The world’s top 5 cybercrime schemes

A new breed of organized crime targets anyone with a web connection

Last year a ransomware gang took control of the networks of two major casino corporations in Las Vegas. Caesars Entertainment reportedly paid the $15 million ransom, while MGM Resorts did not, resulting in losses of $100 million while it worked to regain control.

The September 2023 cyberattack was not an isolated incident. According to a 2023 report, there were 3,205 data compromises in the United States, affecting more than 350 million people. In today’s digital world, anyone with a connected device can become a victim of cybercrime.

While extortion via ransomware is the most prevalent form of cybercrime, other types of crime have moved online, too. Bank heists, drug empires and human trafficking are all elements found in the internet underworld. The scale of these crimes ranges from single-person operations to state-sponsored cybergangs.

Here we explore criminals who fit the organized crime bill, motivated at least in part by financial gain. Not included are people, such as infamous hacker Kevin Mitnick, who commit cybercrimes just to see if they can. Neither are the so-called “hacktivists,” such as Anonymous, who create digital disruptions to further a cause. Instead, criminals on this list have racketeered in ways straight out of the Mob’s playbook.

5. Joseph Popp and the first ransomware

With every new technology comes new ways to commit crime. Malware, short for malicious software, has been around since Intel made the first microprocessor widely available to consumers in 1971. While most were nuisances with hidden messages or mild annoyances, the late 1980s saw an increase in destructive malware. In 1989, a new kind of malware emerged: ransomware.

Ransomware typically comes in the form of a Trojan horse, a type of malware disguised as legitimate software. Like viruses, Trojans cannot automatically infect a computer. A human must interact with them to function, such as clicking a link, downloading a file or inserting a USB drive or its precursor, a floppy disk.

