Top five mobsters you’ve probably never heard of

Many organized crime figures who once made headlines have faded into history

In researching American organized crime through decades-old newspapers available online, it’s amazing how many significant Mob figures gained infamy and broad coverage of their exploits in their time, only to virtually disappear from memory.

The history of the 20th century contains many stories of notable true crime characters who dared to flout state and national laws, some through violence, and others avoiding it, for profit. They had their ride of “success” as criminals, came and went, and now exist only in imperfect, fast-written, snapshot news articles, official police and court documents, interviews and unreliable but entertaining gossip and hearsay.

We found quite a few compelling stories about forgotten members of one-time syndicates, large and small, and picked a handful of the best. Below is our list of the top five mobsters you’ve probably never heard of.

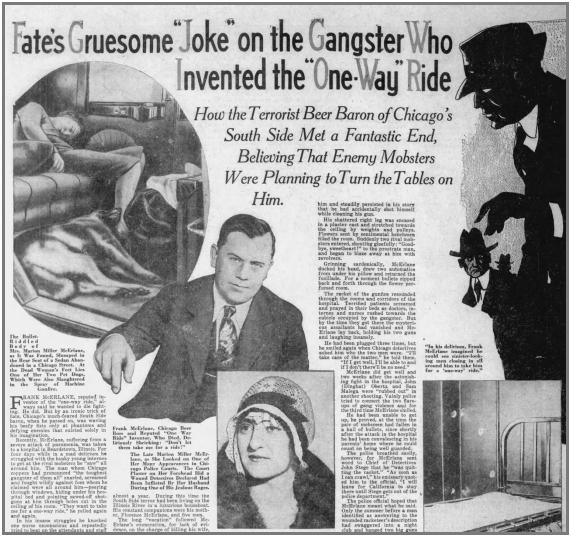

Frank McErlane

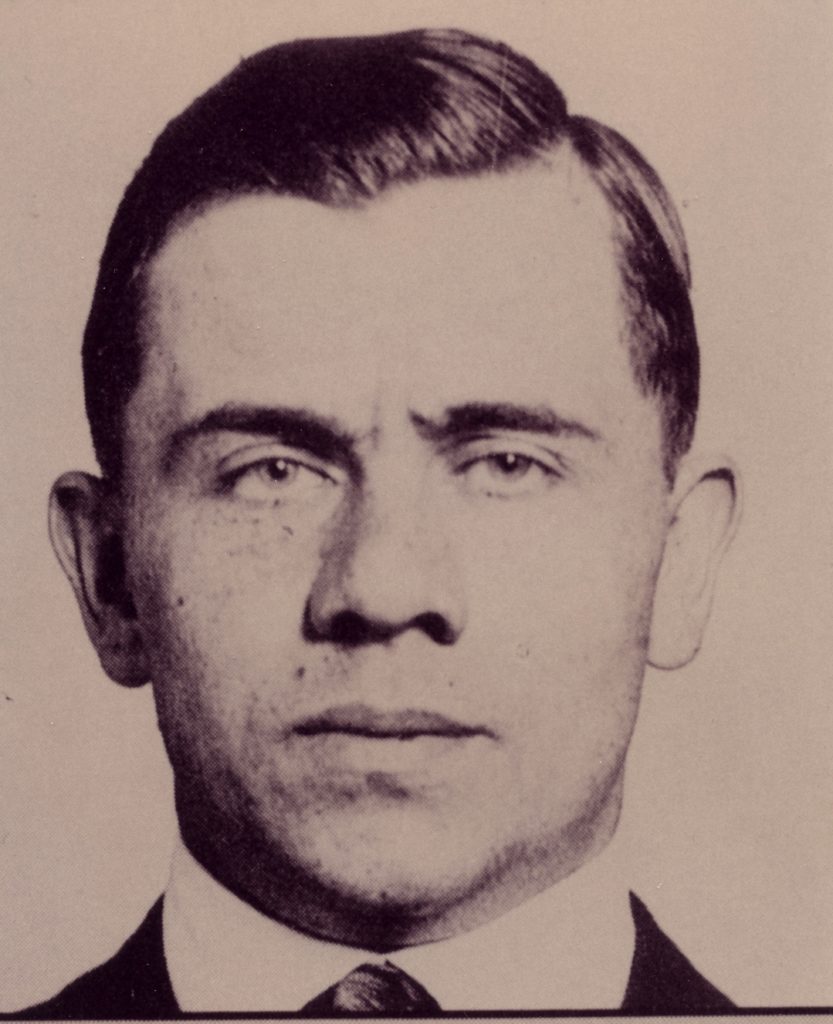

Upon his death from a torturous, four-day bout with pneumonia in 1932, Frank McErlane was described by Chicago Police as the “toughest gangster of them all.” His ruthless bootlegging peers in the Windy City feared him so much they reportedly paid him a “pension” of hundreds of dollars a week just to stay out of town.

McErlane, with the Saltis-McErlane Gang of the city’s South Side, was as cruel and mean as any in gangdom and a maximum danger when blackout drunk and armed. Chicago lore credits him as the first mobster to use a Thompson submachine gun in an attempted gang hit, and with originating the term “one-way ride” to describe a doomed hit target. During his marathon pneumonia delirium, medical attendants heard him scream, “Don’t let them take me for a ride!”

Born in Chicago in 1894, McErlane slid into crime by his late teens. During Prohibition in 1922, with his partner Joseph Saltis, he signed up with the Outfit bootlegging gang led by Johnny Torrio and Al Capone. McErlane proved himself a merciless killer during the Outfit’s “beer wars,” slaying three members of a rival liquor gang run by Edward “Spike” O’Donnell.

