Was 1929 Atlantic City Mob meeting a strategy session to address the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre?

Al Capone tells cops: ‘I spent the week in Atlantic City and I have (their word) that there shall be no more shootings’

Ninety years ago this week, “America’s Playground” – Atlantic City, New Jersey – played host to a mysterious convening of gangland’s established and rising Mob stars. From May 13-16, 1929, the overlords of the nation’s vice rackets rolled into the ocean-front town for what was later considered the first of three major Mob conferences held during the 20th century. Some historians consider it the most significant of the trio (Havana in 1946 and Apalachin in 1957 were the others), and probably the largest. The invitees arrived from the Midwest, New England, Philadelphia, New York, Detroit and possibly as far away as Florida. So then, if such a momentous event actually occurred, who was there and why?

The heyday of the underworld’s Prohibition spoils came to a head in 1929 when bloodshed, infighting and territorial disagreements between criminal competitors culminated in the most heinous act yet –Chicago’s St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. The Chicago conflict was, however, only one of many atrocities related to gang warfare, all of which the public and law enforcement had grown tired. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre simply drove the final nail and simultaneously gave the world an official “poster boy” for organized crime – Al Capone.

The cops were not the only ones eager to tone down the violence. Notoriety is bad for business, and the fallout forced the Mob to strategize on damage control. The contingency plan was two-fold. First, the nation’s gang leaders recognized the obvious and immediate need to ease heat from authorities. The second major goal was establishing a long-term plan that, in theory, would avert similar violent flare-ups.

The story goes that sometime over the few months following the Massacre, the top gangsters decided to hold meetings where affected parties could come together safely, without fanfare and with assurances of neutrality. Atlantic City was the chosen place, and its boisterous boss man charged with all the necessary arrangements. Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, a polarizing and contentious figure in 20th century political theater (and within gangland circles), fit the bill because, simply put, under his control Atlantic City had an “anything goes” policy.

Nucky had a stake in the issues at hand as well. An assortment of (primarily) Italian and Jewish crime lords, flanked by their trusted entourages of advisers and bodyguards, descended on the Breakers Hotel in Atlantic City in mid-May 1929. Notably, and understandably, not present were the two warring New York Mafia dons – Joe “The Boss” Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano. Hotel managers frowned on guests seen as having unsavory reputations and refused to accept the men’s reservations (which allegedly provoked a scene or two in the hotel lobby). Despite the power Nucky Johnson wielded, his efforts to rectify the situation had little effect on the hotel’s ethnic prejudice. He had to relocate the cast of characters to the President Hotel instead. Once settled in, the gang got down to business on May 13.

Was the event a success? One scheme hatched by the crime lords went into action immediately at the summit’s conclusion. On May 16, Al Capone and his bodyguard Frank Rio (aka Cline) boarded a train bound for Philadelphia. They arrived there at 6:30 p.m. Police recognized them and began following the pair. Capone and Rio casually took in a movie while the cops waited outside. At 8:30 p.m., as the men left the theater, police detained them, found them to be carrying concealed weapons and took them into custody. In less than 24 hours, Capone was tried, convicted and sentenced to a year in prison. More importantly, the Chicago crime boss divulged tidbits of information to the interviewing officer, Director of Public Safety Lemuel Schofield. Capone didn’t name names, never revealed any specifics that would compromise or violate the Mob’s oath of silence, but made it clear he had been in Atlantic City for a gangland truce.

“I want peace and I am willing to live and let live,” Capone told Schofield. “I’m tired of gang murders and gang shootings. With the idea in mind – of making peace among the gangsters of Chicago – I spent the week in Atlantic City, and I have the word of each of the men participating that there shall be no more shootings.”

According to legend, it was all part of the plan, methodically designed and ratified by the board of bad guys. Capone and Rio, each carrying handguns, would be arrested, charged with possessing a weapon, serve a little jail time and hopefully everything relating to the Massacre would cool off. Immediately following Capone’s conviction, some authorities in Philadelphia publicly theorized that the arrest was a ploy by gangsters.

