Nevada marks 90th anniversary of legal gambling

Mobsters played critical role in growth of Silver State’s dominant industry

Ninety years ago today, Nevada legalized gambling. It changed everything — eventually.

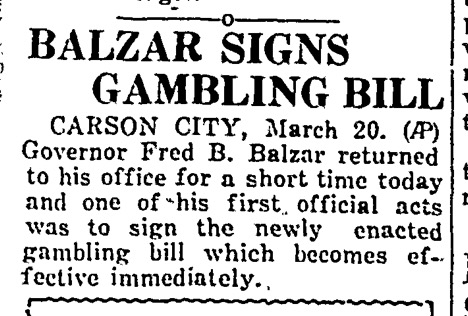

When Governor Fred Balzar signed Assembly Bill 98 on March 19, 1931, few Nevadans could have foreseen the long-term significance of what had occurred. The Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal surely didn’t, as news of the bill signing earned one short paragraph at the bottom of the front page the following day.

By contrast, United Press International correspondent Earl H. Leif had an inkling the legislation could have historic importance:

“The lid is off now, the sky is the limit, and investors can feel safe to place their money here in high-class gambling casinos, and there may be keen rivalry between Las Vegas and Reno for the title of the ‘Monte Carlo of America.’”

No doubt responding to Leif’s exuberant prognostications, the Review-Journal, in a March 21 editorial, sought to temper its readers’ expectations:

“People should not get overly excited over the effects of the new gambling bill — conditions will be very little different than they are at the present time, except that some things will be done openly that have previously been done in secret. The same resorts will do business in the same way, only somewhat more liberally and above-board.”

The newspaper’s killjoy prediction proved to be more accurate in the short run. The transformation of Las Vegas from dusty railroad town to American Monte Carlo was delayed, at least in part, by the Great Depression. While Las Vegas was doing better economically than many other communities across the country thanks to Hoover Dam construction, the banks that hadn’t gone under were not exactly handing out loans to build bigger betting palaces, especially considering that gambling was still considered a sin in wide swaths of the country.

Even in Las Vegas, there was some reluctance to fully embrace gambling. The first city ordinance outlining casino licensing fees and regulations required that “all glass doors to gambling establishments and abutting on streets or alleys must be opaque or curtained to shield the interior from view by passers-by,” according to the Review-Journal.