McErlane’s ill-famed debut of the Tommy gun during the beer wars occurred on September 25, 1925, with O’Donnell his intended victim. The Thompson, created as a military weapon, could fire 100 .45-caliber shots in five seconds. O’Donnell, standing outside a drugstore at 63rd Street and Western Avenue, ducked below a nearby auto as McErlane’s burst shattered the store’s window. His next episode with a Thompson took place that October 3 at the Regan A.C. Clubhouse on 52nd Street. Again, his rata-tat-tat missed the wished-for gangster, “Dynamite Joe” Brooks, but killed an innocent bystander.

As of 1926, McErlane’s liquor gang had murdered 15 people, beating the raps time after time – as witnesses dreaded retribution — and robbed a mail train of $135,000. The gang at that time of open street combat controlled the South Side illicit beer and liquor racket. McErlane somehow avoided death while the object of a dozen shootings. In 1927, he and his gang member brother Vincent rebuffed attempts by police to undergo mental testing for a possible hold in a psychiatric hospital. The Chicago Crime Commission placed Frank on the city’s 28-member “public enemies” list, headed by Al Capone.

Even worse, in what Chicago cops then regarded as the most brutal killing of the century, in October 1931, a drunken McErlane used a Thompson to unload slugs into the rear of an open car containing his common law wife, Marion, killing her and her two dogs. McErlane abandoned his vehicle and made his way out of town. Police right away suspected McErlane as the triggerman, figuring, in one news account, “no one but Frank could be so cruel.” Officers looked for him for eight weeks as he stayed on the lam in Madison, Wisconsin, then turned himself in. Arrested and held on $25,000 bail, McErlane won out again. A coroner’s jury ruled that Marion had been murdered, but since there were no witnesses, McErlane got off scot-free.

He served time in jail for robbery, assault to murder, assault to kill, accessory to murder, burglary and aiding a prison escape (he helped a convicted murderer out of the Cook County jail). Though he killed multiple people, he never did time for murder. While on the sauce, he tended to go wild, roaming up and down the streets of the South Side firing a shotgun at imaginary pedestrians. In one such case, after police picked him up, he told of seeing a “large army of green snakes and pink elephants. They tried to bump me off, but I beat them to it.”