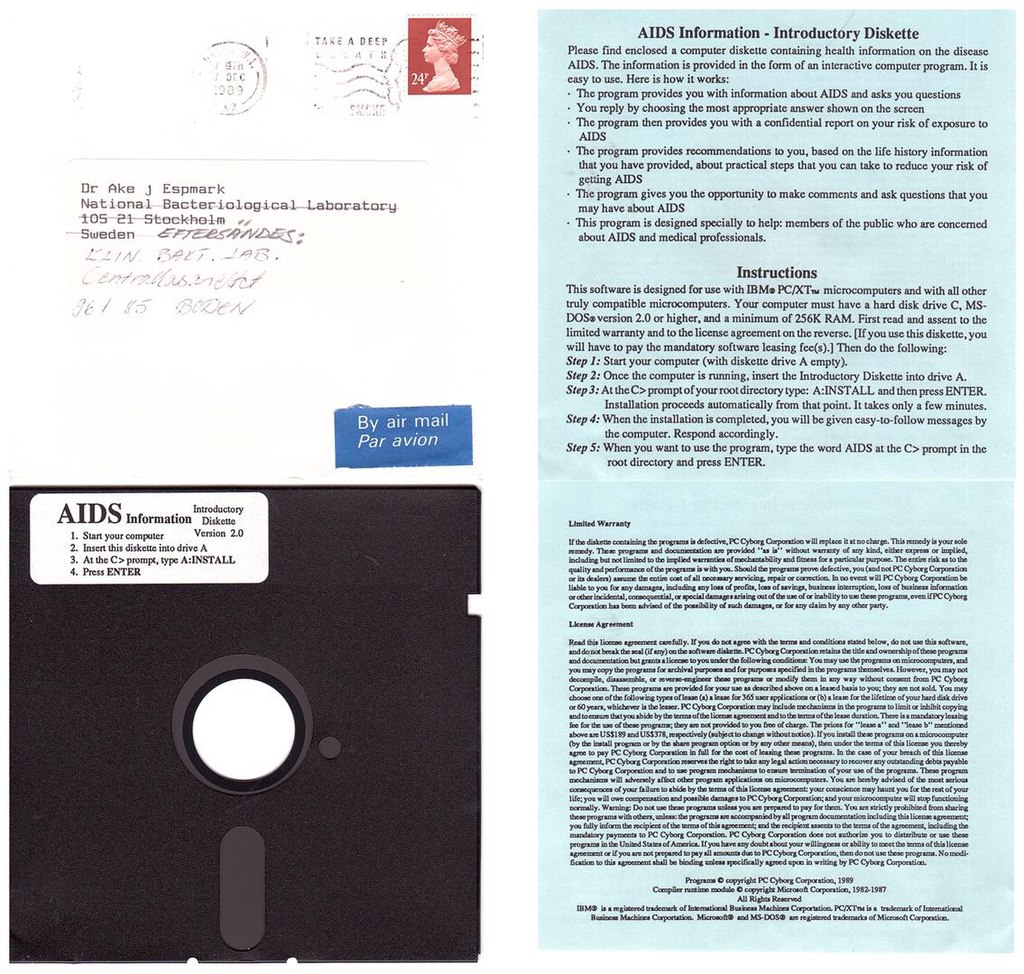

In December 1989, thousands of Europeans received a floppy disk in the mail, labeled “AIDS Information Introductory Diskette Version 2.0.” The recipients were either tech magazine subscribers or attendees of the 4th International Conference on AIDS in Stockholm, Sweden. Those who installed the software found a simple questionnaire that assessed the user’s risk of contracting HIV. Underwhelmed, users closed the program and forgot about it – until 90 startups later.

Upon the 90th time booting up the PC, a new message appeared: “It is time to pay for your software lease from PC Cyborg Corporation. Complete the INVOICE and attach payment for the lease option of your choice.” The message concluded with instructions to send $189 to a P.O. box in Panama. It’s not uncommon for software to ask for money to keep using it, but this one prevented users from accessing the rest of their files.

Eddy Willems, a systems analyst for an insurance company at the time, was one of the victims who received a disk — now framed in his living room. He quickly figured out how the program worked and reversed the encryption, but others weren’t so savvy. In a panic, some victims wiped their hard drives, which got rid of the malware — and their data, too. Around the same time that Willems was sharing his solution, the January 1990 issue of Virus Bulletin, an international newsletter, offered free disks with programs to remove the AIDS Trojan and recover encrypted files.

Law enforcement traced the Panamanian P.O. box to a Harvard-educated anthropologist and World Health Organization consultant named Joseph Popp. Popp had returned to the United States after an apparent nervous breakdown at a Nairobi AIDS seminar upon learning that his AIDS Trojan was making international news. On February 1, 1990, the FBI arrested Popp at his parents’ home in Willowick, Ohio, and he was extradited to the U.K. to face blackmail charges.

British courts ruled Popp “was mentally unfit to stand trial” and sent him back to the United States. Scotland Yard officials reported he had been “wearing hair curlers in his beard and a box around his waist” that he believed “could detect radiation.” Popp’s increasing paranoia also led him to believe that Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega was trying to kill him. An Italian court sentenced him in absentia to two and a half years in prison, but the U.S. declined to extradite him.

Popp acted alone, but his ransomware scheme inspired a trend in organized crime that is still thriving today.

