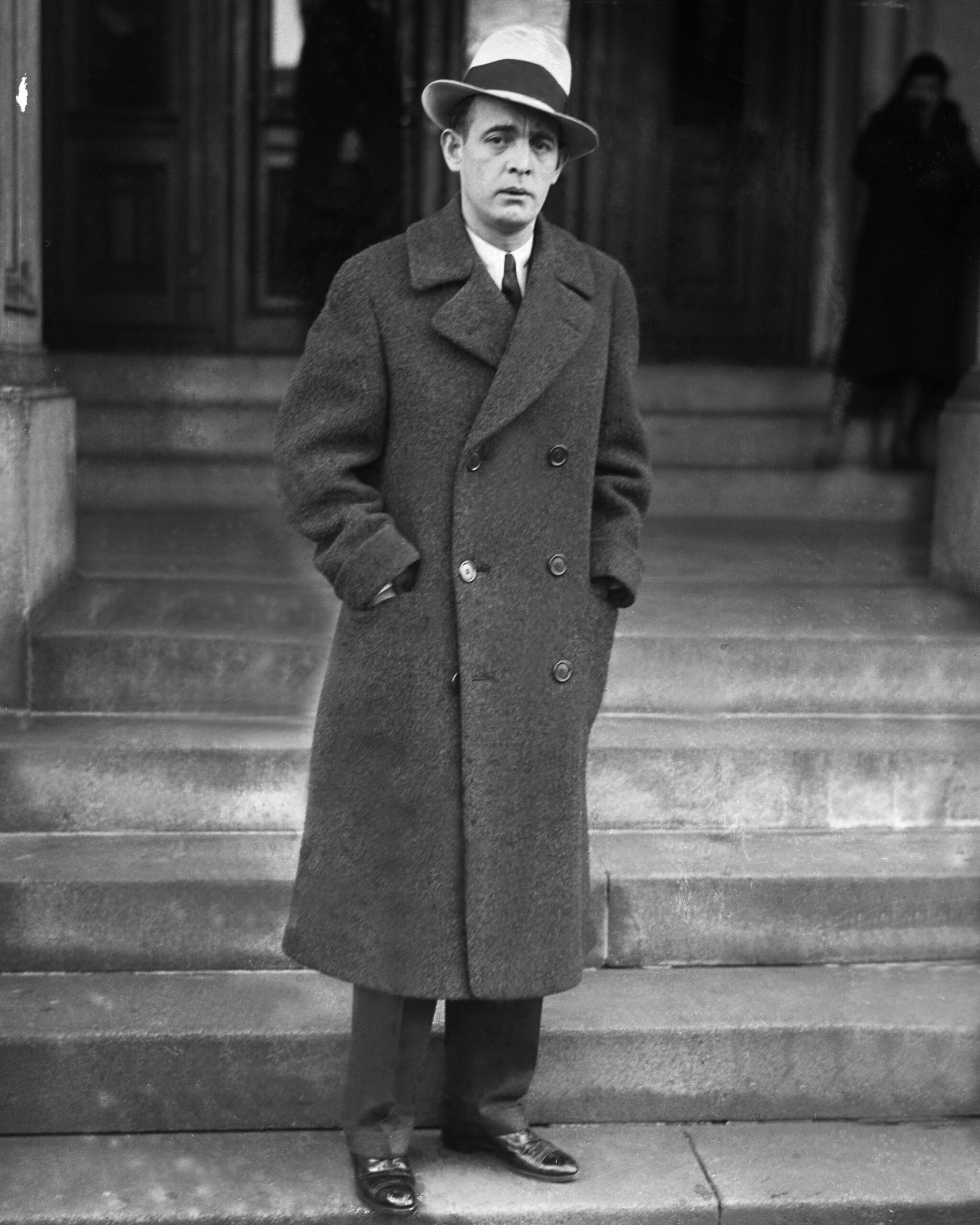

Jack ‘Legs’ Diamond: The clay pigeon of the underworld

Prohibition-era gangster survived several attempted hits until his luck ran out

A bootlegger, enforcer, dopeman and erstwhile folk hero, Jack “Legs” Diamond was like a charming archvillain in a lurid detective novel or serialized crime drama, with death-defying, law-evading cliffhangers closing each episode.

Unfortunately for Diamond, the years of partying hard, seducing showgirls and dodging bullets finally came to an end on December 18, 1931, in Albany, New York. Today, he is not a particularly well-known gangster. Which is ironic, considering his pivotal role in the larger landscape of a burgeoning new underworld structure and economy during the 1920s.