Once, in an argument with his wife Marion, she shot him in the leg, causing a fracture. While in a Chicago hospital with the broken leg, a group of gunmen thrust into his room, guns blazing. McErlane, wounded three times, grabbed a pistol from under his pillow and returned fire as the assailants took off.

In the last months of his life, McErlane lived on a houseboat far from Chicago, in Beardstown in western Illinois, with his mother. He entered a hospital there on October 4, 1932, and died four days later. Considered a pauper, McErlane was buried in a cheap coffin. But his reputation lived on for a bit. According to The Courier newspaper of Waterloo, Iowa, his family opted to keep the location of his funeral a secret since “it was feared enemies might attempt to maim the body.”

Salvatore and Rosario Maceo

Salvatore “Sam” Maceo joined his brother Rosario, or “Rose,” at the Gulf Coast island city of Galveston in southern Texas around 1915. Both were immigrants from Palermo, Sicily, in the early 1900s, not members of the Mafia per se, but surely acquainted with Mafia activities while growing up.

After serving in the Army during World War I, the 30-year-old Sam returned to Galveston, where he and Rose (age 33) served as barbers, but strained to make a living at only 25 cents a cut. Rose’s shop stood on Murdock’s Pier over the beach and gulf. There, in 1921 during Prohibition, a man named Dutch Voight became a regular customer. Voight was the leader of Galveston’s Beach Gang of bootleggers. Voight paid Rose $1,500 to hide some bottles of illegal liquor for a few days.

The brothers determined to switch to running illicit booze, with Sam opening a soda stand on the pier as a front. They soon took advantage of the instability and weaknesses of the Beach Gang, and its lessor rival Downtown Gang, and won the leadership of both. Their organized crime rackets would remain in business there until 1957, after their deaths.

The Maceos, in an unusually short time, expanded their bootlegging racket with a speakeasy offering illicit gambling, called the Hollywood Dinner Club. Sam served as the main operator and public face of their “gang,” and Rose as the discreet enforcer. They took over and reopened a Chinese restaurant in 1926, called Maceo’s Grotto. In 1927, local sheriff deputies raided the Hollywood Dinner Club and bashed in its slot machines, roulette and other gaming tables.

The brothers soon resumed bootlegging and gambling, expanded to houses of prostitution and bookmaking, and paid off city officials. They used the end of the pier to quietly unload bootlegged liquor from Cuba, trucked it east to New Orleans and as far north as Cleveland. Meanwhile, residents of Galveston, long an “open city,” tolerated the vice racket as tourism, jobs and prosperity boomed with it.

Sam, affable, kind and a sharp dresser, gained fame as the chief spokesman for the sandbar island city as a tourist mecca. At the end of the glittering pier, the Moorish-style Hollywood speakeasy, with its lavish interior, included a palm tree-lined drive used by wealthy high-rollers lining up in limousines and luxury cars. He booked top national big band leaders such as Guy Lombardo. After a hurricane damaged the Grotto, Sam reopened it in 1932 as the Sui Jen, a high-class, Chinese-themed café. He held sought-after cruise parties on the gulf in his yacht in Galveston Bay. Newspapers referred to him as the “Night Club King.”

In 1934, Sam told an interviewer: “We break the law, but in a way that people like. We give them what they want.” He added that the island had to be accessible to vice services to survive. “No resort can be a resort unless it’s wide open. Otherwise, Galveston would be nothing.”

Ever the crowd pleaser, Sam sprung for large Christmas parties for adults and local orphans, bankrolled professional and amateur boxing matches and owned the area’s minor league baseball team, the Galveston All-Stars.

Disaster struck in 1937 when narcotics investigators claimed Sam had joined a $10 million national heroin-smuggling syndicate that imported the drug in ocean liners to New York and trafficked it in New Orleans, Waco, Houston and San Antonio. Sam admitted he knew two of the dozens of people indicted, but vehemently denied taking part. In 1942, he and his wife, Edna, wept in court in New York after a jury found him not guilty.