4. Silk Road and “Dread Pirate Roberts”

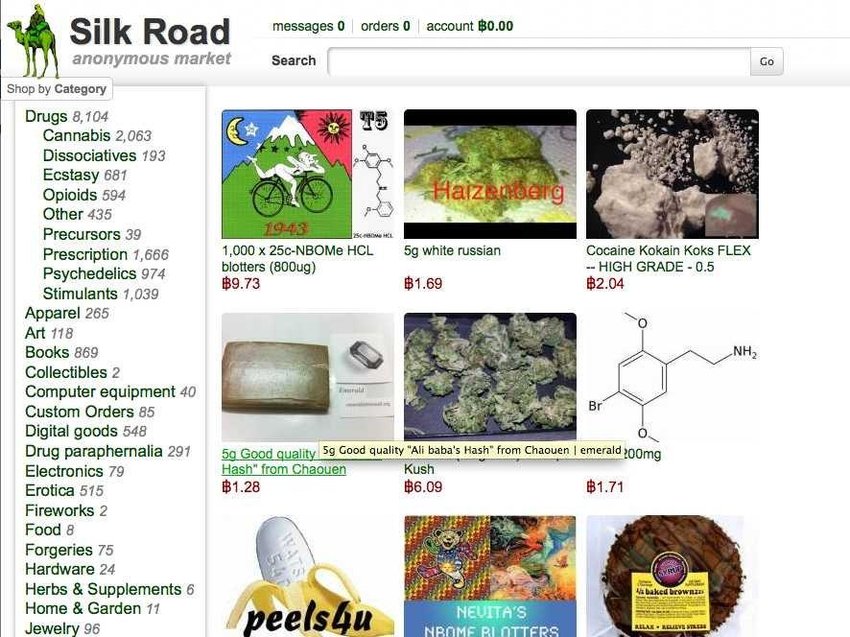

In 2010, struggling entrepreneur Ross Ulbricht began working on a side business, a website where “people could buy anything anonymously, with no trail whatsoever that could lead back to them,” according to his digital journal entries. Drugs were part of his business model from the beginning. Ulbricht grew psychedelic mushrooms to sell on his new marketplace, which he called Silk Road.

On June 1, 2011, an article on the gossip blog Gawker thrust Silk Road into the spotlight. This was a pivotal moment for the dark web marketplace, both in terms of growth and notoriety. After the article was released, New York Senator Chuck Schumer called for law enforcement to shut down Silk Road.

Silk Road was only accessible through Tor, an anonymous web browser that prioritizes privacy above all else. Originally conceived by the U.S. Navy, “the onion routing” browser adds enough layers of encryption to mask a user’s web traffic and is a prerequisite for accessing the dark web. Silk Road added another layer of anonymity by having Bitcoin as the only method of payment.

Ulbricht enjoyed anonymity as the owner of Silk Road, known to the public only by his handle, “Dread Pirate Roberts.” Perhaps by using that name, an inherited title from the film and novel The Princess Bride, Ulbricht believed he had plausible deniability. During an extended interview with Forbes journalist Andy Greenberg in July 2013, Ulbricht, under his pseudonym, claimed he was not the first administrator of Silk Road nor the first to use that name. Ulbricht boasted he was confident his security measures prevented law enforcement from closing in on him. He was wrong.

Undercover federal agents had already breached Ulbricht’s operation, posing as drug dealers and impersonating a Silk Road moderator whose account had been seized. He had also revealed his identity when using his personal email address to recruit staff on a Bitcoin forum.

On October 1, 2013, Ulbricht was sitting at a table in a San Francisco library when he received an urgent message from the seized moderator account. After logging into Silk Road, a nearby couple began fighting. As he turned to look, a woman snatched his laptop while a man grabbed him. What Ulbricht didn’t know was that everyone around him, including the bickering couple, were federal agents. They had to catch him by surprise, with his laptop open, to get past his computer’s encryption. Federal law enforcement soon took over Silk Road, replacing it with the now familiar notice, “THIS HIDDEN SITE HAS BEEN SEIZED.”

Ulbricht was convicted on seven counts related to operating Silk Road. His “Dread Pirate Roberts” defense did not convince the jury. In May 2015, he received two life sentences plus 40 years without the possibility of parole. A group of his supporters, who run the website freeross.org, argued that his sentence was excessive for nonviolent charges (a murder-for-hire charge was dropped after his sentencing). In May 2024, then-former President Donald Trump pledged to commute Ulbricht’s sentence if re-elected.

3. The Lazarus Group

On November 14, 2014, employees at Sony Pictures logged into their company’s network to find doctored images of the severed heads of two Sony executives and gunshot sounds coming from their speakers. The shocking images were accompanied by a strange message and a threat: “If you don’t obey us, we’ll release data shown below to the world. Determine what will you do till November the 24th.” The executives depicted received a similar warning a few days earlier.

At the same time, malware began erasing data across Sony’s network and making systems inoperable. Sony had to take its network offline, which would take weeks to repair, but there was worse to come. The hackers publicly released the personal information, private emails and internal copies of movies and scripts to the internet, devastating Sony’s reputation, morale and profits. Who could have been motivated enough to carry out such a destructive cyberattack against an entertainment company?

The casus belli for the hackers was The Interview, a 2014 comedy film by Sony Pictures. The political satire stars James Franco and Seth Rogen as a reporter and his producer tasked by the CIA to assassinate North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. After the trailer was released in June 2014, the North Korean government decried the movie as an “act of war.” Sony responded by toning down the film’s violence but otherwise cautiously allowed the movie to proceed. Rogen, also a director of the movie, was unmoved by the threats, writing on Twitter: “People don’t usually wanna kill me for one of my movies until after they’ve paid 12 bucks for it.” After the cyberattack, however, Sony canceled the film’s release before allowing a very limited theatrical release — major theater chains opted not to show the film for fear of violence — alongside a digital release on streaming platforms.

