The inspiring rise and tragic fall of the ‘Italian Sherlock Holmes’

Celebrated New York detective Joseph Petrosino murdered in Sicily 110 years ago this week

On the evening of March 12, 1909, New York Police Department detective Joseph Petrosino left his hotel on the east side of the Piazza Marina in Palermo, Sicily. He walked to the Café Oreto for dinner. He ordered pasta with marinara sauce, fish, fried potatoes, cheese, peppers and fruit. He also had wine. After dinner, he paid his bill and left the restaurant.

As Petrosino walked across the square, which was almost deserted, two men suddenly appeared and started shooting. They fired four rounds. Three of them hit Petrosino, who lay on the sidewalk, dead, with the murder weapon, a revolver, nearby.

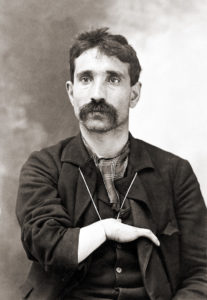

One of the most famous law enforcement officers in the world, the “Italian Sherlock Holmes” who battled evil on the streets of New York and who did as much as anyone to enhance the reputation of Italian Americans up to that time, was assassinated in the line of duty.

It was 110 years ago this week that Joseph Petrosino met his demise, but his groundbreaking and storied career remains a permanent and important chapter in the epic history of law enforcement’s battle with organized crime.

Early years in America

Born in 1860 in Padula, Italy, Giuseppe Petrosino migrated to the United States with his parents and siblings when he was 13 years old. The family settled in Manhattan, in the neighborhood that would become known as Little Italy. The teenager soon learned English and went to work to support his family. He and a friend established a newspaper and shoe shine stand at 300 Mulberry Street in front of what was then the headquarters of the New York Police Department.

But Joe Petrosino had ambitions to rise above the bottom rungs of the economic ladder. He tried out a range of jobs over the next few years until he secured a position as a street cleaner. As Stephan Talty notes in The Black Hand: The Epic War Between a Brilliant Detective and the Deadliest Secret Society in American History, “It didn’t sound like much of an advancement, but at the time, the city’s sanitation department was run by the New York Police Department. For the right kind of immigrant, it could be a stepping-stone to greater things.”

And so it was for Petrosino. He dutifully pushed a three-wheeled cart through the streets of New York and swept the streets of grime, litter and horse manure. His hard work paid off with a promotion: He took charge of the boat that hauled the city’s garbage out into the Atlantic Ocean to be dumped.

Joining the force

Petrosino’s work caught the attention of a New York Police inspector named Aleck “Clubber” Williams, one of the most powerful, feared — and corrupt — officers in NYPD history. Williams wanted Petrosino to join the police department, but there was a problem: At 5 feet 3 inches tall, Petrosino was four inches too short to qualify for the job. Nonetheless, Williams lobbied on Petrosino’s behalf, and the 23-year-old became an officer in 1883. His shield number was 285.

The New York police force was largely Irish American at the time, and Petrosino was one of its first Italian American officers. This created challenges for Petrosino, but it was worse on the streets of Little Italy, where, to a large portion of the Sicilian-born population, a man in uniform was seen as an enemy.

“There were many Italians who felt differently, who knew that Italian policemen were badly needed in the colony and were proud of Petrosino’s achievement,” Talty writes. “But others sent him a constant stream of menacing letters, letters that became so alarming Petrosino was forced to look for another place to live.”

Petrosino gained a reputation as tough and incorruptible. Police work in those days involved plenty of street fighting, and Petrosino was incredibly strong if not tall. Despite being a good policeman, Petrosino was not likely to rise within the Irish-dominated hierarchy of the NYPD.

Enter TR

But then another supporter emerged. In 1895, Theodore Roosevelt became chairman of the New York Board of Police Commissioners. Consistent with his later reputation as U.S. president, Roosevelt was a reformer. He was determined to root out corruption in the department and professionalize police work. Recognizing a need to address crime in Italian American neighborhoods, Roosevelt soon made Petrosino a detective sergeant.

Petrosino took full advantage of the opportunity. He relished detective work. He wore an array of disguises to infiltrate criminal enterprises. Rather than keeping extensive files, he memorized names, faces and details, developing an encyclopedic knowledge of New York’s criminal element. His success at busting rackets and bringing criminals to justice made him famous. Newsmen began calling him the “Italian Sherlock Holmes.”

Black Hand Society

After the turn of the century, Petrosino spent more time pursuing Black Hand extortionists than any other type of criminals. The Black Hand was a secret society of Italians who threatened to kidnap children, blow up homes or kill their fellow Italians if they did not pay a prescribed ransom by a certain time. Black Hand letters typically were illustrated with images of daggers and black crosses. The extortionists were successful because they often did exactly what they threatened to those who refused to pay.

Black Handers were not limited to New York. They were operating all over the country in the early part of the 20th century. Some Black Handers fell under the control of Mafia bosses, while others operated independently.

Italian Squad

If Petrosino was going to put a dent in the Black Hand problem in New York, he would need help. At first, the NYPD brass was indifferent to the issue of Italians hurting other Italians. Petrosino went to the press, calling for the department to establish a team of detectives, an “Italian Squad,” to take down the Black Hand. Finally, in 1904, the department agreed to create an Italian Squad — but with five men, not the 20 Petrosino had requested.

Petrosino searched throughout the NYPD ranks and found five officers who could speak Italian. The Italian Squad initially was not given an office out of which to operate. Petrosino’s apartment served as the squad’s first headquarters.