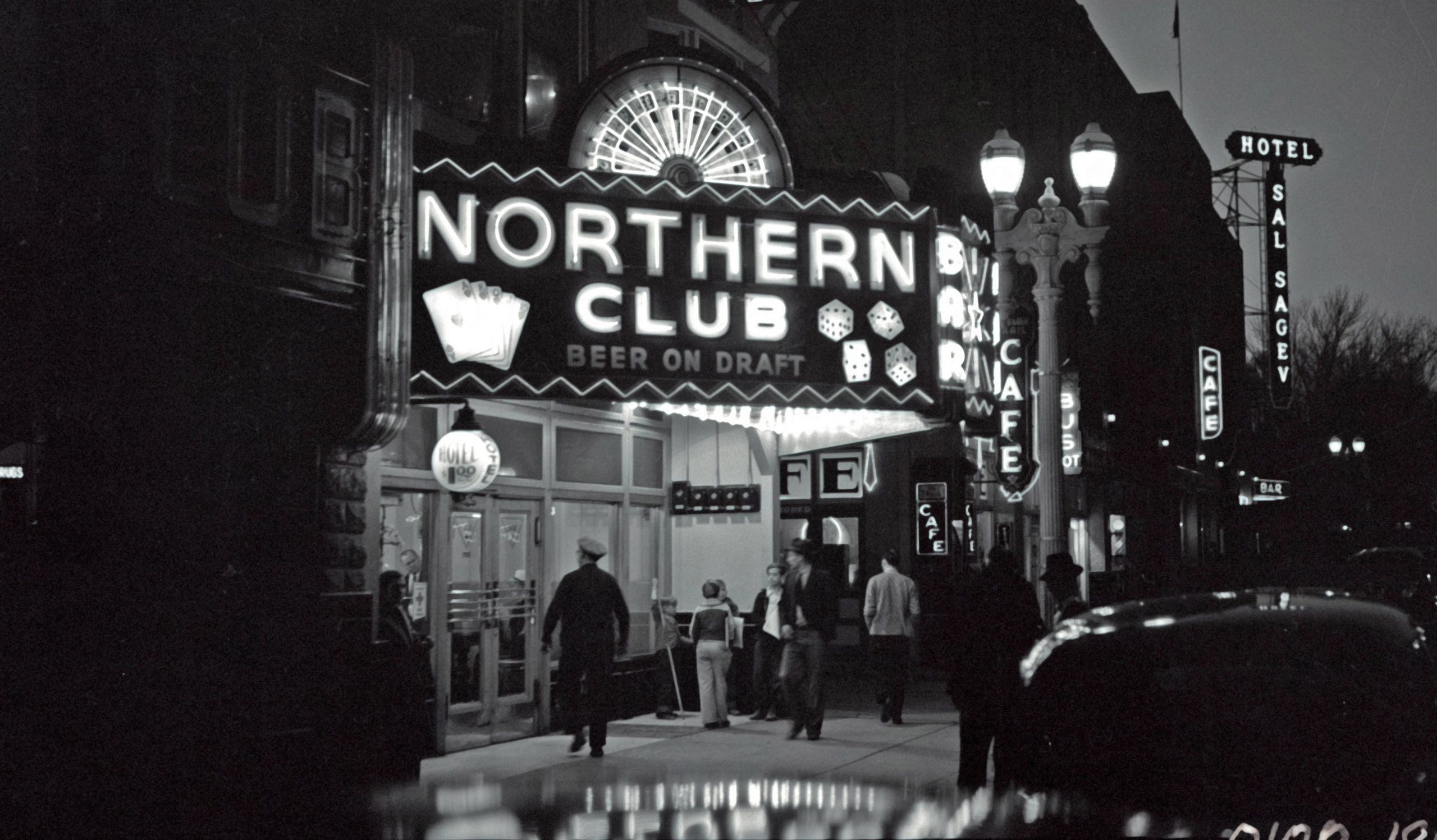

On April 2, 1931 — 12 days after the state legalized gambling — the Clark County Commission granted licenses to eight businesses: the Northern Club, Las Vegas Club, Boulder Club, Red Rooster nightclub, Big Four Club, Exchange Club, Rainbow Club and Meadows Casino.

Most of the licensed casinos crowded along the west end of Fremont Street. There was no vision, in those early days, that the city could attract millions of tourists by building casino resorts with showrooms, buffets, swimming pools and horse stables. That discovery would come a decade later.

Rise of the Strip

The incremental growth of the Las Vegas casino industry during the Great Depression took a dramatic turn starting in 1941. Eighty years ago this spring, Las Vegas transformed from a town to a city, from a regional curiosity to an international resort destination.

Three major developments in 1941 kicked off an unprecedented growth boom. The first of these was the construction of an Army air field.

The United States did not formally join the fight against the Axis Powers until after Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. But America contributed money and materials to the Allies as early as 1940. And, figuring it was just a matter of time before we became directly involved, the military was getting ready.

In October 1940, Army Air Corps officials scouted several Southwestern desert locations for an aerial gunnery school. Las Vegas was selected because it offered large, uninhabited areas north of town, the ability to train year-round, and an inland location that reduced the likelihood of an enemy attack.

The Army began construction in March 1941. The first commanding officer, Colonel Martinus Stenseth, had his first office in the basement of the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse at 300 Stewart Avenue – the building that today houses The Mob Museum. From this temporary base of operations, Stenseth and his junior officers designed the gunnery school curriculum.

Since the base had to be constructed from scratch, it was a massive endeavor. Besides the runways, crews built 173 buildings and installed electrical lines, sewer and water systems, and the technical equipment needed for a cutting-edge military operation.

