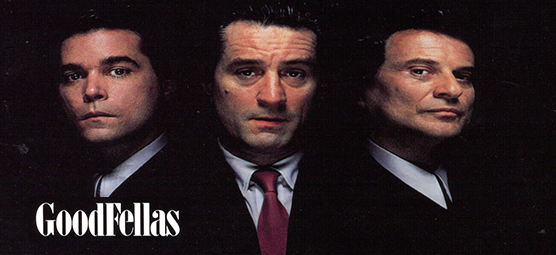

Mob classic “Goodfellas” debuted in theaters twenty-five years ago

Martin Scorsese movie still resonates today

Monday marks a quarter-century since Goodfellas was released in American theaters. It was the highest-grossing movie of the September 21-23, 1990, weekend, beating eventual big box office hit Ghost. Before hitting 1,070 screens that first weekend, Goodfellas, based on a real-life New York Mob associate who became an informant and prosecution witness, met with almost universal critical praise.

“For two days after I saw Martin Scorsese’s new film, Goodfellas, the mood of the characters lingered within me, refusing to leave,” wrote Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert. “No finer film has ever been made about organized crime — not even The Godfather, although the two works are not really comparable.”

“Goodfellas looks and sounds as if it must be absolutely authentic,” wrote Vincent Canby of the New York Times. “The authenticity exists in the unimaginative ordinariness of the violent lives it depicts. These guys [whack] an associate with ease and then stop by [Tommy DeVito’s] mother’s house to pick up a shovel. The old lady insists on feeding them.”

But among films released in 1990, Goodfellas would end up ranking only twenty-sixth, grossing $46.8 million at theaters. Goodfellas received six Oscar nominations and won one (Joe Pesci for supporting actor as Tommy DeVito). Dances With Wolves, with a box office draw of $184 million, took the cake, garnering seven Oscars, including Best Picture, and its star Kevin Costner took home Best Director over Scorsese.

Twenty-five years later, Goodfellas and its characters remain far fresher in the public mind, and more enjoyable on multiple viewings, than Costner’s Western.

In April, actor Paul Sorvino, flanked by Goodfellas co-stars Robert De Niro, Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco, told NBC’s Today Show: “People come up to me every day, every day, I swear to you, and tell me it’s their favorite movie. And it’s on [TV] every day. So it touched a chord in everyone.”

Goodfellas is based on Nicholas Pileggi’s 1986 nonfiction book Wiseguy about Henry Hill, a Mob subordinate of Irish and Sicilian parentage. Hill worked with the Lucchese family in New York starting as a gofer at age 11 in 1955. Under the leadership of Lucchese crew head James “Jimmy the Gent” Burke in the 1960s, Hill graduated to contract murders, drug trafficking, fraud, truck hijackings, extortion and loansharking.

Like Burke, Hill could function in the Sicilian Lucchese Mafia family but not become a made member because of his Irish heritage. In the mid-1960s, Burke introduced Hill to a teenage Tommy DeSimone, whom Hill would later regard as a psychopathic killer. Hill helped Burke’s crew plan the successful 1978 armed robbery of $5 million in cash – then the largest theft of cash in U.S. history – from Lufthansa at JFK Airport in New York. Burke had several of the co-conspirators in the heist killed to silence them and keep more of the money for himself. Hill’s run with the Mob ended in April 1980 when he was arrested for drug trafficking. Fearing he was targeted for death by Burke, Hill agreed to enter the federal Witness Protection Program a month later. He testified for the U.S. attorney’s office in trials that sent dozens of mobsters to federal prison, including Burke and Lucchese capo regime Paul Vario (Sorvino’s character Paul Cicero in the movie).

That’s the overall story, but why does the R-rated, 146-minute Goodfellas still resonate today? Is it the sum of parts? Pick one.

