The fall of Salvatore Maranzano, and the rise of the new Mafia

Lucky Luciano and his co-conspirators clear the path for a bolder brand of organized crime

The autocratic reign of self-proclaimed boss of all bosses Salvatore Maranzano came to a bloody end 92 years ago this month.

A progressive faction of underworld gangsters were setting the stage for a violent preemptive strike against the last of two warring criminal overlords. The young turks had already successfully deposed Giuseppe Masseria in April. It was an inside job carried out by members of his inner circle.

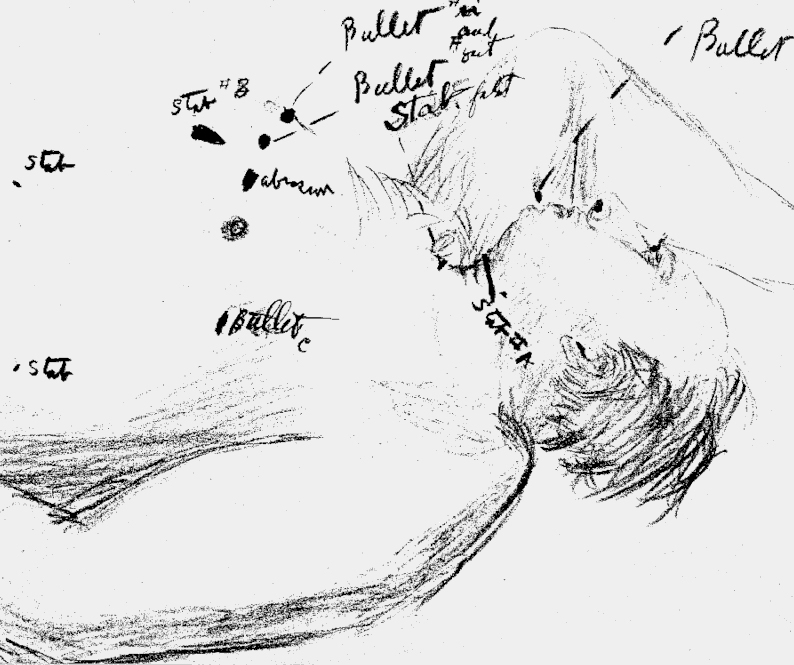

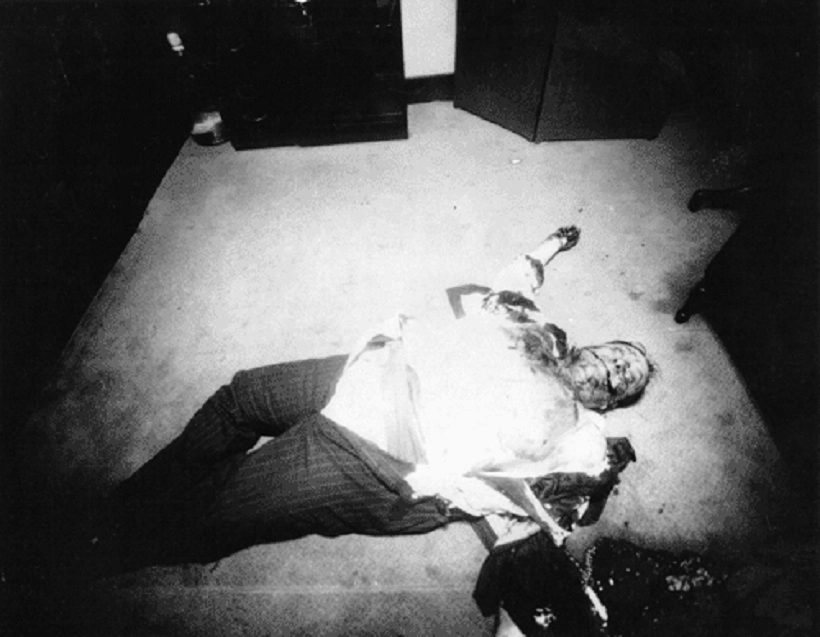

Maranzano also had to be dealt with, but the plot took time and careful planning. Maranzano suspected his new minions might contemplate a coup against him, and thus laid down secret plans of his own. But before he could execute the plan, his enemies struck first. On the afternoon of September 10, 1931, a group of between four and six men (witness and informant accounts vary) entered the office building at 230 Park Avenue in Manhattan. They ascended to the ninth-floor office suite of Eagle Building Corporation, the Maranzano headquarters. The assassins entered the waiting area, brandished badges to the secretary, and forced the nine other waiting room guests against a wall. Upon entering Maranzano’s office, a melee ensued. Maranzano’s throat was slashed and his body riddled with bullets. The killers raced to the stairwell and into the history books of great gangland mysteries.

