The seedy side of Mob life

Movies based on George V. Higgins’ novels paint a harsh portrait of the underworld

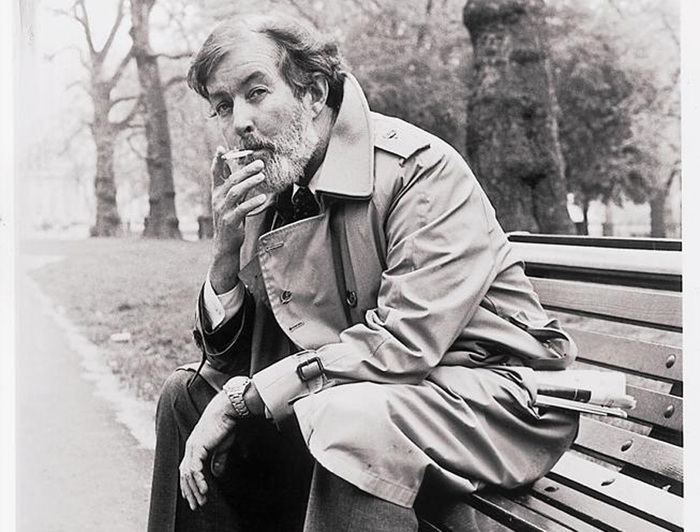

George V. Higgins, a former New England journalist and federal prosecutor who achieved acclaim as a novelist, disliked being pigeonholed as a crime writer, but his best dialogue-rich novels, including his first, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, published in 1970, are classics of the genre, filled with scheming, violent lowlifes and their demanding Mob overlords.

Two of his novels, The Friends of Eddie Coyle and Cogan’s Trade, were made into movies that paint a grittier picture of Mob life than popular films that arguably glamorize the underworld.

The movies based on his books can be considered a harsh antidote for those who favor realism over glamour in stories about criminals. With the summer vacation season coming on, which for some perhaps includes a little more movie-watching time, a comparison between the two styles could be worthwhile.

Even Mario Puzo, the New York City novelist who wrote The Godfather, conceded he romanticized the characters portrayed in his breakthrough best-seller about the Mafia. The 1972 movie based on Puzo’s book, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, became an iconic work of art characterized by memorable acting and solid cinematic storytelling centered on timeless themes of justice, family loyalty and power. To this day, it is how many in the movie-going public view Mafia figures.

Higgins’ stories aren’t like that. Novelist Dennis Lehane has written that Higgins, using his experience as an assistant U.S. attorney, “pulls back the veneer on the real criminal underworld.” In Higgins’ stories, “there are no noble gangsters swept up in high tragedy,” Lehane wrote.

Higgins’ early books such as The Friends of Eddie Coyle and Cogan’s Trade pre-date a 1980s movement in American literature known as Dirty Realism, defined by Bill Buford, then the editor the literary magazine Granta, as fiction about “the belly-side of contemporary life — a deserted husband, an unwed mother, a car thief, a pickpocket, a drug addict.”

Throw some shady Mob figures into the mix, and that description could fit Higgins’ work, though he came into prominence before Dirty Realism was recognized as a literary trend and, with his crime-writer label, wasn’t considered one of its high-art practitioners as Raymond Carver, Jayne Anne Phillips and others of their generation were. In that sense, however, Higgins’ genre-bending fiction was ahead of its time. Legendary crime novelist Elmore Leonard said The Friends of Eddie Coyle is the “best crime novel ever written.”

Also in his novels, Higgins, right from the opening paragraph, often plunges readers into a highly charged scene, choosing not to develop much of a backstory. This literary technique is called in medias res, or starting the story in the middle of the action. The famous first line of The Friends of Eddie Coyle is an example of that: “Jackie Brown at twenty-six, with no expression on his face, said that he could get some guns.”

This technique works especially well in movie-making, including crime dramas such as The Friends of Eddie Coyle. The 1973 movie stars Robert Mitchum, then in his 50s, as an aging Boston-area gunrunner, hoping he can beat a prison sentence on a previous charge by snitching to a federal agent on other criminals.

Behind the scenes is an unnamed Mob boss whose demands lead to a violent end for Eddie Coyle.

Mitchum delivers a strong performance, perhaps informed by his own run-ins with the law, including a long-ago Hollywood pot bust (“India hemp,” it was called), but also maybe by the New England gangsters he reportedly met with over dinner while The Friends of Eddie Coyle was being shot in and around Boston.

According to an online story by Howie Carr, a Boston author, journalist and radio talk-show host, Mitchum dined “most evenings during the filming with the two bosses of the Winter Hill Gang, Howie Winter and Johnny Martorano.”

The Winter Hill Gang later made international headlines when another of its leaders, James “Whitey” Bulger, was captured in 2011 across the country in Santa Monica, California, after 16 years on the run.

Incidentally, Santa Monica, a Southern California beachside town, is near the Laurel Canyon home where Mitchum, 31 years old at the time, and three others were nabbed in the widely publicized 1948 “demon drug” arrest.

After the arrest and trial, Mitchum spent a couple of months in custody as prisoner No. 91234 and was even visited by RKO studio chief Howard Hughes, who showed up in old khakis and torn sneakers, bringing the actor a brown paper bag filled with vitamins, presumably to supplement what Mitchum, with his one cup and spoon, referred to as the bowl of pudding “they shoved at me through the slot” at mealtime.

In his prison-issue denim blues and the expensive pair of brown Cordovans he was allowed to keep under house rules, Mitchum was generally left alone among inmates who, it could be guessed, were real-life characters of the kind he portrayed in noir movies of that day and in later big-screen crime classics such as The Friends of Eddie Coyle.

Those same sort of gritty characters are on full display in the 2012 movie Killing Them Softly, based on Higgins’ 1974 novel Cogan’s Trade. Typical of Higgins’ stories, the novel and movie focus not so much on the honchos at the top of the criminal hierarchy but on the violent grinders who occupy the lower rungs, the ones who work the trenches on behalf of shot-calling Mob heavies and their underbosses.

Starring Brad Pitt, Killing Them Softly zeros in on a team of misfits who knock over an underground card game — and then the violent street justice that ensues. The movie version is played out against an updated political and economic backdrop.

Pitt plays Jackie Cogan, a Mob hitman retained to eliminate the punks who robbed the tough-looking card players at gunpoint. Cogan completes the gruesome task after a New York hired gun portrayed by James Gandolfini goes on a drinking binge in a motel room and is revealed to be useless. This movie was one of the last cinematic appearances for The Sopranos star before he died in 2013 at age 51 of a heart attack.

Both movies — The Friends of Eddie Coyle and Killing Them Softly — faithfully represent the unsentimental worldview that Higgins puts forth in his novels.

The author came about his knowledge of the underworld by observing it as a reporter in two historically mobbed-up cities, Providence, Rhode Island, and Boston, and as a prosecutor and later a defense attorney.

An alcoholic who counted novelist Ward Just and other journalistic and literary high achievers as his friends and drinking buddies, Higgins died of a heart attack in 1999 a week before this 60th birthday. He published more than 30 books, most of them novels noted not only for their realistic dialogue but for their blunt portrayal of hardened criminals such as Eddie Coyle and Jackie Cogan.

In the books and movies, nothing about these characters is glamorous.

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. Henry taught journalism at Haas Hall Academy in Bentonville, Arkansas, and now is the headmaster at the school’s campus in Rogers, Arkansas. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org