Now in the clear, he built his best nightspot yet, the Balinese Room, a private club with dinner, dancing, gambling, bookmaking and an ocean view from the pier. He also held interests in swank establishments such as the Studio Lounge, Western Room, Turf Club, Crystal Palace and Murdoch Bathhouse and Pier.

The Texas Rangers raided the Balinese Room many times, but Sam was ready – using electric buzzers as a warning, the staff hid the gambling tables and had patrons innocently play checkers and dominoes. Sam booked Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett to perform. In the late 1940s, the Maceos made a hefty investment with Cleveland Mob figure Moe Dalitz in the Desert Inn hotel-casino in Las Vegas.

In 1950, Sam debuted a new restaurant, The Corner, a taproom and oyster bar, downtown. However, the Galveston kingpin had little time to enjoy it. The next year, stricken with cancer in his digestive tract, he traveled to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore where he died from complications of surgery.

In a case of better late than never, merely weeks after his death, the Texas statehouse launched a probe of Sam’s financial interests and subpoenaed Rose and others to testify. It turned out that the Maceos ran the largest illegal gambling operation in Texas. Lawmakers reported the men grossed $5.6 million (about $60 million in 2021 dollars) from 1949 to 1950 alone, $4.6 million from illegal gaming – dice games, tip books, bingo, 500 slot machines and five bookie venues. They employed 600 people with a $1 million payroll.

The director of public safety for Texas, Colonel Homer Garrison Jr., remarked, more than somewhat after the fact, “The people there (in Galveston) seem to think because they live on an island they are immune from the laws of the state.”

It still took some time for officials to act. New Texas laws soon made operating slot machines a felony and prohibited telephone companies from servicing bookie joints.

Rose died in 1954. The Maceo empire finally unraveled in 1957, amid a state crackdown on illegal gambling. Anthony and Vic Fertitta, new owners of the venerable Balinese Room (and related to the Maceos via marriage), sold the club. Anthony Fertitta then left for Las Vegas, where he worked as a greeter at the El Rancho Vegas. Fertitta’s family would later build a casino empire of their own in Las Vegas.

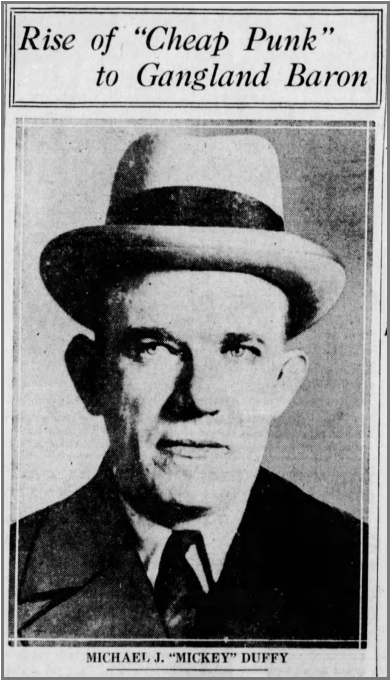

Mickey Duffy

It was a classic Hollywood-style gangster attack. On February 25, 1927, during the criminal heyday of Prohibition, Mickey Duffy, touted as the boss of beer, vice and extortion from New Jersey to eastern Pennsylvania, was leaving his nightclub in Philadelphia with his wife, Edith, and a bodyguard.

Suddenly, a large sedan sped by and a gunman inside unleashed a burst from a Thompson submachine gun toward Duffy, wounding him five times. His bodyguard died on the spot. A doorman was seriously injured. Duffy’s wife had entered their car before the fusillade. In critical condition at a hospital, Duffy survived.

Duffy, however, had only four years to live, when other gangland shooters would win out. By then the couple had been living in the lap of luxury, from his bootlegging sales, in top-flight hotel suites and an expensive “modernist” home in the tony “blue blood” Philadelphia suburb of Overbrook. The Philadelphia Inquirer stated that before Duffy’s violent death in 1931, he “held South Jersey’s beer and other rackets in the palm of his hand.”