The backstory

Salvatore Maranzano emigrated from the Castellamare del Golfo region of Sicily, settling first in Buffalo, New York, sometime around 1925. He had already been aligned with other Castellammarese Mafiosi living in New York and had every intention of expanding his own power over the Mafia-controlled rackets. By the latter 1920s, he had moved his wife and children to Brooklyn, set up an office in Manhattan and earned a reputation as a Mob power player, particularly in the bootlegging business.

However, that was merely the beginning, because Maranzano had been executing plans to extend his reach into a realm long held by Manhattan’s other big boss, Giuseppe Masseria. Joe the Boss, as he was known around the city, enjoyed a reputation of being both loved and hated, and also earned references to being New York’s version of Chicago’s Al Capone. In fact, Masseria and Capone were in alliance, which isn’t surprising for numerous reasons, including having particular men in the former’s ranks. Some of Joe the Boss’s strongarms, bodyguards and confidants were old friends of Capone dating back to their teen years, Lucky Luciano and Frank Costello among them.

Masseria, probably believing his alliances were broad and strong enough to quickly put Maranzano in his place, instigated what would later come to be known as the Castellammarese War. Masseria, however, proved to be the weaker, and his own men began defecting. Some even conspired to kill him. Masseria dined on bullets on April 15, 1931, in a Coney Island restaurant. Maranzano welcomed the plotters into his domain, but never completely trusted them.

The social network

The common denominator between Masseria and Maranzano was an outdated and narrow-minded business philosophy that nearly all their underlings despised. Men of that old-fashioned mindset were quietly referred to as “Moustache Petes” by their younger, forward-thinking subordinates. Such ideology would prove to be the downfall of both egomaniacal bosses. Both assassinations were successful largely because of the organizers’ incredible networking skills. It’s fascinating to think of how coordinated the plotters were in an era long before social media and one in which even neighboring police forces didn’t have the tools or processes for effective information sharing. From Luciano to Capone to Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, virtually everyone who was anyone among the new generation of gangsters was aware of plots or directly in on the hits.

The immediate reaction to Maranzano’s murder, especially from federal authorities, was to focus on a purported alien-smuggling racket. A reporter discovered one of Maranzano’s address books outside the office building, leading investigators to theorize it was thrown out a window or dropped by one of the killers. The “little black book,” as it was dubbed, contained 30 to 50 names, some of whom were prominent figures, including judges and immigration officials. Other theories pointed to a narcotics ring, a Capone link (because two of the assassin’s hats were recovered and bore Chicago labels), and/or a liquor squabble.

In similar fashion to the investigation of Masseria’s murder, Luciano remained largely under the radar, except for a brief but critical mention by New York’s contentious and unfiltered police commissioner, Lewis J. Valentine. The day after Maranzano’s death, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle printed an article that paraphrased the commissioner’s comments. Valentine told reporters that while likely rooted in an alien-smuggling or narcotics ring, those were merely still theories. He went on to say police weren’t sure if it was “Lucky Lucciano” [sic] or Maranzano who succeeded the dead Masseria, but they certainly believed a rivalry between the two was apparent. Another report by the paper added:

“Despite the fact that Lucciano [sic] won out, Maranzano, according to Mulrooney, was one of the organizers of a three-day fiesta staged in Coney Island Aug. 1, 2 and 3 to install Lucciano [sic] in proper style.”

As more details of Maranzano’s murder were revealed, the consensus among authorities and the news media was that further gang rubouts were likely. Indeed, their premonition was correct, but was it as grand as the legend claims?

Night of the Vespers

In a passage from the translated memoirs of Nicola “Zu Cola” Gentile, obtained by federal agents, he wrote:

“They hurried to telephones and informed the boys in various parts of New York advising them that they could start the purging operation. Almost immediately with that word there took place the slaughter of the ‘Sicilian Vespers.’ In fact, many of the followers of Maranzano were killed, who were stained with the most atrocious wickedness.”

