A Mob boss sings, incognito

Thirty years ago, Cleveland Mafia chief Angelo Lonardo defied tradition to testify about his crime family’s dirty secrets

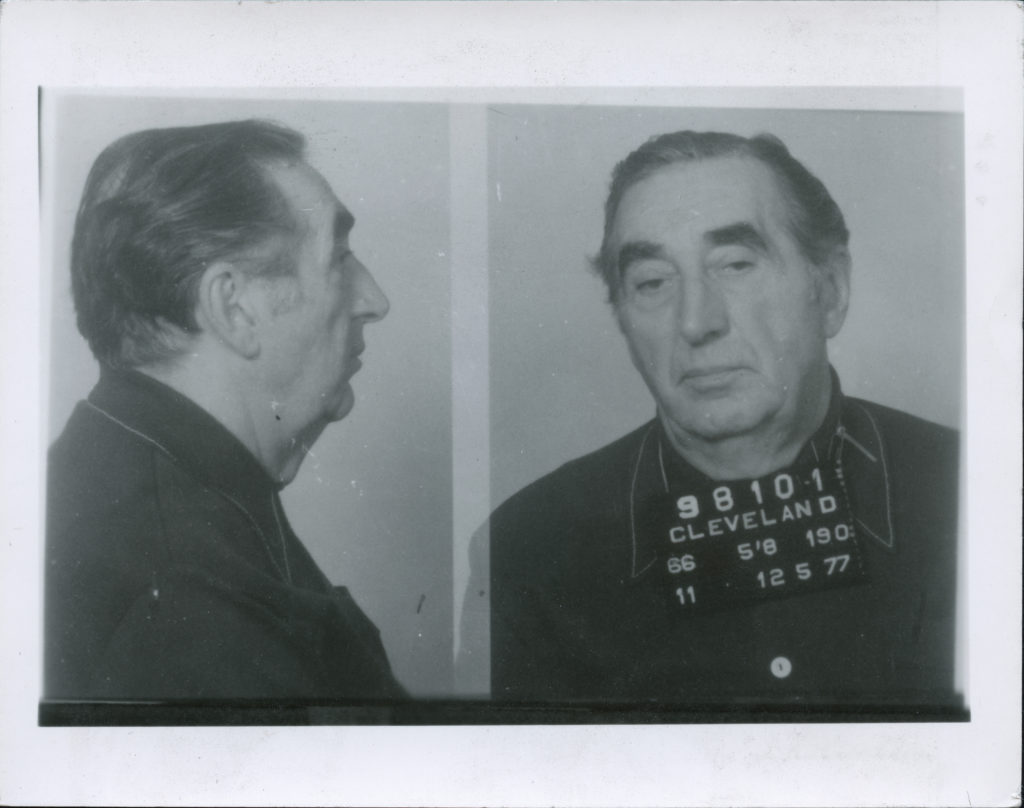

Cleveland Mafia boss Angelo “Big Angie” Lonardo was the first sitting American Mafia don to become a witness for the government. Thirty years ago, on April 15, 1988, Lonardo testified before the U.S. Senate, delivering lurid details of the Midwest Mob’s skimming of Las Vegas casinos and providing a behind-the-scenes look at the inner workings of Mafia politics. His testimony covered several powerful gangland empires spanning from his one-time headquarters in Ohio all the way to the highest levels of the underworld in New York.