He was the son of immigrants from Poland — his real name was Michael J. Cusick, but he chose an Irish pseudonym — and spoke and read Polish. He came up the hard way, as a violent criminal with 28 arrests going back to 1908, including suspicion of robbery, assault and battery, larceny, breaking and entering, burglary and attempted murder.

In a county jail in New York for petty larceny in 1916, he escaped until his capture in Philadelphia a year later. In 1919, a judge sentenced him to three years in Pennsylvania state prison for aggravated assault and battery with intent to kill, carrying concealed weapons and assault with intent to steal.

Out of prison in 1922, Duffy struggled again, not learning from his past. He promptly got himself arrested for another alleged robbery and assault and battery, but got off.

In 1924, he racked up still more arrests for alleged possession of illegal liquor, a jewelry robbery and assaulting a police officer. Duffy cajoled and beat his way into the policy numbers racket until he lost money and turned to bootlegging beer. He acquired illicit breweries in Camden and Egg Harbor, sold his suds in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and held pieces of some area speakeasies.

That year, he opened his own cabaret and dance cafe, the Club Cadix, in a chic part of downtown Philly. As of 1925, police did not arrest him, likely a result of his cash payoffs. A grand jury in Philadelphia in 1928 described Duffy as the “King of Racketville,” but it did not charge him either. Wealthy and arrogant, Duffy and partner Harry Mercer embarked on an extortion racket, targeting drivers of trucks delivering illegal liquor, forcing from them “protection” payments to avoid attacks from his henchmen.

Meantime, Duffy and Edith moved to their new $65,000 Spanish villa-style home — which some of his pals claimed he bought with 65 $1,000 bills — and spent $50,000 more on luxury furnishings. The abode sported an ornate interior, cactus garden, talking parrots, a modern electrical alarm system and staff of armed guards. They bought several large new cars. He purchased Edith a diamond solitaire ring and a $30,000 bracelet. He lavished more money on outlandish “snappy” clothes and “liked to refer himself as a modern Beau Brummel,” as the Inquirer put it. The Duffys vacationed in Florida and lived for weeks on end in suites of expensive hotels, such as Philadelphia’s Ritz-Carlton at $1,000 a week (about $18,000 in 2021 dollars).

As of 1930, he was pulling in $10,000 a week and had $500,000 in the bank. He made sure to pay his federal taxes. Still, Duffy felt insecure as an ex-con and gangster and tried to rehabilitate himself within the law-abiding community. He donated to charities and their church. But it didn’t work. An orphanage denied the couple’s request to adopt a child.

On the last days of his life in summer 1931, Duffy told police of seeing strangers hanging around his property. He checked into the Ambassador Hotel in Atlantic City, hired two heavily armed bodyguards and never left the hotel alone. He started injecting himself with morphine to ease his nerves.

On August 30, 1931, at the hotel, Duffy met with his lawyer, then-U.S. Congressman Benjamin Golder, to discuss his upcoming truck racketeering trial, set for September 14. That early afternoon, he allowed two men to have lunch with him in his fourth-floor suite. Afterward, he crawled into bed for a nap. But the men returned and quietly fired several shots into his head as he slept. They escaped unseen.

Duffy’s funeral at his extravagant home drew about 3,000 onlookers. He left Edith $400,000 cash plus $150,000 in property. Who killed him remained a mystery until 1935, following an inquiry by the Pennsylvania Bar Association into underworld corruption among lawyers and police. Philadelphia Police detective James Ryan concluded that two of Duffy’s trusted henchmen, Sammy Grossman and Al Skali, killed their boss to take over the beer racket. But soon, Grossman and Skali became “too cocky” as beer overlords of a competing gang in New York, the 69th Street Mob. The 69th gang sent hitmen to kill both men a few months after Duffy’s demise, and took over their beer business.

