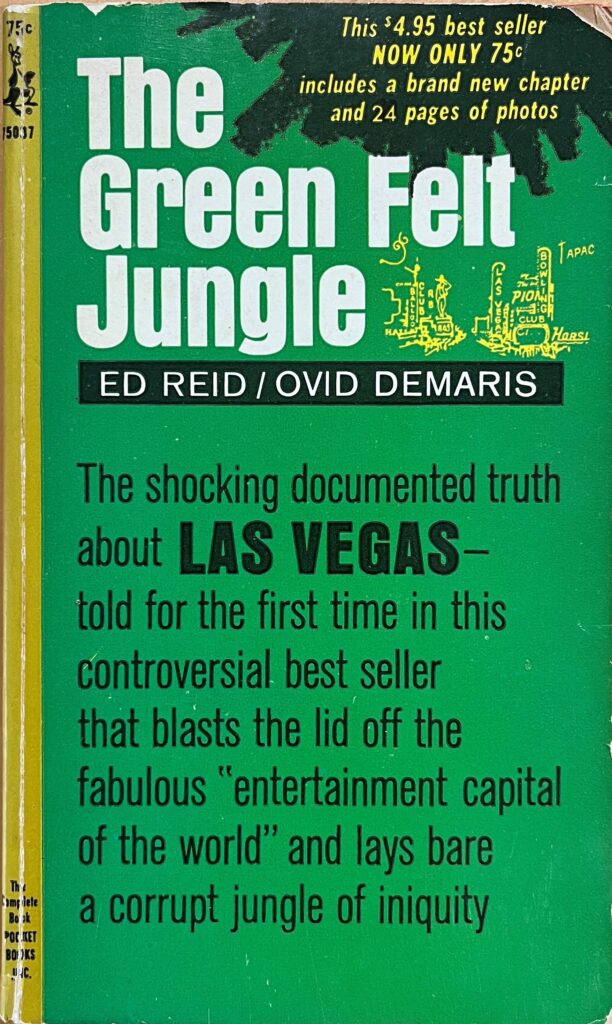

‘The Green Felt Jungle,’ published 60 years ago, rattled Las Vegas

Authors Ed Reid and Ovid Demaris exposed Mob influence in local casinos

When The Green Felt Jungle was published 60 years ago, the book created a stir by detailing Mob influence and public corruption in Las Vegas.

Some hailed the 1963 addition to organized crime history as a much-needed exposé, while critics regarded it as inflammatory and unfair.

Written by two crime reporters, Ed Reid and Ovid Demaris, The Green Felt Jungle was not the public’s first exposure to the Las Vegas underworld, but community boosters were put off by what they regarded as its harsh portrayal and insulting tone. The local business community viewed it as sensationalistic and harmful to economic development.

In the book, much of the focus is on shady casino operators, prostitution and corrupt public officials. The town itself is not spared. Las Vegas is described as a “grotesque” desert Disneyland “devoted to fleecing tourists.”

The appendix even created problems for some influential locals, with its list of casino owners and the percentages of their holdings as of April 1, 1962, including their mailing addresses. Some of those listed were mobsters or their associates. This faction was concerned the book would attract additional government scrutiny, jeopardizing the syndicate’s lucrative casino ventures in Las Vegas.

Mob attack at Desert Inn

Throughout the years, co-authors Reid and Demaris built respected careers writing newspaper articles and books about organized crime across the country. During this pre-internet era, their work relied upon source development and document research — and a journalist’s ability to hook readers with interesting details.

Earlier in his career, Reid had been a reporter at the Brooklyn Eagle, leading the newspaper to a 1951 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service by exposing an illegal gambling ring protected by corrupt police officers. His later article in True magazine, “I Broke the Brooklyn Graft Scandal,” resulted in the 1958 movie The Case Against Brooklyn.

After leaving the Eagle, Reid went to work for the Las Vegas Sun. While there, he was beaten during an encounter with mobsters at the Desert Inn, a now-demolished resort that stood on the east side of the resort corridor where Wynn Las Vegas is located today.

In a first-person account of the March 1954 incident for his former paper, the Brooklyn Eagle, the 39-year-old Reid said he’d gone to Las Vegas with the idea that it was the place to find “the most hoodlums concentrated in the smallest space.”

Las Vegas Sun Publisher Hank Greenspan had wanted Reid to produce a newspaper series about “syndicate hoodlums” in the city that had grown from a population of 8,000 to 50,000 in only a decade, the reporter noted. “I found so many hoodlums I could not begin to write about them all,” Reid wrote.

One article in the series especially seemed to strike a nerve. It mentioned Jack Dragna, a West Coast syndicate operative who, according to Reid, “dabbled in every form of crime for many years.”

