Embattled ‘maxi-trial’ prosecutor takes on ’Ndrangheta

Upcoming television series and book add to Mob courtroom drama underway in Italy

Nicola Gratteri has not been to a restaurant in 20 years. The 62-year-old lawyer eats in his office. His home, he says, is a bunker. Armored vehicles and armed guards have been a part of his life for decades, since he began taking on the ’Ndrangheta crime syndicate in southern Italy.

His lifestyle won’t change anytime soon. Since January, Gratteri has been chief prosecutor in the “maxi-trial” underway in Calabria, a rugged region at the toe of Italy’s boot near Sicily. Calabria is considered the ’Ndrangheta’s home base.

The trial is one of the largest in Italian organized crime history, with 355 defendants reputedly linked to the ’Ndrangheta. A pre-trial hearing lasted about three hours as the defendants’ names were read, some with nicknames such as “Fatty,” “Blondie” and “Little Goat.”

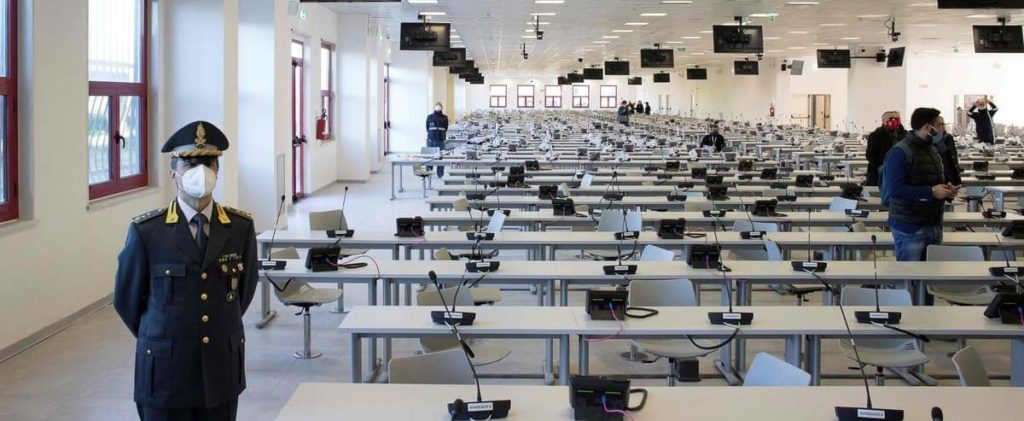

The defendants are charged with an array of serious crimes, including murder, drug trafficking and loan sharking. Public officials and police officers are among those charged. The trial is expected to last two years. It is being conducted in a large call center converted into a courtroom. Security is tight, with COVID-19 restrictions in place.

Deadly drama

The Wall Street Journal has referred to the ’Ndrangheta as the Western world’s richest crime syndicate. The syndicate is thought to control 80 percent of the cocaine trade in Europe, generating an annual income of $64 billion. According to The Atlantic, the term ’Ndrangheta, pronounced en-drahn-get-ta, comes from the Greek andragathía, meaning “man of honor” or “heroism.”

Calabria is an impoverished, violent region with a history of intertwined relationships, sometimes involving family and friends in opposing camps. These complicated relationships are part of the drama unfolding in this massive court case and in other legal battles involving the ’Ndrangheta.

Gratteri is among those whose relationships are part of the Mob-fighting story in Italy. A shopkeeper’s son, he grew up in the small Calabrian town of Gerace, where he played barefoot soccer with some of those he has gone after over the years.

This continuing deadly drama, dating back generations, is played out in more places than courtrooms. An upcoming television series and soon-to-be-published book are recent examples of how the public’s interest in Italian organized crime remains high.

According to a report this month from Deadline, a six-part series titled The Good Mothers has been commissioned byDisney+ and its international streaming service, Star. Based on journalist Alex Perry’s 2018 nonfiction book of the same name, the series will focus on three women inside the ‘Ndrangheta as they work with prosecutor Alessandra Cerreti to take on the syndicate.

Executive producer Juliette Howell told Deadline the series will be a thriller that “gives these women and their children a voice.”

“The Good Mothers tells us about the women, not as accessories, but as fully rounded characters in their own right, as wives, mothers and daughters who show grit, determination and astounding courage in the face of the murderous misogyny of their husbands, fathers and brothers,” Howell said.