By July 1941, more than 800 enlisted men were stationed at the base, moving into the newly constructed barracks and helping to build other structures. After Pearl Harbor, the Las Vegas Army Air Field expanded dramatically. In 1942, its first full year in operation, the airfield graduated 9,117 gunners.

At its peak in 1943 and ’44, the airfield hosted more than 15,000 enlisted men and women, all of whom spent money in area stores, restaurants, theaters, bars and casinos. Senior enlisted men were allowed to live off the base with their wives, creating a pressing demand for housing. Today, that training facility is known as Nellis Air Force Base.

While the Army airfield sprouted northeast of Las Vegas, another war-related project was gearing up to the southeast. Basic Magnesium Incorporated was created to produce magnesium, a lightweight metal that, when incorporated into the structure of aircraft, increased their speed and maneuverability. Magnesium also was used in bombs, flares and tracer bullets.

The man behind the magnesium plan was Howard Eells of Cleveland. In 1936, Eells discovered rich magnesite deposits in northern Nye County. He originally wanted the magnesite to produce furnace bricks, but as war raged in Europe, he recognized the value of his discovery to America’s military.

Eells partnered with a British company to build the plant. The U.S. government invested $130 million in the project. Eells decided to locate the facility about 20 miles southeast of Las Vegas. Why there? It was close to Hoover Dam, which could provide abundant water and electricity, and not too far from Las Vegas, which had the railroad.

Construction started in September 1941. By December, more than 2,700 men were working there. The numbers soon soared, reaching a peak of 13,000 in 1942. The magnesium plant was the foundation for the city of Henderson.

The third major development was the El Rancho Vegas, which opened on April 3, 1941. It was the first hotel-casino on what eventually came to be called the Las Vegas Strip. The Western-themed resort debuted with 50 rooms, restaurants, a theater, a casino and a swimming pool.

According to a popular legend, in 1940 a California hotel builder named Thomas Hull and a friend were driving on Highway 91 toward Los Angeles when their car got a flat tire just south of the Las Vegas city limits. While the friend hitchhiked back to town to seek assistance, Hull waited beside the highway and counted the cars going by. After an hour of this, he became convinced he had found a great spot to build a hotel.

That’s a clever origin story, but it bears little resemblance to what really happened. In fact, Hull first expressed interest in building a Las Vegas hotel as early as 1938. Las Vegas business leaders Robert Griffith and Jim Cashman encouraged Hull to make the investment.

However, Hull did not secure financing for the venture until 1940 — in other words, not until news of the soon-arriving Army Air Field and magnesium plant surfaced.

Hull chose not to build within the city limits. Instead, he bought an affordable piece of land on Highway 91 south of San Francisco Street (now Sahara Avenue), just outside the city boundary. There, he was not subject to city taxes or regulations.

Wesley Stout, a writer for the Saturday Evening Post magazine, showed up in Las Vegas in 1942 and wrote an article about what was happening here. The article, titled “Nevada’s New Reno,”offered an interesting take on what the Las Vegas boom meant:

“There are bigger war booms than Vegas’, but not relatively, nor any other as gaudy. There’s never been anything quite like it, and there may never be again. The population has more than doubled, exclusive of two Army camps. For the first time in Nevada, Reno and Washoe County have been shoved back into second place.”

In a matter of a year or so, Las Vegas had surpassed Reno to become the state’s premier vacation destination.

Enter the Mob

Before the 1940s, Las Vegas saw its share of thieves, schemers, killers and other ne’er-do-wells. Gunplay and robberies were not unusual in Block 16, the city’s red-light district. Bootlegger Jim Ferguson was dubbed the “King of the Tenderloin” in Las Vegas in the 1920s. But the traditional Mob took little interest in the small desert town until it became a fast-growing city.

Individual mobsters started hanging around Las Vegas as early as 1941, but the syndicate’s first significant business play was the acquisition of the El Cortez hotel-casino on Fremont Street in 1945. Meyer Lansky, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, Moe Sedway and Gus Greenbaum were among the investors. But they ran the El Cortez for less than a year before selling out, because a bigger opportunity had entered their radar.