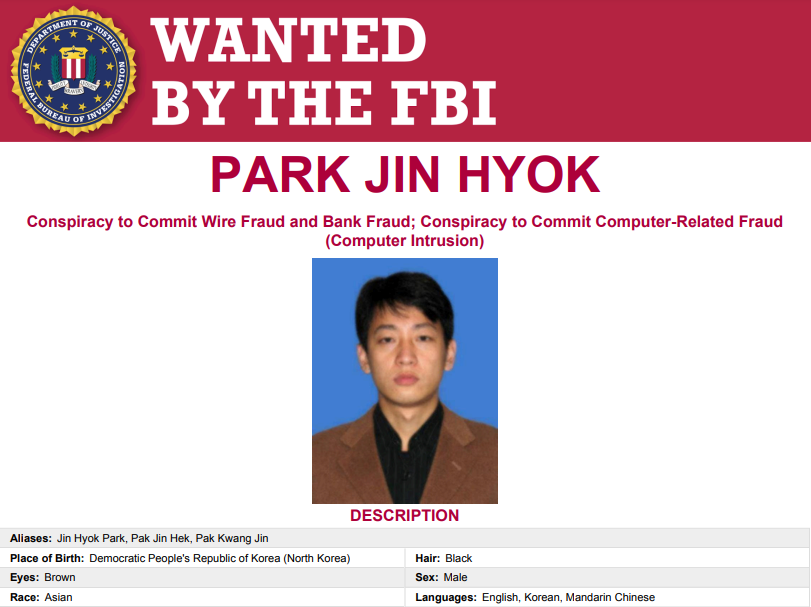

On December 19, 2014, the FBI formally blamed North Korea for the cyberattack. Analysis of the malware revealed similarities to other attacks by North Korean threat actors, including the 2013 cyberattacks on South Korean media companies and banks. Although they called themselves the “Guardians of Peace” in the Sony Pictures attack, the cybersecurity community labeled them the “Lazarus Group” for their ability to vanish and reappear with a new identity in each attack.

The Lazarus Group has an extensive rap sheet beyond the Sony Pictures cyberattack. In February 2016, the state-sponsored hackers attempted to steal nearly $1 billion from the Bangladesh Bank via its New York Federal Reserve account. While authorities stopped or intercepted most of the transfers, the Lazarus Group got away with $81 million, making it one of the largest bank heists in the world. They are also suspected of engineering the WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017, which infected more than 300,000 computers worldwide.

This year, a United Nations report on North Korean cyberattacks between 2017 and 2023 put the amount of money stolen at $3 billion, with a quarter of that in 2023 alone. The plunder funds North Korea’s technology and military programs, including nuclear weapons.

2. Pig-butchering rings

In August 2024, Heartland Tri-State Bank CEO Shan Hanes was sentenced to more than 24 years in federal prison for embezzling $47 million from the bank, which failed as a result. The stolen money, which included funds from a local church and his daughter’s college savings, went to a cryptocurrency wallet that belonged to someone he had been communicating with since 2023 on What’s App, a popular instant messaging service. This person, whose identity is still unknown, convinced Hanes to send bigger and bigger investments for a cryptocurrency scheme that would never pay out.

The scam is called “pig butchering.” It begins with a contact through a dating app, social media or even a wrong-number text message. The scammer builds trust with flattering comments, attractive “selfies” and meetup proposals. The conversation inevitably turns to how much success they’ve found investing in cryptocurrency. If the target doesn’t have a cryptocurrency wallet, their “new friend” helps them set it up on a legitimate cryptocurrency exchange.

The scammer continues the ruse for weeks, even months, “fattening up” their victim until it’s time for the “slaughter.” They instruct the target to send money to a crypto wallet or download a fake crypto app, starting off with small amounts but gradually ramping up to life savings-draining investments. The fake apps show the victims having successful returns on their investments, and even allow the victims to withdraw money. But once the scammers have received as much money as they can get from the victim, they cut and run.