There’s Scorsese’s influential use of voiceovers, freeze frames and fast-cut editing (by editor Thelma Schoonmaker) that he said was an homage to French director François Truffaut’s techniques in the 1962 film Jules and Jim. Scorsese’s soundtrack weaves hit music from the 1950s to 1970s into his shots. One is the well-known, 184-second tracking shot (by cinematographer Michael Ballhaus) of Liotta (as Henry Hill) walking with Bracco (as Hill’s wife Karen Freidman) through the rear of the Copacabana club to 1963’s “Then He Kissed Me” by girl group The Crystals. Bodies of Lufthansa heist participants rubbed out by De Niro (as Burke’s character Jimmy Conway) are shown to the tune of Derek and the Dominos’ “Layla” from 1970. De Niro and Pesci (as DeVito, based on DeSimone), kick and pistol whip a doomed Mob capo “Billy Batts” to Donovan’s 1969 “Atlantis.”

But likely the most celebrated parts of Goodfellas are the characters’ lines within scenes that are so famous today they are listed and much-viewed on YouTube. While Pileggi and Scorsese collaborated on the screenplay, some of the dialogue came from transcripts Scorsese made from recordings of ad-libbed conversations by actors Pesci, De Niro and Liotta while in character. Here’s a short list:

- At the start of the film, after De Niro and Pesci do away with “Billy Batts,” Liotta says in a voiceover, “As far back as I can remember I’ve always wanted to be a gangster.” In the next scene, with Tony Bennett’s 1953 “Rag to Riches” playing to the opening credits, Liotta then says: “To me being a gangster was better than being president of the United States.”

- Perhaps the best-known Goodfellas clip is the “Funny how?” scene in the Bamboo Lounge in New York, where Pesci is joking with Liotta and the crew, and seems to take offense when Liotta says, “You’re a funny guy.” To which Pesci replies, “I’m funny how, like I’m a clown. I amuse you?” Pesci said he based the dialogue on a similar conversation he once heard between two Mob-types.

- De Niro and Pesci end up beating up “Billy Batts” (played by Frank Vincent) after the mobster insults Pesci, once a shoeshine boy, by saying “Now go home and get your f—cking shine box!”

- After the beating of “Billy Batts,” Pesci proposes they go his mother’s home to get a shovel. At her home, Pesci’s mother (played by Catherine Scorsese, the director’s mother), makes the three men something to eat. Pesci admires one of her paintings with two dogs in a boat. “I like this one. One dog goes one way, the other dogs goes the other way.”

- Pesci berates a drink server named Spider, who is recovering from being shot in the foot by Pesci during a card game. Spider then tells Pesci off. De Niro jokes to Pesci, “Are you going to let him get way with that? …What’s the world coming to?” Pesci the impulsive psychotic, to the shock of everyone, shoots the kid dead.

- Hill’s Jewish wife Karen watches the mostly Italian-American wives of the mobsters at a women’s-only gathering. “They had bad skin and wore too much makeup. They looked beat up. And they talked about how rotten their kids were and about beating them with broom handles and leather belts.”

There are many other memorable scenes – Sorvino using a razor blade to slice garlic while cooking in prison, the TV commercial where the toupee salesman Morrie Kessler (Chuck Low) leaps backward into a pool. Funny how this was a movie that sent audiences to the exits in droves during pre-release test screenings, apparently in reaction to the film’s violence — shootings, stabbings, beatings and strangulation.

The influence of Goodfellas on modern culture has been considerable. The TV writer David Chase said Goodfellas was “the Koran for me” in his creation of HBO’s The Sopranos series. Jim Hemphill of Filmmaker magazine wrote this year that the style and the moral ambiguity of characters in Goodfellas motivated and permitted American directors throughout the 1990s to make films such as Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Get Shorty, Boogie Nights, Natural Born Killers and Fight Club. And as the impetus for The Sopranos, the movie also led to the acceptance of TV shows such as Breaking Bad, Mad Men and Six Feet Under, according to Hemphill.

“After a decade in which the American cinema was largely characterized by its complacency in the form of movies like Rambo and Top Gun that showed us how great we all were, Goodfellas served as a necessary challenge to conformity (both political and stylistic) and inspired Hollywood movies to grow up again – at least for a while,” Chase wrote. “It didn’t last, but then, as Henry Hill himself knew, the glorious times never do.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org