The origins of the Flamingo Hotel are no longer in dispute, but unfortunately many people still buy into the myth, so let’s briefly set the record straight once more. The original developer of the Flamingo was not Bugsy Siegel, it was a Los Angeles newspaper publisher and nightclub operator named Billy Wilkerson.

Wilkerson’s project started with the purchase of the land on which the Flamingo would stand. In March 1945, Wilkerson wrote a check for $9,500 to Margaret Folsom. This was a down payment for 33 acres on the east side of Highway 91 south of Las Vegas. He paid Folsom a total of $84,000 for the property. The Mob Museum has in its collection Wilkerson’s original down payment check.

Wilkerson started building the Flamingo in 1945 but ran out of money. Wilkerson was a problem gambler – he lost hundreds of thousands of dollars at the green-felt tables, money that could have been spent to build the Flamingo. Lacking options, Wilkerson turned to Meyer Lansky and his underworld associates to invest in and help him finish the Flamingo.

Lansky needed someone to keep an eye on their investment. Siegel, who lived in Los Angeles and had other business interests in Las Vegas, was the logical choice. Siegel started spending time on the construction site, and before long he wanted more control over the project. He and Wilkerson did not see eye to eye on how things should be done, and Wilkerson was pushed out.

Siegel was now in charge, and he spent millions more than Wilkerson had planned to make the Flamingo a modern, elegant resort. Siegel procured additional funds from his co-investors, but he faced pressure to start showing some returns on their investments.

He opened the Flamingo on December 26, 1946. It turned out to be a bad move, because the hotel rooms were not finished, and guests who might have enjoyed a couple of hours at the Flamingo had to leave to sleep at competing resorts. The Flamingo lost money, and Siegel decided to shut it down until the rooms were finished.

When the Flamingo reopened in the spring of 1947, it did much better, but Siegel’s tenure at the helm was cut short on June 20, 1947, when an assassin shot him to death in Beverly Hills, California. The case was never solved, but the conventional wisdom is that his syndicate friends saw a smoother and more prosperous future without Bugsy running the Flamingo.

The El Cortez and Flamingo were just the beginning of the Mob’s infiltration of the Las Vegas casino industry. Crime families had hidden — and sometimes not-so-hidden — interests in more than a dozen casinos that sprouted along the Strip in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. The Mob’s efforts to grow the industry were fueled in large part by low-interest loans provided by Jimmy Hoffa, who led the Teamsters Union and controlled its Central States Pension Fund.

The Mob’s heyday in Las Vegas ran from 1945 to about 1975. After that, state gaming regulators and federal agents became more aggressive in ferreting out casino skimming schemes, forcing the Mob to look for the exits.

Entrepreneurs and corporations soon took control of the Strip. With greater access to capital, they built megaresorts – sprawling hotels with thousands of rooms and numerous amenities, from luxury restaurants and giant showrooms to retail shops and convention halls.

Las Vegas today

When the coronavirus started spreading across the United States in early March of 2020, Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak ordered the state’s casinos to shut down for 11 weeks. It was the first time anything like this had happened in nine decades of legal gambling. Casinos that had operated 24/7/365 for years started searching for the keys to doors that had rarely been locked.

Now, as widespread vaccinations give hope that the end of the pandemic approaches, Las Vegas tourism officials are gearing up for a resurgence of visitors. Legal gambling’s 90th anniversary coincides with big plans for entertainment venues to reopen, conventions to return, and 65,000-seat Allegiant Stadium to fill with Las Vegas Raiders fans. The 3,500-room Resorts World will debut this summer, filling a void on the north Strip, while downtown’s Circa, which brazenly opened in the midst of the pandemic, will finally see its full potential realized.

The Las Vegas casino industry in 2021 bears little resemblance to the handful of small gambling parlors that lined Fremont Street in 1931. But Las Vegas would not be what it is today were it not for the Nevada legislators who assembled in Carson City and audaciously voted to legalize gambling 90 years ago.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org