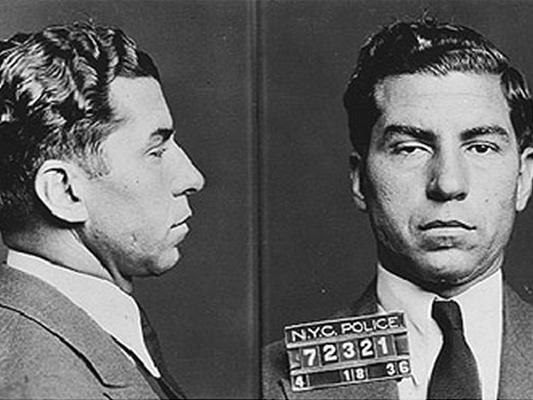

Lucky Luciano

Born: November 24, 1897, Sicily, Italy

Died: January 26, 1962, Naples, Italy

Nicknames: Lucky, Charlie Lucky

Associates: Arnold Rothstein, Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello, the Five Families, the Commission, Bugsy Siegel

Charles “Lucky” Luciano, born Salvatore Lucania in 1897 in Sicily, probably did more to create the modern American Mafia and the national criminal Syndicate than any other single man. Luciano led a group of young Italian and Jewish mobsters against the older set of so-called “Moustache Petes,” and in the process set the stage for the Mob to grow beyond the limits of bootlegging profits to become, in the words of his friend Meyer Lansky, “bigger than United States Steel.”

Luciano, who moved to the United States and settled in the Lower East Side with his family at age 10, was recruited early into gangster life and was a member of the Five Points Gang in Manhattan. Around the start of Prohibition in 1920, he was recruited as a gunman by Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria, and a few years later Luciano went to work for Arnold Rothstein, another seminal figure in early organized crime. By the mid-1920s, Luciano was reportedly making millions in bootlegging profits.

With Rothstein’s murder in 1928, Luciano went back to working for Masseria, who by this time was the self-styled “Boss of Bosses,” and who was going to war with a rival, Salvatore “The Duke” Maranzano.

Luciano secretly sided with Maranzano in the bloody Castellammarese War and helped set up Masseria for assassination in 1931. Before the end of the year, Luciano and other “Young Turks” would knock off Maranzano, and the era of the Old World “Moustache Petes” would be over.

With Maranzano’s assassination, Luciano inherited the crime family by a gang from Murder, Incorporated – allegedly including Joe Adonis, Bugsy Siegel, Albert Anastasia and Vito Genovese, all of whom would go on to well-known roles in the Mob — Luciano inherited the crime family that would eventually become known as the Genovese family. A natural organizer, Luciano continued the committee of Five Families, which was established by Maranzano and would control East Coast rackets for decades. But rather than naming himself “Boss of Bosses,” as Maranzano had, Luciano called himself the chairman of the board.

Further, he established and hosted the first national meetings of what became known as the Commission, a national criminal syndicate, all in the name of avoiding unnecessary bloodshed and maximizing profits for all the families.

But all of that meant Luciano was a very public leader of the Mob, and that drew attention from law enforcement, and specifically from a young prosecutor in New York named Thomas Dewey. Dewey and his assistant, an African-American attorney named Eunice Carter, noticed that many of the prostitutes who were being arrested were represented by the same bondsmen and attorneys working for Luciano.

Armed with this information, in 1936, Dewey led raids on brothels throughout the city, arresting more than 100 people, mostly women, many of whom were unable to post the bail of $10,000 set by the courts. Some of those arrested provided information to the prosecutors that led to Luciano’s arrest and trial that same year. On June 6, 1936, Luciano was convicted of 62 charges of compulsory prostitution; he was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in state prison.

Luciano turned over leadership of the national Commission to Frank Costello.

That wasn’t the end of Luciano’s story, however. During World War II, the government needed the Mob’s help to keep the New York docks free of strikes, sabotage and other problems. Luciano agreed to help, on the assumption that he would get a break on his sentence. Dewey, the former prosecutor, was now New York governor and in a position to grant clemency.

After the war ended, Dewey commuted Luciano’s sentence with the understanding that the Mob leader would leave the United States, which he did, returning to Italy as a deportee. Luciano still maintained his ties to the American Mafia as a sort of elder statesman. The same year that he debarked to Italy, Luciano came to Havana, Cuba, and along with hobnobbing with celebrities such as Frank Sinatra, hosted a meeting of top-level mobsters from all the major American crime families.

Pressure from the U.S. government – specifically a threat to ban the export of American medicines to the island country – forced the Cuban government to deport Luciano back to Italy.

Luciano spent the rest of his life under close Italian police scrutiny. Luciano often met with American tourists and sailors and frequently professed his love for the United States. He died of a heart attack in 1962 at the Naples airport, where he had gone to meet with a movie producer considering a biography of Luciano.