George and Nettie Martin, “The Martin Gang”

In August 1934, nine months after the end of Prohibition, Nettie H. Martin applied for a license in Baltimore, Maryland, to serve wine, beer and hard liquor at her new restaurant downtown. Maybe she appreciated the irony. Or, she finally learned her lesson, from arrests and jail meted out to her and her husband, George, as leaders of the Martin Gang.

Nettie, a former beauty shop owner, and George, a one-time used car lot owner, were among the early organized outlaws of Prohibition, even in 1919, before the official ban on producing, buying or transporting liquor went into effect in 1920. The first reports came from officials in Virginia, who wondered about a “mysterious blonde” woman associated with illicit liquor trafficking along the Richmond Highway.

The Martin band of bonded whiskey thieves, led by George, attracted real attention in 1921. The Martins were part of a so-called “Bootlegger’s Trust” consisting of five large liquor-stealing and dealing gangs. The trust maintained a pool of savvy lawyers to represent the gangsters in court, a crew of experienced rumrunners and a fleet of vehicles to transport pinched legal whiskey. Their thefts stretched from Virginia and Maryland to Washington, D.C., Pennsylvania and New York.

On September 9, 1921, George, 34, and Nettie, 24, and their associates raided the Outerbridge Horsey bonded distillery in Burkittsville, Maryland. About 15 gang members and a half-dozen trucks arrived. George and several men dressed as federal Prohibition agents flashed badges to make the security guard feel at ease. Then George put a pistol in the guard’s face and they proceeded to remove 1,100 cases of whiskey worth about $200,000 ($3 million in 2021 dollars). While George tied up the guard, Nettie used pencil and paper to check off the barrels the gang loaded into trucks. Later, a barn owner three miles away told police that after George compelled him to house the stolen liquor, Nettie supervised the unloading.

George and Nettie were arrested and among 10 gang members indicted in the robbery. Attorneys for the Bootlegger’s Trust’s got the court to drop the charges against Nettie, and gained an acquittal for George.

U.S. prosecutors then suspected the Martin Gang when 20 bandits stole $75,000 in whiskey from the Standard Distillery in Baltimore by siphoning the liquor out of barrels. They also held the gang responsible for a robbery at the Gwynnbrook booze plant in Baltimore and the Foust Sons Distillery in Glen Rock, Pennsylvania.

In one account, police reported that Nettie helped a couple of drunken liquor thieves, who had veered off the road. Nettie removed two cases of whiskey from the trunk of the disabled car before police arrived, bailed the men out of jail and returned the whiskey to them.

In late 1922, George’s fortunes went south when he racked up his sixth arrest. Federal officers took him and Nettie to jail in the Foust raid. That November, while at a federal office, George assaulted U.S. investigator (and later famed undercover agent) Michael F. Malone after Malone’s efforts resulted in George’s indictment in the Foust robbery. George received 30 days behind bars for the assault.

Newspapers noted that the feds nicknamed Nettie the “queen of the bootleggers” for her roles in the Foust robbery and raids on six other distilleries resulting in $500,000 (about $8.2 million in 2021) worth of liquor.

Frustrated Prohibition agents marveled at Nettie’s scheming and driving ability. At one point in 1922, according to the Harrisburg Telegraph, as George fought off officers attempting to arrest him, Nettie “who is a very daredevil driver, stepped on the gas in a crowded street and made a clean getaway.”

George plotted the theft strategies while Nettie scouted out places to rob, the best routes to maneuver whiskey-loaded trucks between Baltimore and Washington and aided the gang in eluding police and dry agents.

“Dashing at high speeds across the borderline of Maryland and Washington, the ‘mystery woman’ succeeded in escaping the police dragnet and safely landed liquor into the hands of whiskey rings, it is alleged,” reported the York Dispatch in December 1922.

While in court after Nettie’s arrest in the Foust case that December in Harrisburg, Maryland, a reporter labeled her a “young petite, pretty blonde of the flapper type” who was “dressed in a sports costume and flashed a big cluster diamond ring.” George’s unfortunate nickname in the news was “Monkey Face.”