No good reason to become a criminal

Diamond was born on July 11, 1898, in Philadelphia to working-class, Irish American parents. According to biographer Patrick Downey, Legs’ formative years didn’t fit the typical profile of a future gangster. In his book Legs Diamond: Gangster, Downey writes, “He didn’t live in an overcrowded squalid tenement, nor did he have to face the problems and confines that those new arrivals from Europe had to face.” The family did, however, endure the loss of several children, and after his mother died the remaining members wound up living in a boarding house. An uncle took the kids in, says Downey, but they were soon sent to another relative who couldn’t handle the increasingly rowdy bunch. Jack found himself shipped off to New York.

Little is known about Diamond’s teenage years, except that he went to a juvenile reformatory briefly, got married and then quickly divorced. He entered the military in 1917 but went AWOL and subsequently served a prison stint at Leavenworth. Thereafter, Jack and his brother, Eddie, embarked on a life of crime. Jack soon gained influence in the New York City underworld. He met Manhattan’s contentious crime mogul Arnold Rothstein, forming a mutually beneficial business relationship that would flourish during the early 1920s.

By the mid-’20s, Diamond’s associations had grown to include a roster of notable criminals. Often found in his personal company were the boisterous fellow Irishman Fatty Walsh, a then-unknown Salvatore Lucania (Charles “Lucky” Luciano), Charles “Charlie Green” Entratta and his brother Ed. Other questionable characters in his business circles included Salvatore Arcidiaco, international con man Count Victor Lustig, and the duo of Salvatore Spitale and Irving Bitz.

Diamond gained plenty of enemies over the years, but what may have contributed to his demise was a failed mission to acquire narcotics in the summer of 1930. The State Department received a tip that Diamond was heading to Europe, but they weren’t sure which ship he boarded nor what alias he may have used. The government believed he was traveling with others: Entratta, Lucania, Arcidiaco and someone known as Traeger. While customs agents, police and the press agencies pursued Diamond from Ireland to France, his companions evidently slipped into the shadows of Antwerp, Belgium. From there they spread out, purportedly to carry out the mission without him. Diamond’s trip finally ended when German authorities detained him as an “undesirable” and shipped him back to Philadelphia empty-handed.

The ‘clay pigeon’