As Italian immigration to the United States soared, and Black Handers along with it, the Italian Squad worked day and night to try to get a handle on the epidemic. It was an uphill battle, to say the least. But Petrosino and his men arrested hundreds of Black Handers. Their success convinced the NYPD to expand the Italian Squad. Petrosino had 40 men by 1906.

Still, even with more men, Petrosino was not able to eliminate the Black Hand. By 1907, “the Italian Squad was still catching and arresting Black Handers throughout the city, and driving out others through intimidation, but it seemed that for every Black Hand member the squad caught, three new ones joined the Society,” Talty writes.

Trip to Sicily

Police Commissioner Theodore Bingham had an idea. The members of the Italian Squad being too well known, he wanted to create a “secret service” of half a dozen elite detectives whose identities would not be revealed. They would report directly to him. And Petrosino would lead them.

Bingham never articulated how this “secret service” would be more successful than the Italian Squad, and his idea was met with skepticism in many circles. The new squad nonetheless came into being in early 1909, thanks to private donations.

Bingham’s main brainstorm, it appears, simply echoed what Petrosino had advocated for several years: to stop the flow of criminals from Italy by refusing entry to those with prison records. But getting the prison records was difficult, because the Italian government was not particularly forthcoming. Bingham asked Petrosino to travel to Italy and secure the judicial records.

It was a dangerous — perhaps foolhardy — endeavor. Petrosino was well known in Italy, even if he had not been there in decades. It would be difficult for him to operate without his enemies knowing who he was and what he was doing. It appears that Petrosino fully recognized the risks. Before he left, he signed over power of attorney to his wife, Adelina, so that if he died, she could collect his salary.

Petrosino’s secret mission began on February 9, 1909, when he boarded a steamship bound for Italy. However, his trip was hardly a secret. Later court testimony makes clear that the Mafia in New York were aware of his departure. In his first days in Italy, Petrosino was recognized by several people. And then Commissioner Bingham, for some inexplicable reason, publicly announced it. It’s not clear why, but Talty speculates that Bingham was known for provocative and regrettable public statements and simply made a tragic mistake. “Its recklessness is still almost incomprehensible,” Talty writes.

Petrosino’s enemies caught up with him in Sicily a little more than a month after he boarded the ship in New York. In hindsight, it seems almost inevitable that he would die on this mission. Questions remain unanswered to this day: Why did Petrosino travel to Italy rather than a more anonymous detective? Why didn’t he bring along a second man to guard his back? And why did he refuse offers of bodyguards from Italian officials?

Return to New York

The news of Petrosino’s death hit New York’s Little Italy hard. Petrosino’s NYPD colleagues mourned as well. Politicians and newspaper editorial writers called for harsher tactics to take down the Black Hand once and for all. But no one had a more painful reaction than the detective’s wife, Adelina, who received the news from a reporter. She was described as inconsolable.

When reporters told Teddy Roosevelt about Petrosino’s death, he took the time to deliver an eloquent and heartfelt comment. “Petrosino was a great man and a good man,” Roosevelt said. “I knew him for years and he did not know the name of fear. He was a man worth while. I regret most sincerely the death of such a man as Joe Petrosino.”

April 12, 1909, the day of Petrosino’s funeral, was declared a public holiday in New York. An estimated 250,000 people crowded the streets. “Never before in the history of New York or any other American city had such a crowd turned out for a man of the class to which Petrosino belonged, a humble police lieutenant,” Talty writes.

Petrosino was buried in Calvary Cemetery in Queens.

Who did it?

The investigation of Petrosino’s murder was led by Police Commissioner Baldassare Ceola. He and his officers interviewed witnesses, but no one would admit to having seen anything. Fear of Mafia reprisals dwarfed any desire to aid the investigation.

Still, police rounded up 140 suspects, including many Sicilians Petrosino had played a role in deporting from the United States. Although details were scant, Ceola soon came to believe the Petrosino killing was the work of the local Mafia, led by Vito Cascio Ferro. Cascio Ferro had crossed Petrosino back in New York years before, and he had a strong connection with Giuseppe Morello, who led the Mafia in New York. Morello, too, had reason to see Petrosino dead.

Anonymous letters sent to Ceola from the United States made the connection between Cascio Ferro and Morello, according to Mike Dash, author of The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder, and the Birth of the American Mafia. In addition, the letters claimed that the actual assassins were Carlo Costantino and Antonio Passananti. Ceola pieced together a plausible scenario showing that the Mafia leaders in New York and Palermo were behind Petrosino’s murder, but he could not muster enough evidence to take anyone to trial.

Petrosino today

Although not a household name, Petrosino is far from a forgotten historical figure. His name lives on in several ways, especially within the Italian American community in the New York area.

• Petrosino Park is located not far from New York’s Little Italy. It’s a small urban space, not heavily used, but with large signs at its entrance that explain the significance of the man for whom it is named.

• Petrosino’s boyhood home in Padula, Italy, has been turned into a museum.

• The Lt. Det. Joseph Petrosino Association in America, based in New York, was created to honor the legacy of Petrosino and to recognize individuals who make a difference in law enforcement, public service, government and business. It holds an annual dinner at which several individuals receive awards.

• The NYPD chapter of the Columbia Association, the fraternal organization for Italian American police officers, gives out an annual Lt. Joseph Petrosino Man of the Year award.

• The Sons of Italy lodge in New York’s Little Italy is officially known as Lt. Joseph Petrosino Lodge #285, honoring his name and badge number.

The Mob Museum recognizes Petrosino with a large portrait in its third-floor exhibition, but plans are in the works for a new exhibit with Petrosino’s story as the centerpiece.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org