George received the brunt of the law. In 1926, a federal court convicted him of robbery and conspiracy in the Standard Distillery raid and, after a long trial, sentenced him to two years in prison.

Nettie waited for him and remained his devoted partner in crime. The depleted Martin Gang came alive briefly in December 1928, when the not-rehabilitated George tried to rob a truck in Pennsylvania of U.S.-approved liquor headed for consumption by diplomats in Washington.

Nettie tried to bribe the truck driver not to testify. In the end, George got five years in prison for assault to rob, and Nettie 30 days for obstructing justice.

Both faded into obscurity. But Nettie determined to go straight post-Prohibition with a license to buy and sell liquor, legally, at 117 N. Eutaw Street, Baltimore. Today it serves as the site of the Eutaw Liquor Store.

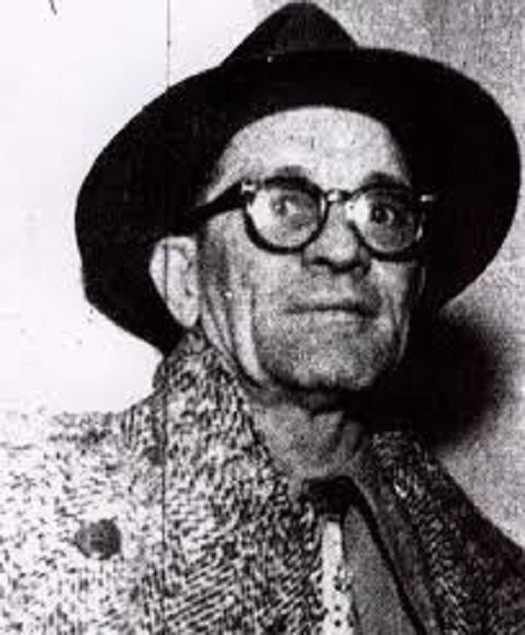

Theodore Roe

Shortly before 11 p.m. on August 4, 1952, Theodore “Teddy” Roe, numbers gambling boss of Chicago’s South Side, was about to enter his car outside his Michigan Avenue apartment when someone yelled his name. After he turned, two men fired five blasts from 12-gauge shotguns at him. Hit by double-o pellets in the head and chest, Roe died at a local hospital.

Three days later, a crowd estimated at more than 6,500 showed up for the funeral at a church on Wabash Avenue and thousands more walked past the $5,000 open casket of the wealthy man known as “Robin Hood” for his many donations, gifts and small loans to his employees that he regularly forgave.

No sooner had the burial ended than Chicago Police drew controversy by arresting his five pallbearers to furnish information to help solve the case. More interestingly at the time, 15 or so hoodlums were also arrested for questioning — a Who’s Who of the Chicago Outfit, including Anthony Accardo, Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik, Sam “Golf Bag” Hunt, Sam Giancana, Sam Battaglia, Leonard Gianola and Marshall Caifano. But the murder inquiries never produced any chargeable suspects.

Homicide detectives figured Roe’s rubout had to do with the Outfit’s longtime goal to take over the predominantly black South Side’s illegal policy wheel business from African-American kingpins such as Roe (who, ironically, was half-Italian). While other policy bosses, black and white, gave in to the Outfit’s intimidation and surrendered their businesses, Roe stridently resisted, even challenged the hoods to come get him. He hired some ex-cops as bodyguards and carried a loaded .38-caliber pistol with extra shells.

As equal partners in one of the 16 or 17 big numbers rackets in the South Side, Roe, Edward P. Jones and three other partners netted $4.9 million from 1945 to 1950, employing 70 people plus 300 bet writers on commission. The partners’ net profits hit a height of $1.1 million in 1946.

Jones had led their policy game (illegal by Illinois law since 1905) in the 1930s. Back during Prohibition in the 1920s, Outfit chief Al Capone made a deal with South Side racketeers, ceding control of policy gambling in exchange for not competing in the beer racket.