As Reid put it, on a Saturday at 2 a.m. inside the Desert Inn, he saw about 10 “of the nation’s most notorious hoodlums” seated at tables flanking the craps tables and slot machines. At a nearby table was Clark County Sheriff Glen Jones. Dragna also was there.

As Reid stepped out of the resort’s glass entrance doors to leave, two men, including one who’d been seated with Dragna, beat him with their fists and a blackjack, Reid wrote. The attackers knocked off his glasses and left him bloodied.

Afterward, accounts of the incident varied, and a Clark County grand jury voted to take no action, according to a published report.

To Reid, however, the assault showed what the town was really like. “Maybe people will believe me now when I tell them Las Vegas is swarming with unsavory characters from all over the United States,” he said.

Top reporter fired

Though Reid had been the Las Vegas Sun’s ace reporter, publisher Hank Greenspun fired him after The Green Felt Jungle was released.

Years later, Greenspun’s son, Brian, now the Sun’s editor and owner, wrote in a column that The Green Felt Jungle zoomed to the top of the best-seller list as a nonfiction book but would have been “better nestled” in the fiction section.

Before the book went to print, Reid encouraged Hank Greenspun, his editor, to read the galleys.

“When my dad read what Ed Reid had written, he told him it was full of half-truths, innuendoes and lies and that Ed had to correct that which was wrong and misleading,” Brian Greenspun wrote. “Ed refused, and my father let him go.”

Hank Greenspun, who founded the Las Vegas Sun in 1950, had been employed a few years earlier by gangster Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel as a publicist at the Flamingo. A growth spurt in gaming during the following years attracted more tourists to the area, with a potential for even greater numbers. After The Green Felt Jungle came out, Greenspun looked for television and radio interview opportunities to explain what he regarded as the truth about Las Vegas.

Greenspun told his son Brian he did this because he wanted to do what he could to make sure “you are never ashamed of where you were born.”

Reid, who had written books before and after working at the Sun, including Las Vegas: City Without Clocks and The Grim Reapers, died in 1977.

For his part, Demaris also wrote other books, ranging from The Last Mafioso: The Treacherous World of Jimmy Fratianno to crime novels such as The Hoods Take Over and Candyleg. These two novels were made into movies — Gang War (1958), based on The Hoods Take Over, and Machine Gun McCain (1969), based on Candyleg.

In his novels, Demaris sometimes employed the themes and language found in the hard-boiled fiction of that era. One of his novels, The Lusting Drive, is included in a large volume for fans of gritty writing: Vintage Sleaze Super Pack: 24 Forbidden Novels from the 1950s and 1960s.

A former United Press International wire service reporter and author of more than 30 books, Demaris died in 1998.

Mob driven out of Las Vegas

Today’s Las Vegas Valley is different from the mobbed-up gambling outpost described 60 years ago in The Green Felt Jungle.

Since then, the area’s population has continued to grow and is expected to top 2.48 million in 2024, according to UNLV’s population forecast.

With this growth, mobsters like those that Reid and Demaris encountered have been pushed out. One important factor was the arrival in November 1966 of reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, who bought six casinos, most of them from the Mob. He lived in seclusion for a few years at the Desert Inn.

Also, the Nevada Legislature in 1967 authorized corporations to own and operate casinos, meaning each shareholder didn’t have to be investigated for suitability and licensed. According to the Nevada Resort Association, this “paved the way for the casino industry to become what it is today.”

Into the 1980s, aggressive local reporters such as Ned Day, Jeff German and Jane Ann Morrison focused attention on the mobsters still active in the valley. This focus, coupled with pressure from state regulators and law enforcement, put the Mob into a final tailspin by the mid-1980s.

In 1989, casino developer Steve Wynn opened the Mirage hotel-casino on the west side of the Las Vegas Strip, leading to a boom in megaresort construction. As a result, several formerly Mob-linked casinos were imploded. These included the Desert Inn, Sands, Riviera, Stardust, Dunes and Hacienda. In most instances, corporate megaresorts have replaced the demolished properties. The Flamingo, where Hank Greenspun once worked, is at the same location as when it first opened in December 1946, though none of the original buildings remains.

The region continues to evolve and now is positioning itself as the nation’s sports capital, with professional teams making their home on or near the Strip and major events such as the Formula One Las Vegas Grand Prix and the NFL’s 2024 Super Bowl occurring there.

One of the last Las Vegas Strip resorts with original construction from The Green Felt Jungle era, the Tropicana, is slated to be demolished so that a Major League Baseball stadium can be built at that site. The Oakland Athletics plan to relocate to Southern Nevada and begin playing home games at the stadium in 2028.

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. Today, he is a senior reporter for Gambling.com.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org