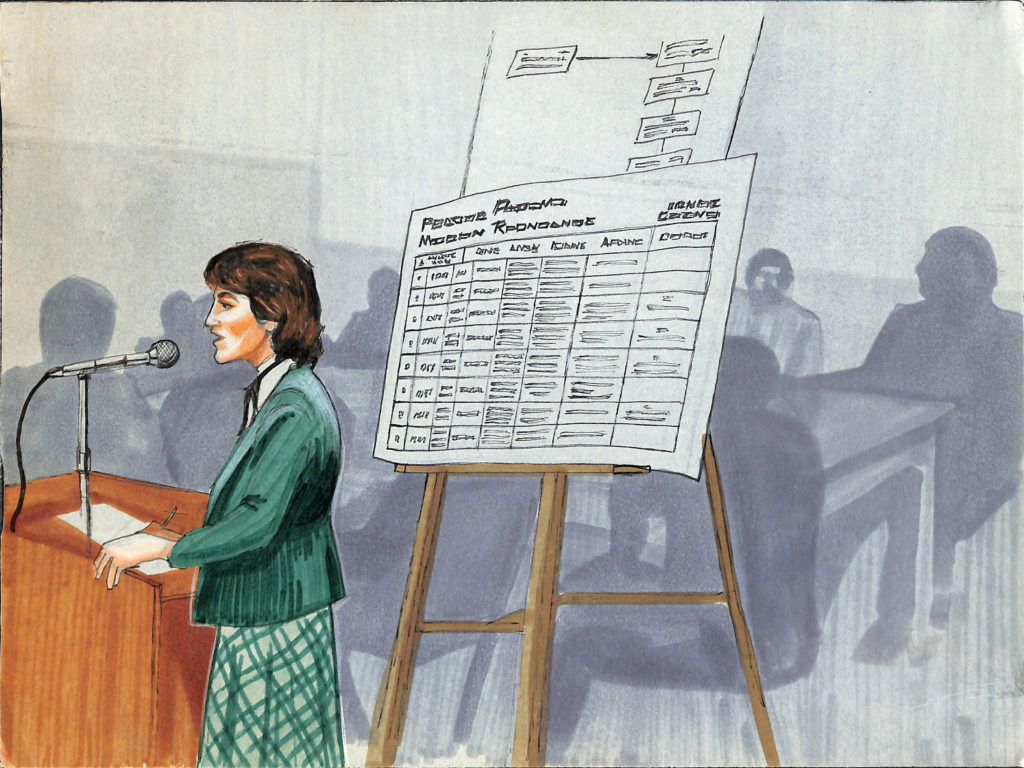

On that spring day in 1988, Lonardo, hidden behind a screen to shield his face, read a prepared statement to the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, part of the Committee on Government Affairs.

Lonardo flipped in 1985 while serving a prison sentence for narcotics trafficking. He took the stand in the famous “Commission Trial” the following year, one of the star witnesses in the landmark case against the godfathers of the Five Families in New York brought by future New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, then an ambitious U.S. attorney looking to make a name for himself in the public eye.

In 1981, Lonardo was named “acting boss” of the Cleveland Mafia upon then-boss James “Jack White” Licavoli’s incarceration. A few years before Lonardo began his cooperation, the former acting boss of the Los Angeles Mafia, Aladena “Jimmy the Weasel” Fratianno, entered the witness protection program, becoming the first official Mob leader to turn “rat.” Fratianno had once been a member of the Cleveland crime family. Philadelphia don Ralph Natale became the first full-fledged Mafia boss to cooperate with the FBI in late 1998.

According to Lonardo’s Senate testimony, the Cleveland Mafia’s foray into Las Vegas began early on in the development of what became the Strip, when businessman Wilbur Clark was in need of additional funding to complete the construction of the Desert Inn, which he would receive through the Jewish arm of the Cleveland Mob. The Ohio racketeers went on to provide Clark with protection in his Las Vegas business dealings, mainly through Moe Dalitz, their representative in the city.

The Cleveland Mob group later wrangled itself a piece of the Stardust hotel-casino too. Skimmed money from casinos in Las Vegas continued flowing into the coffers of Mafia chiefs in the Buckeye State through the 1980s. Beginning in the 1970s, the crime family joined forces with crime factions in Milwaukee, Kansas City and Chicago to strengthen its grip on the Las Vegas gaming industry.

Lonardo’s Mafia lineage dates back to Prohibition. His father, Joe, was the first boss of the Cleveland Mafia, slain in 1927 by his second-in-command, Salvatore “Black Sam” Todaro. The younger Lonardo, only a teenager, retaliated by killing Black Sam two years later, luring him to a meeting with his mom in June 1929 and shooting him to death in broad daylight.

Soon thereafter, Lonardo was convicted of Todaro’s murder and sentenced to life in prison. But the conviction was overturned on appeal. His avenging of his father’s assassination, which years later included the murder of another conspirator and Cleveland Mafia statesman named Giuseppe “Dr. Joe” Romano (a mobster and physician), earned him the respect of the local crime family. He was formally inducted into the Mafia in a 1940s ceremony and soon rose to the role of captain.

Lonardo also testified about his knowledge of labor union corruption and the downfall of the Cleveland Mob. He chronicled how the Mafia controlled the shifts of power in the Teamsters Union, especially in regard to the union’s pension fund, which helped finance casino purchases and construction in Las Vegas. He described how a reluctance to inject fresh blood into the syndicate, and an upstart band of Irish gangsters eager to take advantage of the personnel shortage, resulted in a street war over racket territory, an increase in drug-dealing activity to make up for the organization’s thinner ranks and eventually the mass imprisonment of its leadership.

Lonardo said that Cleveland Mafia’s brass frequently traveled to New York in the 1970s to meet with Genovese crime family street boss Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno in order to clear policy decisions. The Genovese clan represented the Cleveland Mafia on the Commission, the Mafia’s national board of directors. Lonardo was promoted to underboss in 1976 in the wake of the unrest in Cleveland. His conviction and imprisonment for overseeing a cocaine conspiracy in 1983 inspired him to cooperate with the feds and go public with his revelations.

Living in retirement back in the Cleveland area following his reduced prison term and quitting the witness protection program, Lonardo participated in a documentary titled Sugar Wars — not released until after his death — recalling the local Mob feuds he had lived through. Big Angie Lonardo died in his sleep on April 1, 2006, at age 90.

Scott M. Burnstein, a journalist and true crime historian, is the author of five books on organized crime. He founded and runs The Gangster Report (www.gangsterreport.com) newsmagazine website. He writes daily for The Oakland Press in Metro Detroit and focuses on Mob activity in Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia and New England.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org