To say the entire Massacre hype died down after Capone’s short prison sentence is stretching it a bit. Granted, Capone did as he was told and underworld heat cooled enough for other major developments in the Mob to evolve. Capone’s “tell all” moment, vis-à-vis the so-called Atlantic City crime summit began to take on a life of its own, raising more questions for years to come, not the least of which was: Did any of this scheming really happen? Seems that not everyone can agree, but 90 years later, the mythos of Atlantic City’s Mob fest still stirs up conjecture, argument and debate. Two prominent theories emerged of what probably did or did not go down in Atlantic City from May 13-16, 1929.

1. Standing room only: Enoch “Nucky” Johnson hosted all the prominent Midwest and East Coast gangland figures for the summit in Atlantic City. The purpose: to work out territorial disputes, importing, payoffs, distribution, and dealing with the specific problem in Chicago – Capone’s Outfit vs. Bugs Moran’s North Side Gang.

2. Limited engagement: Johnson facilitated a meeting of mostly Chicago-based gangsters. The purpose: to settle the problems between Capone’s faction and other Midwestern bootleggers.

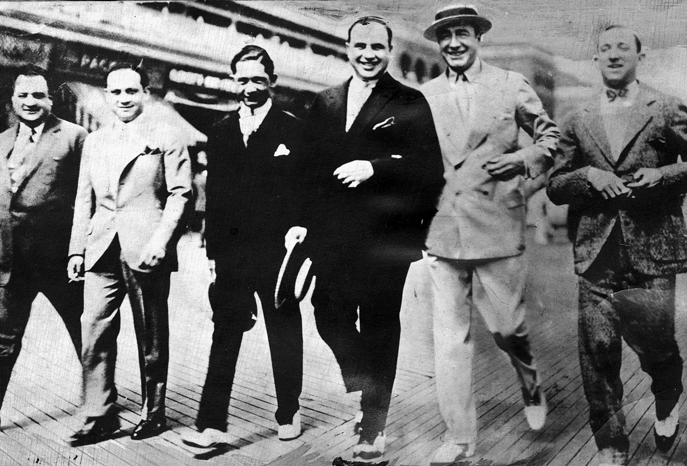

Because the Mob didn’t keep detailed meeting notes, nor did they publicize their meetups, finding the truth within lore is sometimes as elusive as the gangsters themselves. Detractors point to the (limited) literal evidence (Capone’s own words), dismissing the tale of a national crime ensemble, and leaning toward the more “realistic” scenario that just the Chicago boys convened. Then there are even those who reject the tale altogether, pointing to circulating accounts claiming the infamous New York Evening Journal cover photo (Al Capone and Nucky Johnson walking along the boardwalk) was merely a composite, fashioned to cast bad publicity on Nucky Johnson, created by the paper’s owner. Years later, Johnson, responding to a reporter’s request for a photo, seemed to validate the authenticity of the Evening Journal picture.

“Some photographer caught me with Al Capone once,” Johnson said in the 1941 news story. “From now on I’m being careful.”

Proponents of the large-scale convention story point to clues, such as Meyer Lansky’s purported presence in Atlantic City for a honeymoon with first wife, Anna Citron, during the same week as the convention. There is also an elusive, yet very real, photograph that occasionally floats around the Internet, depicting Al Capone, Ciro “the Artichoke King” Terranova and Charles “Lucky” Luciano, all smiles, wading in the hotel’s indoor swimming pool. They also rely on basic logic. No single city or entity involved in the “beer wars” was autonomous — it affected the entire organized criminal underground. The fact is that Capone was very much involved with his friends from New York and beyond, most prominently his own mentor, Johnny Torrio. What happens in one region ultimately benefits or has consequences for all.

Those who believe that the criminal all-star convention did happen also cite the 1939 testimony of drug trafficker Yasha Katzenberg during Torrio’s tax evasion trial. Katzenberg described the formation of a crucial (albeit short-lived) liquor and drug cartel known as the “Big Seven” (aka The Seven Group) that had established divisions and turf. Although Katzenberg made no specific mention of Atlantic City or the convention, it is conceivable that the idea of forming the Big Seven group would have been the Mob’s response to the fallout of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre fiasco, and ratified only during a meeting of most of the biggest players of the time.

Christian Cipollini is an organized crime historian and the award-winning author and creator of the comic book series LUCKY, based on the true story of Charles “Lucky” Luciano. Go to www.ganglandlegends.com.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org