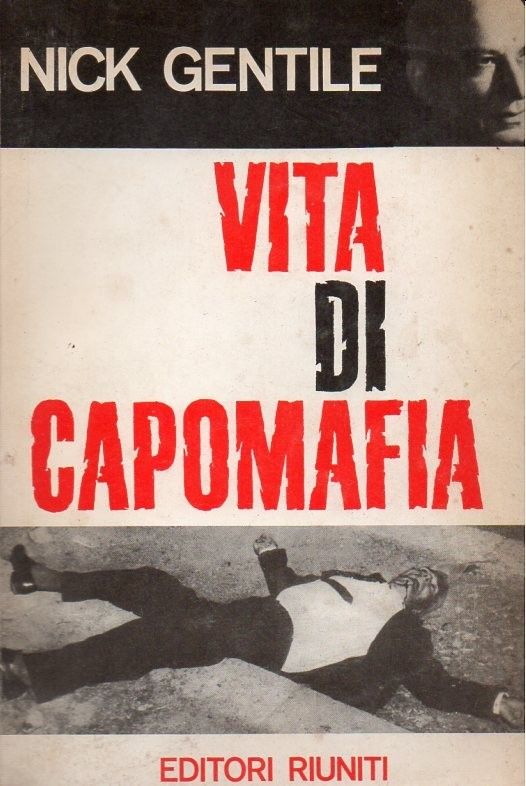

The story of Maranzano’s murder and the subsequent elimination of his followers got spun into folklore over time via the accounts of four main storytellers: Dixie Davis (former Dutch Schultz attorney), Nicola Gentile, Joe Valachi and Joe Bonnano. Each of these four offered varying degrees of authenticity and corroboration, with Gentile’s account being the most widely accepted. Gentile’s memoir was discovered by (or directly given to) narcotics agents sometime between 1940 and 1960. The translation of these memoirs provided a particularly poetic passage referencing “Sicilian Vespers.” The book version, Vita di Capomafia, released in 1963 by Gentile and editor Felice Chilanti, varied somewhat from the early translated notes, forgoing the melodramatic wording (notably the omission of colorful phrasing such as “Sicilian Vespers”), but essentially kept the core material intact.

The identity of those on the actual hit squad is a subject of speculation, though it’s understood the entourage was comprised of Jewish gangsters, possibly accompanied by one Italian who could positively identify Maranzano. It’s believed Samuel “Red” Levine led the hit squad. Abraham “Bo” Weinberg claimed he was there as well.

Weinberg’s account also placed Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll at the scene but not as a killer of Maranzano. Coll was allegedly entering the building as the slayers were exiting. Coll was hired by Maranzano to kill Luciano and Vito Genovese, both of whom were scheduled to meet with Maranzano that fateful day. Again to the point of social networking, another account of the plot points to Maranzano underling Tommy Lucchese being the double agent who informed Luciano of Maranzano’s “hit list,” which included the names of Luciano, Costello, Schultz, Capone and more. Armed with that information, Luciano and Genovese knew the scheduled meeting would probably be their demise and thus quickly enacted an already-planned coup.

Because Maranzano would likely be on guard within the presence of his own men, let alone any familiar and/or suspicious-looking Italians, the plotters turned to a Jewish faction led by Meyer Lansky and Ben Siegel. Maranzano wouldn’t easily recognize the selected team of Jewish assassins. Although it’s possible Siegel participated in the hit (as dramatized in the recent Lansky movie), it is unlikely. Siegel was probably too well known or recognizable, therefore he probably limited himself to the planning and post-murder phases.

The murder of Maranzano was not the end of the violence, but rather the beginning of a fabled purge to rid the underworld of hardcore Maranzano loyalists and other Moustache Petes, both in and outside New York. Historians disagree on whether a literal purge ensued or not, though generally are in agreement that other murders took place that year and into the next that could have been related.

Nicola Gentile’s memoir did not offer many specific details beyond his role in immediately traveling to Pittsburgh to assassinate Maranzano ally Giuseppe Siragusa. Dixie Davis relayed the account of Bo Weinberg in a 1939 magazine column, whereby the number of dead reached 90. In the article, Davis expressed some doubt about the high number, but concurred a lot of “greasers” got killed.

Joe Valachi, during his sensational Senate committee testimony in 1963, never stated a specific number of casualties. Murder Inc. prosecutor Burton Turkus (with writer Sid Feder) stated in the book Murder Inc. that “some 30 to 40 leaders of Mafia’s older group all over the United States were murdered that day and in the next forty-eight hours!” Decades later Attorney General Ramsey Clark addressed the subject in his book, placing the number of dead at 40. Most of these estimates and claims were not accompanied by any solid data or supporting evidence. An alternative theory to the so-called purge: It may be more of an abstract, a culmination of all the Mob hits dating back to the Castellammarese War and including the victims associated with Masseria’s downfall.

Parting shots

Maranzano’s murder remains unsolved and left a legacy of other mysteries as well. Besides the question of a so-called purge, perhaps the most inconclusive element involves Maranzano himself, specifically photos. While it’s true some infamous or camera-shy mobsters left us few visual artifacts, Maranzano left none, as in, we don’t know what he looked like beyond the handful of post-mortem crime scene photos.

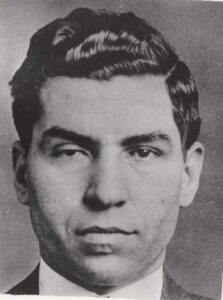

There is a portrait of a living Maranzano that’s been circulating for decades, but it’s not him. David Critchley’s article in the July 2009 issue of Informer Journal revealed that the widely accepted photo of Maranzano was actually that of a British criminal named Salvatore Messina. Then, in 2019, a discovery by another researcher uncovered a photo believed to be the real Maranzano. But shortly thereafter, the photo was deemed a case of mistaken identity. The photo was actually German mass murderer Peter Kurten.

Christian Cipollini is the author of Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad and LUCKY, a gangster graphic novel.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org