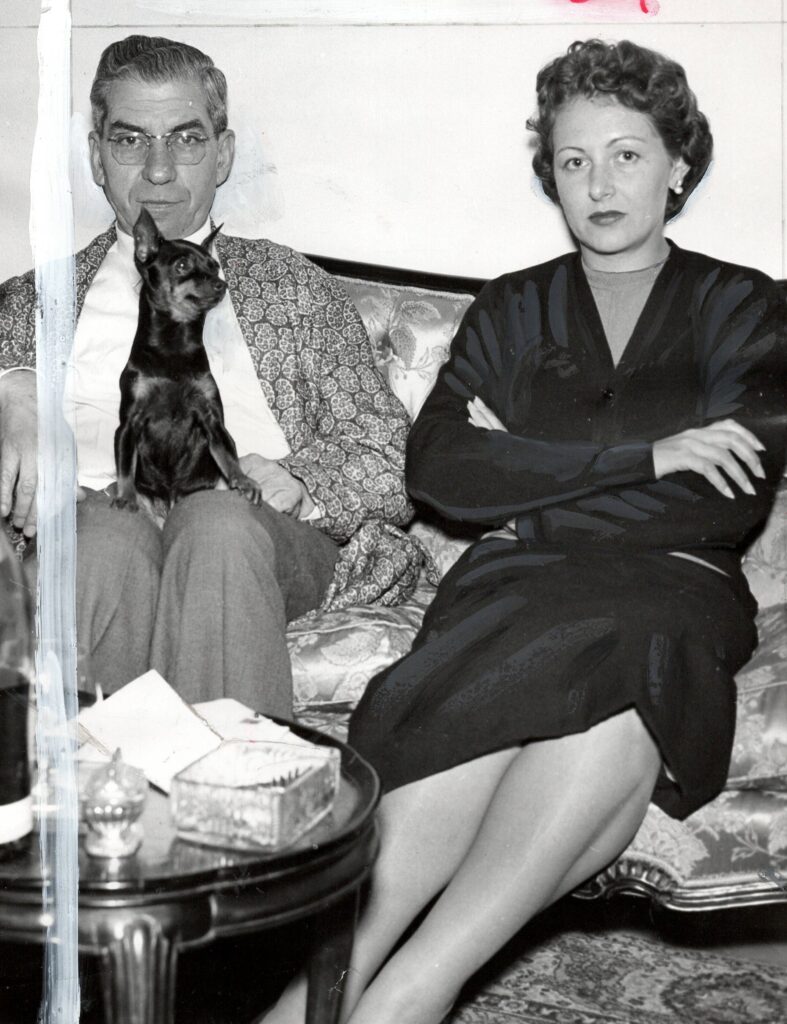

Ironically, it was Lucky who maintained the most uniformity, albeit loosely, in telling the tale. From the 1950s through his death in 1962, he began entertaining the questions of curious journalists. During an interview with sports columnist Oscar Fraley in 1960, Luciano dismissed some of the “gangland” elements of his 1929 ride. He admitted the attack was carried out because the aggressors were interested in the whereabouts of Legs Diamond, but they weren’t fellow mobsters.

“Now I know this is no gang job,” Luciano said. “They don’t put a pistol to your head and make bargains.”

According to Luciano, the kidnappers were cops — racket squad cops to be exact. He admitted to Fraley that shortly after he recovered from the assault, he put out the word that he’d “pay them back.” However, once another carload of men tried to pay him a follow-up visit, Lucky quickly issued a retraction through the grapevine: “I ain’t squealin’ on nobody, and the incident is closed.”

By the 1950s, Luciano had developed a burning desire to tell his life story, particularly in film, and entertained several propositions. Fraley claimed to be writing a script, while other would-be producers, such as Phil Tucker, threw in the towel. The team who won the deal was the duo of Barnett Glassman and Martin Gosch, though no film ever came out of it.

The infamous “ride” wasn’t the first of Lucky’s forays into police blotters, but it certainly propelled his name into the consciousness of both law enforcement and the public at large. Time magazine named him one of the “100 Persons of the Century” in 1998. As a mobster, he played cards with Al Capone, chess with Bumpy Johnson and helped restructure the underworld landscape with the likes of Meyer Lansky and Frank Costello. As a socialite, he kept company with stunning showgirls and celebrity crooners. As a poster boy for international narcotics traffic (be it real or imagined by his accusers, the jury is still out), he remained a thorn in the side of government entities, domestic and abroad, until the day he died.

On January 26, 1962, Luciano stood waiting at the Capodichino airport in Naples, Italy, for Gosch, who was reportedly interested in doing a book, not a film, on Lucky. But Luciano dropped dead of a heart attack before Gosch arrived.

Luciano’s name has since been correlated or compared to virtually every major icon of the outlaw underworld of the 20th century and into the 21st, from Pablo Escobar to John Gotti to El Chapo. His slightly disfigured face has become an iconic image of organized crime.

When reporter Llewellyn Miller visited Naples in 1952, however, the exiled mobster granted her an interview, during which she quietly observed: “The famous drooping eyelid must have been fixed by a plastic surgeon because both eyes open now to the same extent.”

Christian Cipollini is an organized crime historian and the award-winning author and creator of the comic book series LUCKY, based on the true story of Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org