A release date for the series has not been set.

In a story for The Daily Beast website, Rome-based journalist Barbie Latza Nadeau noted that 42 women are among the hundreds of suspects on trial in Calabria. Underscoring the deep family relationships, Nadeau wrote, “One of the female suspects is charged with murder for attempting to carry out a vendetta on behalf of her incarcerated brother — although she was thwarted when the victim took a cyanide pill — as is common among mafiosi who use suicide to deprive their assassins of a successful hit.”

Nadeau noted that the number of women on trial “speaks to the seriousness with which the Italian court system is finally taking female organized crime suspects.”

“For decades, women were given a pass in Mafia trials, thought to be on the periphery or simply not smart enough to be involved, thus allowing them to fly under the radar,” she wrote.

Nadeau’s new book, Godmothers, is scheduled to be released this year. The book examines the role of women in Italy’s organized crime syndicates.

‘Dead man walking’

The intertwined relationships also include the Mancusos, a family said to control the Calabrian province of Vibo Valentia, “A leaf doesn’t move in Vibo Valentia without the say-so of the Mancusos,” Mafia expert Antonio Nisaco said in The Sun newspaper.

For assisting the prosecution in the maxi-trial, family member Emanuele Mancuso has received police protection. He is the son of Mafia boss Luni Mancuso, “The Engineer.” Emanuele Mancuso’s uncle, Luigi Mancuso, is the reputed leader of the clan. Luigi Mancuso’s nickname is “The Uncle.”

Gratteri understands the deadly risks Emanuele Mancuso and authorities such as himself face in challenging the ’Ndrangheta. In 2005, police uncovered a weapons stockpile intended for use in killing him. He has been called a “dead man walking.”

This is not the first time crime syndicates have threatened Italian prosecutors with reprisal. After a large trial in Palermo in 1986-87, Mafia hit men followed through on threats, killing prosecutors Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino. The trial in Palermo, targeting Sicily’s Cosa Nostra, resulted in 338 convictions.

Whether the current maxi-trial will cripple the ’Ndrangheta is up for debate. The syndicate is said to have 20,000 members. In addition, Italian underworld factions could be joining forces, potentially enhancing their power.

Public Prosecutor Federico Cafiero De Raho said the major syndicates are collaborating on cocaine shipments, money laundering and online gaming, according to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

The syndicates involved include the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta, Sicilian Mafia (Cosa Nostra), Campanian Camorra and Pugliese Sacra Corona Unita. Newer groups such as the Foggia Mafia and Gargano Mafia also might be aligned in this alleged one-syndicate empire.

“The most recent judicial developments make us see that this distinction of Cosa Nostra, ‘Ndrangheta, Camorra as different and separate criminal entities hardly corresponds to reality anymore,” Cafiero De Raho said. “The various Mafias operate together, as a single entity.”

Whether these groups are aligned or not, anti-Mafia prosecutors like Gratteri believe crime syndicates have a stranglehold on politics and commerce wherever they operate. Last year, unemployment in Calabria was 21.6 percent, the highest in Italy.

With few job opportunities and distrust of authorities, some in the region see the Mafia as a good option, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Children of ’Ndrangheta families have demonstrated this distrust by being tattooed on the bottoms of their feet with police-related images. This way they are always stepping on law enforcement, according to a Vice News report.

“On social issues, politicians are weak,” Gratteri told The Wall Street Journal. “The ‘Ndrangheta is much stronger. It offers hope.”

Gratteri is not without detractors. Some have accused him of being overzealous and interfering in politics. According to the the Wall Street Journal, Enza Bruno Bossio, a public official whose husband has been under investigation, said on Facebook, “Gratteri arrests half of Calabria! Is it justice? No, it’s just a show.” The post later was deleted.

Gratteri is not alone in this fight, however. Supporters have rallied outside his office in Catanzaro, cheering on his efforts, some chanting, “Don’t touch Gratteri.” These supporters hope this trial can unlock a brighter future for themselves and subsequent generations.

Gratteri told the Reuters news service the trial is “a kind of liberation for Calabria, a turning point that should allow people here to regain a freedom that has been denied them for many years.”

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org