When the Covid-19 pandemic shut down international tourism, Chinese organized crime groups turned to pig butchering as a new source of income to make up for the lack of gambling tourists. However, there’s something even more sinister happening behind the scenes.

The person on the other side of the messaging app is often a victim as well. CNN reported last December about an Indian man who moved to Thailand for a promising IT job, but when he got there, his new employers smuggled him into Myanmar and confiscated his passport. They trained him to be a scammer, forced to coerce targets by posing as a blond woman. If he didn’t cooperate, he would be jailed, beaten, tortured or worse.

KK Park, a facility in Myawaddy, Myanmar, is one of the compounds engaged in modern slavery. While the trafficked workers are forced to scam, their families are ransomed for their loved ones’ freedom. Unproductive workers are sold to other compounds and their ransoms increased. In a 2024 report, the United Nations estimated that at least 300,000 people are held against their will at labor camps in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. Political leaders in these countries are passive, at best, in combating these compounds. In Cambodia, law enforcement may help people who escape but otherwise allow the labor camps to continue operating.

1. ALPHV/BlackCat

For this last entry, we return to last year’s cyberattack in Las Vegas. In August 2023, MGM’s IT help desk received a call from an employee who needed a new password. MGM staff only had to provide their name, employee ID number and date of birth for a password reset. However, the caller was not the actual employee — they used information publicly available on LinkedIn to impersonate them. By the time the real employee reported the password reset notification to MGM security, the hackers had already gained access.

MGM tried to mitigate the damage by shutting down its systems, which conspicuously disrupted slot machines and prevented reservations. However, the ransomware was already in place, stealing their data and locking them out. Around the same time, Caesars Entertainment was going through a similar ordeal.

The attacks that crippled two of Las Vegas’ largest resort corporations only took a 10-minute phone call. Manipulating people into performing an action or divulging information, called social engineering, is one of the most effective skills in the hacker’s toolkit. Aspiring cybercriminals no longer need to have coding skills for a successful infiltration.

Two groups are attributed to this cyberattack: ALPHV/BlackCat and Scattered Spider. The world of extortion-related cybercrime has a business model: ransomware as a service (RaaS). Ransomware operators, such as ALPHV/BlackCat, create the extortion software and offer it through subscription models or affiliate programs. According to cybersecurity company CrowdStrike, the operators also create payment portals for victims to pay ransoms, offer tech support and help with ransom negotiations. Scattered Spider, an affiliate, carried out the attack using ALPHV/BlackCat’s software, which features an icon of a black cat.

In December 2023, the Justice Department announced it had disrupted ALPHV/BlackCat’s operation, taking over its website with the familiar notice, “THIS WEBSITE HAS BEEN SEIZED.” The takedown screen was replaced hours later with “THIS WEBSITE HAS BEEN UNSEIZED” after the criminals apparently recovered their website. The FBI, however, had retrieved decryption keys that helped more than 500 organizations regain their data, saving them a collective $68 million in ransom payouts.

Last March, the seizure announcement again appeared on ALPHV/BlackCat’s website. But law enforcement claimed to have had nothing to do with the alleged takedown. Furthermore, evidence that the seizure announcement was a fake was found in the website’s source code. Cybersecurity experts reported this was an exit scam, a way to cash out without having to pay what they owed to their affiliates.

The fight against cybercrime is often a game of whack-a-mole. A new ransomware platform, Cicada3301, emerged in June 2024 that some cybersecurity experts have noted is very similar to ALPHV/BlackCat. Although it could be that ALPHV/BlackCat sold its code to a new group, it also wouldn’t be the first time the hackers have reappeared under a different name. The FBI has linked the group as a successor to DarkSide, a ransomware operator responsible for the 2021 Colonial Pipeline attack that cause gasoline shortages in the South.

While the hackers behind ALPHV/BlackCat disappeared into the shadows, members of Scattered Spider were not so lucky. Several arrests were made this year of individuals allegedly connected to the group, including an unnamed 17-year-old teen in the United Kingdom. One of the suspected members, Noah Michael Urban, a 19-year-old whose online identity is “King Bob,” was arrested in Florida and linked with stealing more than $800,000 in cryptocurrency scams.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org