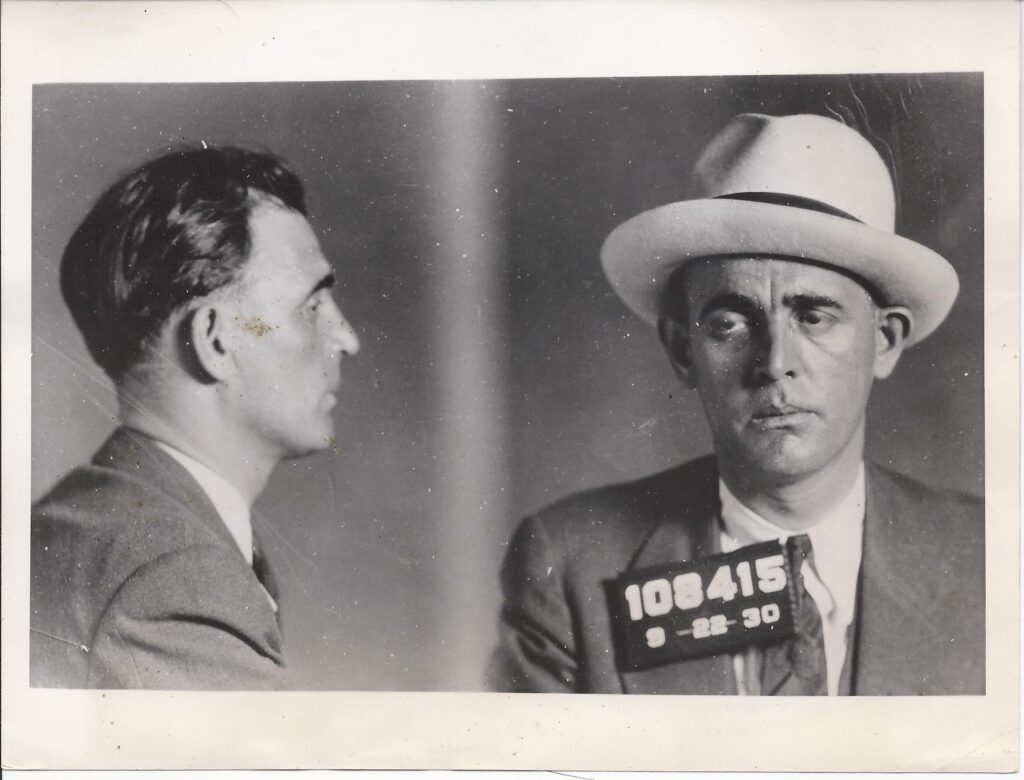

During his criminal career Diamond accumulated more than 20 arrests, but he walked away mostly unscathed each time. His reputation made him a usual suspect in many sensational and scandalous crimes of the 1920s. He was accused in some of the most shocking underworld homicide cases, including the murders of Rothstein in 1928, Fatty Walsh in 1929 and a 1929 double murder inside the Hotsy-Totsy nightclub.

The charges didn’t stick, and bullets often proved ineffective. From 1924 to 1931, Legs miraculously survived four assaults, altogether shot with more than 70 buckshot pellets and nearly a dozen pistol slugs. The assassination attempts only brought him more heat. “Every time I get shot, they arrest me instead of looking for the guy who shot me,” Diamond said in July 1931.

Legs probably knew he lived on borrowed time. John O’Donnell of the New York Daily News, one of the few reporters Diamond liked, struck a deal with him in the spring of 1931 that would serve to divulge some truths, offer a positive spin and hopefully save some face for Legs. Marion “Kiki” Roberts, Jack’s Ziegfeld Follies mistress, had been indicted along with him and others for involvement in a kidnapping and torture. Legs was acquitted but knew Roberts, who had been avoiding the police, would eventually have to surrender herself. O’Donnell offered to escort her and have the paper cover her legal costs, if in return, she and Jack would give interviews. Legs agreed with one caveat: “When I’m dead,” he told O’Donnell, “you can print this stuff.”

The last drink

On December 18, 1931, Diamond and his wife, Alice, celebrated yet another acquittal on that fateful night. After becoming quite inebriated, he took a cab from a roadhouse back to the boarding house, alone.

Minutes after he fell into a drunken slumber, assassins entered his bedroom and shot him. He died instantly. There was no glamorous last stand, no dramatic throes of death. He never saw it coming.

The boarding house proprietor was the first person to discover the blood-soaked aftermath and promptly called the club to alert Diamond’s wife, who raced to the scene. The police were phoned next. Authorities arrived on scene to find Alice in an inconsolable state, cradling Jack’s head in her arms, repeating the phrase, “I didn’t do it.”

According to the proprietor, two men exited the building and drove off in a burgundy sedan bearing Brooklyn license plates. One perpetrator carried a flashlight and the other a revolver. Later, a .38 revolver and flashlight, wrapped in silk, were recovered from the lawn of St. Paul’s Church barely a mile from the crime scene.

Diamond’s body was delivered to the morgue where the coroner established that three shots were fired at close range, aimed just below his left ear. Two of those bullets lodged in Diamond’s head, and the third round passed entirely through his neck.

Diamond’s death garnered no sympathy from law enforcement. “So they got him at last!” said New York City Police Commissioner Edward P. Mulrooney. “It’s no loss to the community — not this community anyhow.”

Theories still circulate around the circumstances of Diamond’s death, but one of the most plausible goes back to the failed mission in Europe. On October 12, 1930, shortly after his deportation from Germany, Diamond survived an attempted hit at the Monticello Hotel in Manhattan. Details about the trip began to trickle out shortly thereafter. Salvatore Arcidiaco and Count Lustig, both under questioning, admitted they were, in fact, on the Europe trip. The former dismissively said it was just a liquor deal, but letters found at Diamond’s residence seemed to corroborate suspicions of a narcotics deal, not booze. After Diamond’s death in 1931, rumors surfaced that Salvatore Spitale and Irving Bitz had given Diamond more than $200,000 to secure a drug deal. Diamond came back with no money and no drugs, which may have sealed his fate.

Diamond’s mistress, Kiki Roberts, capitalized on the publicity for a short time before drifting into obscurity. His wife, Alice, tried to cash in on Diamond’s notoriety, but she too fell on hard times. She became involved with some questionable characters, and in June 1933 was found dead in her apartment from a gunshot wound to the head. Just like Jack’s murder, nobody knows for certain who killed Alice.

The Albany boarding house at 67 Dove Street, where Diamond was murdered, still stands and is now a townhouse. It was sold in November 2023 for $375,000.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org