Jones himself broke the rules of the street by associating with the Outfit, more often than accounts that paint him as a blameless dupe of the Mob. While he and Giancana served time together in an Illinois state prison in 1939, Jones is said to have told Giancana how his policy wheel worked to lure South Siders to lay their mostly fruitless nickel, dime and quarter wagers.

In the early 1940s, Giancana and the Outfit, based on the West Side, set their sights on the South Side policy racket, the only illegal gambling scheme left in the city that they did not command. A study by Illinois officials found that the South Side ran at least 66 policy games and operators paid about $25,000 a week in protection money to police and politicians.

After his release from prison, Jones tried to negotiate an investment deal with Giancana to buy 2,000 jukeboxes from the Outfit to place in South Side locations. Meanwhile, Chicago Mayor Edward Kelly’s Democratic Party political machine, on the receiving end of millions in gambling profits from the Outfit, allowed the gang to have its way in vice, at Jones’ expense. The numbers games employed many hundreds in Chicago’s Black communities. Nevertheless, Jones lost credibility among some South Side residents for dealing with white gangsters.

In May 1946, Giancana, desiring to wrest control, had his goons kidnap Jones and hold him for a $250,000 ransom. Roe negotiated that down to $100,000 and assisted in raising the money for Jones’ release. Intimidated, and with a grand jury investigation on the city’s policy racket looming, Jones and his brother George fled to an estate they owned in Mexico.

Roe took over as boss of the Maine-Idaho-Ohio policy game and wired shares of the profits to partners Edward and George in Mexico. Roe used the South Side’s Boston Club as his roost of operations. The club also ran casino games. Roe and his partners often used their profits to invest in real estate and other legitimate businesses.

Top members of the Outfit approved Giancana’s plan to muscle in on Roe’s policy racket. Basking in the successful Jones kidnapping, Giancana made Roe their next victim.

That September 7, several gangsters stormed the Boston Club and fired shots at Roe, but he escaped unhurt and continued to run his games. The Outfit would terrorize other policy racketeers, ousting the Italian-American Benvenuti brothers — Julius, Caesar and Leo — after bombing their homes. “Big Jim” Martin, policy chief of a mostly Black part of the West Side, gave up when gangsters sprayed his car with bullets.

In Chicago in December 1950, both Roe and Edward Jones testified openly before the U.S. Senate’s Kefauver Committee. Roe answered in remarkable detail how his policy business worked. He said they made $12,000 per game, drew two games a day and that about 60 percent of Black South Side residents played regularly. Their year-by-year tax reports, entered into the Senate record, revealed their net profits of nearly $5 million from 1945 to 1950.

Seven months later, on June 18, 1951, four armed men blocked Roe’s car on a South Side street. In a gun battle with Roe and a bodyguard, Leonard “Fat Lenny” Caifano, a higher-up in the syndicate, was shot through the head and killed and another gunman wounded. Police could not figure if Roe or the bodyguard shot Caifano as the bullet went missing. Meanwhile, Roe, under arrest, claimed self-defense against a kidnapping, and a jury acquitted him of murder charges. The shooting of an Outfit torpedo made Roe a neighborhood hero.

After the end came for Roe in 1952, his death attracted widespread outrage in the South Side’s Black community. But once the Outfit grabbed his policy racket, the gang employed local people in the business, made Capone-like charitable donations and succeeded in currying favor among game players.

Within a couple of years, citywide policy games became the Outfit’s most profitable racket, with a net estimated at $150 million per year.

No one was ever charged in Roe’s murder. However, in 1958, before the U.S. Senate’s Rackets Committee, Chicago Police Lieutenant Joseph Morris testified he believed members of the “Young Bloods” faction of the Outfit were responsible for Roe’s killing. Those in the group included Giancana, Caifano (Fat Lenny’s brother), Battaglia and William “Smokes” Aloisio.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org